For other works with the same title, see Pelleas and Melisande (disambiguation).

| Claude Debussy |

|---|

|

Pelléas et Mélisande (Pelléas and Mélisande) is an opera in five acts with music by Claudio Debussy.

The French libretto was adapted from Maurice Maeterlinck's Symbolist play Pelléas et Mélisande.

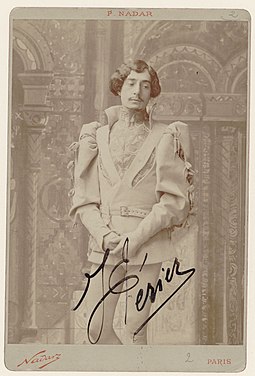

It premiered at the Opéra-Comique in Paris on 30 April 1902 with Jean Périer as Pelléas and Mary Garden as Mélisande in a performance conducted by André Messager, who was instrumental in getting the Opéra-Comique to stage the work.

The only opera Debussy ever completed, it is considered a landmark in 20th-century music.

The plot concerns a love triangle.

Prince Golaud finds a mysterious young woman, Melisanda, lost in a forest.

He marries her and brings her back to the castle of his grandfather, King Arkel of Allemonde.

Here Mélisande becomes increasingly attached to Golaud’s younger half-brother Pelléas, arousing Golaud’s jealousy.

Golaud goes to excessive lengths to find out the truth about Pelléas and Mélisande’s relationship, even forcing his own child, Yniold, to spy on the couple.

Pelléas decides to leave the castle but arranges to meet Mélisande one last time and the two finally confess their love for one another.

Golaud, who has been eavesdropping, rushes out and kills his half-brother Pelléas.

Mélisande dies shortly after (Golaud wounded her), having given birth to a daughter, with Golaud still begging her to tell him “the truth”.

"For a long time I had been striving to write music for the theatre, but the form in which I wanted it to be was so unusual that after several attempts I had given up on the idea."[1] There were many false starts before Pelléas et Mélisande. In the 1880s the young composer had toyed with several opera projects (Diane au Bois, Axël) before accepting a libretto on the theme of El Cid, entitled Rodrigue et Chimène, from the poet and Wagner aficionado Catulle Mendès.

At this point, Debussy too was a devotee of Wagner's music, but - eager to please his father - he was probably more swayed by Mendès' promise of a performance at the Paris Opéra and the money and reputation this would bring. Mendès' libretto, with its conventional plot, offered rather less encouragement to his creative abilities.[2] In the words of Victor Lederer, "Desperate to sink his teeth into a project of substance, the young composer accepted the type of old-fashioned libretto he dreaded, filled with howlers and lusty choruses of soldiers calling for wine."[3] Debussy's letters and conversations with friends reveal his increasing frustration with the Mendès libretto and the composer's enthusiasm for the Wagnerian aesthetic was also waning. In a letter of January 1892, he wrote, "My life is hardship and misery thanks to this opera. Everything about it is wrong for me." And to Paul Dukas, he confessed that Rodrigue was "totally at odds with all that I dream about, demanding a type of music that is alien to me."[4]

Debussy was already formulating a new conception of opera. In a letter to Ernest Guiraud in 1890 he wrote: "The ideal would be two associated dreams. No time, no place. No big scene [...] Music in opera is far too predominant. Too much singing and the musical settings are too cumbersome [...] My idea is of a short libretto with mobile scenes. No discussion or arguments between the characters whom I see at the mercy of life or destiny."[5] It was only when Debussy discovered the new Symbolist plays of Maurice Maeterlinck that he found a form of drama that answered his ideal requirements for a libretto.

Finding the right libretto[edit]

Maeterlinck's plays were tremendously popular with the avant-garde in the Paris of the 1890s. They were anti-naturalistic in content and style, forsaking external drama for a symbolic expression of the inner life of the characters.[6] Debussy had seen a production of Maeterlinck's first play La princesse Maleine and, in 1891, he applied for permission to set it but Maeterlinck had already promised it to Vincent d'Indy.[7]Debussy's interest shifted to Pelléas et Mélisande, which he had read some time between its publication in May 1892 and its first performance at the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens on 17 May 1893, a staging the composer attended.[8] Pelléas was a work that fascinated many other musicians of the time: both Gabriel Fauré and Jean Sibelius composed incidental music for the play, and Arnold Schoenberg was to write a tone poem on the theme. Debussy found in it the ideal opera libretto for which he had been searching.[9] In a 1902 article, "Pourquoi j’ai écrit Pelléas" (Why I wrote Pelléas), Debussy explained the appeal of the work:

"The drama of Pelléas which, despite its dream-like atmosphere, contains far more humanity than those so-called ‘real-life documents’, seemed to suit my intentions admirably. In it there is an evocative language whose sensitivity could be extended into music and into the orchestral backcloth."[8]Debussy abandoned work on Rodrigue and Chimène and, in August 1893, he approached Maeterlinck via his friend, the poet Henri de Régnier, for permission to set Pelléas. Maeterlinck was happy to grant it. Régnier claimed Debussy had already started work on the music but the evidence suggests that he did not begin composing the score until September.[10] In November, Debussy made a trip to Belgium, where he played excerpts from his work in progress to the famous violinist Eugène Ysaÿe in Brussels before visiting Maeterlinck at his home in Ghent. Debussy described the playwright as being initially as shy as a "girl meeting an eligible young man", but the two soon warmed to each other. Maeterlinck authorised Debussy to make whatever cuts in the play he wanted. He also admitted to the composer that he knew nothing about music.[11]

Composition[edit]

Debussy began work on Pelléas in September 1893. He decided to remove four scenes from the play (Act I Scene 1, Act II Scene 4, Act III Scene 1, Act V Scene 1[12]), significantly reducing the role of the serving-women to one silent appearance in the last act. He also cut back on the elaborate descriptions of which Maeterlinck was fond. Debussy's method of composition was fairly systematic; he worked on only one act at a time but not necessarily in chronological order. The first scene that he wrote was Act 4 Scene 4, the climactic love scene between Pelléas and Mélisande.[8]Debussy finished the short score of the opera (without detailed orchestration) on 17 August 1895. He did not go on to produce the full score needed for rehearsals until the Opéra-Comique accepted the work in 1898. At this point he added the full orchestration, finished the vocal score, and made several revisions. It is this version that went into rehearsals in January 1902.[8]

Putting Pelléas on stage[edit]

Finding a venue[edit]

Debussy spent years trying to find a suitable venue for the premiere of Pelléas et Mélisande, realising he would have difficulties getting such an innovative work staged. As he confided to his friend Camille Mauclair in 1895: "It is no slight work. I should like to find a place for it, but you know I am badly received everywhere." He also told Mauclair that he had contemplated asking the wealthy aesthete Robert de Montesquiou to have it performed at his Pavillon des Muses, but nothing came of this.[13]The composer and conductor André Messager was a great admirer of Debussy's music and had heard him play extracts from the opera. When Messager became chief conductor of the Opéra-Comique theatre in 1898, his enthusiastic recommendations prompted Albert Carré, the head of the opera house, to visit Debussy and hear the work played on the piano at two sessions, in May 1898 and April 1901. On the strength of this, Carré accepted the work for the Opéra-Comique and on 3 May 1901 gave Debussy a written promise to perform the opera the following season.[14]

Trouble with Maeterlinck[edit]

Maeterlinck first learned of Debussy's preference for Garden when an announcement appeared in Le ménestrel newspaper on 29 December 1901. He was furious and tried to take legal action to prevent the opera from going ahead. When this failed, he threatened Debussy with physical violence, telling Leblanc he was going to "give Debussy a drubbing to teach him what was what," and Madame Debussy had to dissuade him from attacking her husband with a cane. On 14 April, Le Figaro published a letter from Maeterlinck in which he completely dissociated himself from the production, complaining about the cuts that had been made in the libretto (although he had originally sanctioned them) and describing "the Pelléas in question" as "a work that is strange and hostile to me [...] I can only wish for its immediate and decided failure."[16] Maeterlinck finally saw the opera in 1920, two years after Debussy's death. He later confessed: "In this affair I was entirely wrong and he was a thousand times right."[17]

Rehearsals[edit]

Rehearsals for Pelléas et Mélisande began on 13 January 1902 and went on for 15 weeks; Debussy was present for 69 of the sessions.[18] Mélisande was not the only role which caused casting problems: the child who was to play Yniold was not chosen until 5 March. In the event, the boy (Blondin) proved incapable of singing the part competently and Yniold's main scene (Act IV Scene 3) was cut and only reinstated in later performances when the role was given to a woman. The rehearsals also showed that the stage machinery of the Opéra-Comique was unable to cope with the rapid set changes the libretto demanded and Debussy had to compose orchestral interludes to cover them.[19] Many of the orchestra and cast were hostile to Debussy's innovative work and, in the words of Roger Nichols, "may not have taken altogether kindly to the composer's injunction, reported by Mary Garden, to 'forget, please, that you are singers'." The dress rehearsal took place on the afternoon of Monday, 28 April and was a rowdy affair. Someone (in Mary Garden's view, Maurice Maeterlinck) distributed a salacious parody of the libretto to the audience, who also laughed at Garden's Scottish accent (she allegedly pronounced courage as curages, meaning "the dirt that gets stuck in drains").[20] The censor, Henri Roujon, asked Debussy to make a number of cuts before the premiere, including a mention of the word "bed". Debussy agreed but kept the libretto unaltered in the published score.[21]Premiere[edit]

Pelléas et Mélisande received its first performance at the Opéra-Comique in Paris on 30 April 1902 with André Messager conducting.

The sets were designed in the Pre-Raphaelite style by Lucien Jusseaume and Eugène Ronsin.[22]

The premiere received a warmer reception than the dress rehearsal because a group of Debussy aficionados counterbalanced the Opéra-Comique's regular subscribers, who found the work so objectionable.

Messager described the reaction: "[It was] certainly not a triumph, but no longer the disaster of two days before...From the second performance onwards, the public remained calm and above all curious to hear this work everyone was talking about...The little group of admirers, Conservatoire pupils and students for the most part, grew day by day..."[23]

Critical reaction was mixed.

Some accused the music of being "sickly and practically lifeless"[24] and of sounding "like the noise of a squeaky door or a piece of furniture being moved about, or a child crying in the distance."[25]

Camille Saint-Saëns, a relentless opponent of Debussy's music, claimed he had abandoned his customary summer holidays so he could stay in Paris and "say nasty things about Pelléas."[26]

But others — especially the younger generation of composers, students and aesthetes — were highly enthusiastic.

Debussy's friend Paul Dukas lauded the opera, Romain Rolland described it as "one of the three or four outstanding achievements in French musical history",[27] and Vincent d'Indy wrote an extensive review which compared the work to Wagner and early-17th-century Italian opera.

D'Indy found Pelléas moving, too:

"The composer has in fact simply felt and expressed the human feelings and human sufferings in human terms, despite the outward appearance the characters present of living in a dream."[28]

The opera won a "cult following" among young aesthetes, and the writer Jean Lorrain satirised the "Pelléastres" who aped the costumes and hairstyles of Mary Garden and the rest of the cast.[29]

Performance history[edit]

The initial run lasted for 14 performances, making a profit for the Opéra-Comique. It became a staple part in the repertory of the theatre, reaching its hundredth performance there on 25 January 1913.[30] In 1908, Maggie Teyte took over the role of Mélisande from Mary Garden. She described Debussy's reaction on learning her nationality: "Une autre anglaise—Mon Dieu" ("Another Englishwoman—my God"). Teyte also wrote about the composer's perfectionist character and his relations with the cast:As a teacher he was pedantic—that's the only word. Really pedantic [...] There was a core of anger and bitterness in him—I often think he was rather like Golaud in Pelléas and yet he wasn't. He was—it's in all his music—a very sensual man. No one seemed to like him. Jean Périer, who played Pelléas to my Mélisande, went white with anger if you mentioned the name of Debussy...[31]Debussy's perfectionism—plus his dislike of the attendant publicity—was one of the reasons why he rarely attended performances of Pelléas et Mélisande. However, he did supervise the first foreign production of the opera, which appeared at the Théâtre de la Monnaie, Brussels on 9 January 1907. This was followed by foreign premieres in Frankfurt on 19 April of the same year, New York at the Manhattan Opera House on 19 February 1908, and at La Scala, Milan with Arturo Toscanini conducting on 2 April 1908.[32] It first appeared in the United Kingdom at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden on 21 May 1909.[22]

In the years following World War I, the popularity of Pelléas et Mélisande began to fade somewhat. As Roger Nichols writes, "[The] two qualities of being escapist and easily caricatured meant that in the brittle, post-war Parisian climate Pelléas could be written off as no longer relevant."[33] The situation was the same abroad and in 1940 the English critic Edward J. Dent observed that "Pelléas et Mélisande seems to have fallen completely into oblivion." However, the Canadian premiere was given that same year at the Montreal Festivals under the baton of Wilfrid Pelletier.[34] Interest was further revived by the famous production which debuted at the Opéra-Comique on 22 May 1942 under the baton of Roger Désormière with Jacques Jansen and Irène Joachim in the title roles. The couple became "the Pelléas and Mélisande for a whole generation of opera-goers, last appearing together at the Opéra-Comique in 1955."[35]

Notable later productions include those with set designs by Jean Cocteau (first performed in Marseille in 1963), and the 1969 Covent Garden production conducted by Pierre Boulez. Boulez's rejection of the tradition of Pelléas conducting caused controversy among critics who accused him of "Wagnerising" Debussy, to which Boulez responded that the work was indeed heavily influenced by Wagner's Parsifal.[36] Boulez returned to conduct Pelléas in an acclaimed production by the German director Peter Stein for the Welsh National Opera in 1992. Modern productions have frequently re-imagined Maeterlinck’s setting, often moving the time period to the present day or other time period; for instance, the 1985 Opéra National de Lyon production set the opera during the Edwardian era.[8]

Roles[edit]

| Role | Voice type[37] | Premiere Cast, 30 April 1902 (Conductor: André Messager) |

|---|---|---|

| Arkel, King of Allemonde | bass | Félix Vieuille |

| Geneviève, mother of Golaud and Pelléas | contralto | Jeanne Gerville-Réache |

| Golaud grandson of Arkel | baritone or bass-baritone | Hector-Robert Dufranne |

| Pelléas, grandson of Arkel | tenor or high baritone (baryton-martin) | Jean Périer |

| Mélisande | soprano or high mezzo-soprano | Mary Garden |

| Yniold, the young son of Golaud | soprano or boy soprano | C Blondin |

| Doctor | bass | Viguié |

| Shepherd | baritone | |

| Offstage sailors (male chorus), serving women and three paupers (mute) | ||

Instrumentation[edit]

The score calls for:[22]- 3 flutes (one doubles piccolo), 2 oboes, cor anglais, 2 clarinets, 3 bassoons

- 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba

- timpani, cymbals, triangle, glockenspiel, bell

- 2 harps

- strings

Synopsis[edit]

Act 1[edit]

Scene 1: A forestPrince Golaud, grandson of King Arkel of Allemonde, has become lost while hunting in the forest.

Golaud discovers a frightened, weeping girl sitting by a spring in which a crown is visible.

She reveals her name is Mélisande but nothing else about her origins and refuses to let Golaud retrieve her crown from the water.

Golaud persuades her to come with him before the forest gets dark.

Scene 2: A room in the castle

Six months have passed.

Geneviève, the mother of the princes Golaud and Pelléas, reads a letter to the aged and nearly blind King Arkel.

It was sent by Golaud to his brother Pelléas.

In it Golaud reveals that he has married Mélisande, although he knows no more about her than on the day they first met.

Golaud fears that Arkel will be angry with him and tells Pelléas to find how he reacts to the news.

If the old man is favourable then Pelléas should light a lamp from the tower facing the sea on the third day.

If Golaud does not see the lamp shining, he will sail on and never return home.

Arkel had planned to marry the widowed Golaud to Princess Ursula in order to put an end to "long wars and ancient hatreds", but he bows to fate and accepts Golaud's marriage to Mélisande.

Pelléas enters, weeping.

He has received a letter from his friend Marcello, who is on his deathbed, and wants to travel to say goodbye to him.

Arkel thinks Pelléas should wait for the return of Golaud, and also reminds Pelléas of his own father, lying sick in bed in the castle.

Geneviève tells Pelléas not to forget to light the lamp for Golaud.

Scene 3: Before the castle

Geneviève and Mélisande walk in the castle grounds.

Mélisande remarks how dark the surrounding gardens and forest are.

Pelléas arrives.

They look out to sea and notice a large ship departing and a lighthouse shining, Mélisande foretells that it will sink.

Night falls.

Geneviève goes off to look after Yniold, Golaud's young son by his previous marriage.

Pelléas attempts to take Melisande's hand to help her down the steep path but she refuses saying that she is holding flowers.

He tells her he might have to go away tomorrow.

Mélisande asks him why.

Act 2[edit]

Scene 1: A well in the park

It is a hot summer day.

Pelléas has led Mélisande to one of his favourite spots, the "Blind Men's Well".

People used to believe it possessed miraculous powers to cure blindness but since the old king's eyesight started to fail, they no longer come there.

Mélisande lies down on the marble rim of the well and tries to see to the bottom.

Her hair loosens and falls into the water.

Pelléas notices how extraordinarily long it is.

He remembers that Golaud first met Mélisande beside a spring and asks if he tried to kiss her at that time but she does not answer.

Mélisande plays with the RING Golaud gave her, throwing it up into the air until it slips from her fingers into the well.

Pelléas tells her not to be concerned but she is not reassured.

He also notes that the clock was striking twelve as the ring dropped into the well.

Mélisande asks him what she should tell Golaud.

He replies, "the truth."

Scene 2: A room in the castle

Golaud is lying in bed with Mélisande at the bedside.

He is wounded, having fallen from his horse while hunting.

The horse suddenly bolted for no reason as the clock struck twelve.

Mélisande bursts into tears and says she feels ill and unhappy in the castle.

She wants to go away with Golaud.

He asks her the reason for her unhappiness but she refuses to say.

When he asks her if the problem is Pelléas, she replies that he is not the cause but she does not think he likes her.

Golaud tells her not to worry.

Pelléas can behave oddly and he is still very young.

Mélisande complains about the gloominess of the castle, today was the first time she saw the sky.

Golaud says that she is too old to be crying for such reasons and takes her hands to comfort her and notices the wedding ring is missing.

Golaud becomes furious, Mélisande claims (lying) she dropped it in a cave by the sea where she went to collect shells with little Yniold.

Golaud orders her to go and search for it at once before the tide comes in, even though night has fallen.

When Mélisande replies that she is afraid to go alone, Golaud tells her to take Pelléas along with her.

Scene 3: Before a cave

Pelléas and Mélisande make their way down to the cave in pitch darkness.

Mélisande is frightened to enter, but Pelléas tells her she will need to describe the place to Golaud to prove she has been there.

The moon comes out lighting the cave and reveals three beggars sleeping in the cave.

Pelléas explains there is a famine in the land.

He decides they should come back another day.

Act 3[edit]

Scene 1: One of the towers of the castle

Mélisande is at the tower window, singing a song (Mes longs cheveux) as she combs her hair.

Pelléas appears and asks her to lean out so he can kiss her hand as he is going away the next day.

He cannot reach her hand but her long hair tumbles down from the window and he kisses and caresses it instead.

Pelléas playfully ties Mélisande's hair to a willow tree in spite of her protests that someone might see them.

A flock of doves takes flight.

Mélisande panics when she hears Golaud's footsteps approaching.

Golaud dismisses Pelléas and Mélisande as nothing but a pair of children and leads Pelléas away.

Scene 2: The vaults of the castle

Golaud leads Pelléas down to the castle vaults, which contain the dungeons and a stagnant pool which has "the scent of death."

He tells Pelléas to lean over and look into the chasm while he holds him safely.

Pelléas finds the atmosphere stifling and they leave.

Scene 3: A terrace at the entrance of the vaults

Pelléas is relieved to breathe fresh air again.

It is noon.

He sees Geneviève and Mélisande at a window in the tower.

Golaud tells Pelléas that there must be no repeat of the "childish game" between him and Mélisande last night.

Mélisande is pregnant and the least shock might disturb her health.

It is not the first time he has noticed there might be something between Pelléas and Mélisande but Pelléas should avoid her as much as possible without making this look too obvious.

Scene 4: Before the castle

Golaud sits with his little son, Yniold, in the darkness before dawn and questions him about Pelléas and Mélisande.

The boy reveals little that Golaud wants to know since he is too innocent to understand what he is asking.

He says that Pelléas and Mélisande often quarrel about the door and that they have told Yniold he will one day be as big as his father.

Golaud is puzzled when learning that they (Pelléas and Mélisande) never send Yniold away because they are afraid when he is not there and keep on crying in the dark.

He admits that he once saw Pelléas and Mélisande kiss "when it was raining".

Golaud lifts his son on his shoulders to spy on Pelléas and Mélisande through the window but Yniold says that they are doing nothing other than looking at the light.

He threatens to scream unless Golaud lets him down again.

Golaud leads him away.

Act 4[edit]

Scene 1: A room in the castlePelléas tells Mélisande that his father is getting better and has asked him to leave on his travels.

He arranges a last meeting with Mélisande by the Blind Men's Well in the park.

Scene 2: The same

Arkel tells Mélisande how he felt sorry for her when she first came to the castle "with the strange, bewildered look of someone constantly awaiting a calamity."

But now that is going to change and Mélisande will "open the door to a new era that I foresee."

He asks her to kiss him.

Golaud bursts in with blood on his forehead — he claims it was caused by a thorn hedge.

When Mélisande tries to wipe the blood away, he angrily orders her not to touch him and demands his sword.

He says that another peasant has died of starvation.

Golaud notices Mélisande is trembling and tells her he is not going to kill her with the sword.

He mocks the "great innocence" Arkel says he sees in Mélisande's eyes.

He commands her to close them or "I will shut them for a long time."

He tells Mélisande that she disgusts him and drags her around the room by her hair.

When Golaud leaves, Arkel asks if he is drunk.

Mélisande simply replies that he does not love her any more.

Arkel comments: "If I were God, I would have pity on the hearts of men."

Scene 3: A well in the park

Yniold tries to lift a boulder to free his golden ball, which is trapped between it and some rocks.

As darkness falls, he hears a flock of sheep suddenly stop bleating.

A shepherd explains that they have turned onto a path that doesn't lead back to the sheepfold, but does not answer when Yniold asks where they will sleep.

Yniold goes off to find someone to talk to.

Scene 4: The same

Pelléas arrives alone at the well.

He is worried that he has become deeply involved with Mélisande and fears the consequences.

He knows he must leave but first, he wants to see Mélisande one last time and tell her things he has kept to himself.

Mélisande arrives.

She was able to slip out without Golaud's noticing.

At first she is distant but when Pelléas tells her he is going away she becomes more affectionate.

After admitting his love for her, Mélisande confesses that she has loved him since she first saw him.

Pelléas hears the servants shutting the castle gates for the night.

Now they are locked out, but Mélisande says that it is for the better.

Pelléas is resigned to fate too.

After the two kiss, Mélisande hears something moving in the shadows.

It is Golaud, who has been watching the couple from behind a tree.

Golaud strikes down a defenseless Pelléas with his sword and kills him.

Mélisande is also wounded but she flees into the woods saying to a dying Pelléas that she does not have courage.

Act 5[edit]

A bedroom in the castleMélisande sleeps in a sick bed after giving birth to her child.

The doctor assures Golaud that despite her wound, her condition is not serious.

Overcome with guilt, Golaud claims he has killed for no reason.

Pelléas and Mélisande merely kissed "like a brother and sister."

Mélisande wakes and asks for a window to be opened so she can see the sunset.

Golaud asks the doctor and Arkel to leave the room so he can speak with Mélisande alone.

He blames himself for everything and begs Melisande's forgiveness.

Golaud presses Mélisande to confess her forbidden love for Pelléas.

She maintains her innocence in spite of Golaud's increasingly desperate pleas to her to tell the truth.

Arkel and the doctor return.

Arkel tells Golaud to stop before he kills Mélisande, but he replies "I have already killed her."

Arkel hands Mélisande her newborn baby girl but she is too weak to lift the child in her arms and remarks that the baby does not cry and that she will live a sad existence.

The room fills with serving women, although no one can tell who has summoned them.

Mélisande quietly dies.

At the moment of death, the serving women fall to their knees.

Arkel comforts the sobbing Golaud.[38]

Character of the work[edit]

An innovative libretto[edit]

Rather than engaging a librettist to adapt the original play for him (as was customary), Debussy chose to set the text directly, making only a number of cuts.Maeterlinck's play was in prose rather than verse.

Russian composers, notably Mussorgsky (whom Debussy admired), had experimented with setting prose opera libretti in the 1860s, but this was highly unusual in France (or Italy or Germany).

Debussy's example influenced many later composers who edited their own libretti from existing prose plays, e.g. Richard Strauss' Salome, Alban Berg's Wozzeck and Bernd Alois Zimmermann's Die Soldaten.[39]

The nature of the libretto Debussy chose to set contributes to the most famous feature of the opera: the almost complete absence of arias or set pieces.

There are only two reasonably lengthy passages for soloists:

Geneviève's reading of the letter in Act One and Mélisande's song from the tower in Act 3 (which would probably have been set to music in a spoken performance of Maeterlinck's play in any case).[40]

Instead, Debussy set the text one note to a syllable in a "continuous, fluid 'cantilena', somewhere between chant and recitative".[41]

Debussy, Wagner and French tradition[edit]

Pelléas reveals Debussy's deeply ambivalent attitude to the works of the German composer Richard Wagner.As Donald Grout writes: "it is customary, and in the main correct, to regard Pelléas et Mélisande as a monument to French operatic reaction to Wagner".[42]

Wagner had revolutionised 19th-century opera by his insistence on making his stage works more dramatic, by his increased use of the orchestra, his abolition of the traditional distinction between aria and recitative in favour of what he termed "endless melody", and by his use of leitmotifs, recurring musical themes associated with characters or ideas.

Wagner was a highly controversial figure in France. Despised by the conservative musical establishment, he was a cult figure in "avant-garde" circles, particularly among literary groups such as the Symbolists, who saw parallels between Wagner's concept of the leitmotif and their use of the symbol.

The young Debussy joined in this enthusiasm for Wagner's music, making a pilgrimage to the Bayreuth Festival in 1888 to see Parsifal and Die Meistersinger and returning in 1889 to see Tristan und Isolde. Yet that same year he confessed to his friend Ernest Guiraud his need to escape Wagner's influence.[43]

Debussy was well aware of the dangers of imitating Wagner too closely.

Several French composers had tried to write their own Wagnerian music dramas, including Emmanuel Chabrier (Gwendoline) and Ernest Chausson (Le roi Arthus). Debussy was far from impressed by the results:

"We are bound to admit that nothing was ever more dreary than the neo-Wagnerian school in which the French genius had lost its way among the sham Wotans in Hessian boots and the Tristans in velvet jackets."[44]

Debussy strove to avoid excessive Wagnerian influence on Pelléas from the start.

The love scene was the first music he composed but he scrapped his early drafts for being too conventional and because "worst of all, the ghost of old Klingsor,[45] alias R.Wagner, kept appearing."[46]

However, Debussy took several features from Wagner, including the use of leitmotifs, though these are "rather the 'idea-leitmotifs' of the more mature Wagner of Tristan than the 'character-leitmotifs' of his earlier music-dramas."[47]

Debussy referred to what he felt were Wagner's more obvious leitmotifs as a "box of tricks" (boîte à trucs) and claimed there was "no guiding thread in Pelléás" as "the characters are not subjected to the slavery of the leitmotif."[48]

Yet, as Debussy admitted privately, there are themes associated with each of the three main characters in Pelléas.

The continuous use of the orchestra is another feature of Wagnerian music drama, yet the way Debussy writes for the orchestra is completely different from Tristan, for example.

In Grout's words,

"In most places the music is no more than an iridescent veil covering the text."[49]

The emphasis is on quietness, subtlety and allowing the words of the libretto to be heard.

There are only four fortissimos in the entire score.

Debussy's use of declamation is un-Wagnerian as he felt Wagnerian melody was unsuited to the French language.

Instead, he stays close to the rhythms of natural speech, making Pelléas part of a tradition which goes back to the French Baroque tragédies en musique of Rameau and Lully as well as the experiments of the very founders of opera, Peri and Caccini.[49]

Like Tristan the subject of Pelléas is a love triangle set in a vaguely Medieval world.

Unlike the protagonists of Tristan, the characters rarely seem to understand or be able to articulate their own feelings.[50]

The deliberate vagueness of the story is paralleled by the elusiveness of Debussy's music.

Use of language[edit]

In both Debussy and Maeterlinck's view, the vagueness of the story is also expressed in the use of the language, which is usually lost in translation from French into English, since the characters switch back and forth between the formal "vous" and the familiar "toi", which is used to somewhat express how the characters are thinking, for instance, Mélisande always speaks to Golaud in the formal "vous" and when wanting to keep Pelléas to a distance, she uses that same form of speech, but when being more affectionate, she uses the familiar "toi".Aftermath[edit]

Pelléas was to be Debussy's only completed opera.For this reason it has sometimes been compared to Beethoven's Fidelio.

As Hugh Macdonald writes: "Both operas were much-loved only children of doting creators who put so much into their making that there could be no second child to follow after."[51] This was not for want of trying on Debussy's part, and he worked hard to create a successor.

Details of several opera projects survive.

The most substantial surviving musical sketches are for two works based on short stories by Edgar Allan Poe: Le diable dans le beffroi and La chute de la maison Usher.[22]

Debussy also planned a version of Shakespeare's As You Like It with a libretto by Paul-Jean Toulet, but the poet's opium addiction meant he was too lazy to write the text.[52] Two other projects suggest Debussy intended to challenge German composers on their own ground. Orphée-Roi (King Orpheus) was to be a riposte to Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice, which Debussy considered to "treat only the anecdotal, lachrymose aspect of the subject.".[53]

But, according to Victor Lederer, for "shock value, neither [As You Like It nor Orphée] tops the Tristan project of 1907 [...] According to Léon Vallas, one of Debussy's early biographers, its 'episodic character... would have been related to the tales of chivalry, and diametrically opposed to the Germanic conception of Wagner.' That Debussy entertained, if only for a few weeks, the idea of writing an opera based on the Tristan legend is quite incredible.

He knew Wagner's colossal Tristan und Isolde as well as anyone, and his confidence must have been great indeed if he felt up to treating the subject."[54]

However, nothing came of any of these schemes, partly because the rectal cancer which afflicted Debussy from 1909 meant that he found it increasingly hard to concentrate on sustained creative work. Pelléas would remain a unique opera.[22]

Marius Constant wrote a 20-minute "Symphonie" based on the opera.[55]

Recordings[edit]

Main article: Pelléas et Mélisande discography

The earliest recording of Pelléas et Mélisande is a 1904 Edison cylinder recording of Mary Garden singing the passage "Mes longs cheveux", with Debussy accompanying her on the piano.[56] The first complete recording of the opera was made by the Grand Orchestre Symphonique du Grammophone under conductor Piero Coppola in 1927. The 1942 recording conducted by Roger Désormière, is considered a reference by most critics.References[edit]

Notes- Jump up ^ Quoted in The Cambridge Opera Handbook p.31

- Jump up ^ Claude Samuel, booklet notes to Kent Nagano's recording of Rodrigue et Chimène (Erato Records, 1995) p. 12

- Jump up ^ Victor Lederer p.42

- Jump up ^ Claude Samuel pp.12-13

- Jump up ^ Quoted in Viking, p.247

- Jump up ^ The Reader's Encyclopedia, ed. Benet (1967 edition) p.618

- Jump up ^ Cambridge Opera Handbook p.30

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Richard Langham Smith: "Pelléas et Mélisande", Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed January 21, 2009), (subscription access)

- Jump up ^ Holmes p.42

- Jump up ^ Cambridge Handbook p.33

- Jump up ^ Holmes p.44

- Jump up ^ Cambridge Handbook p.34

- Jump up ^ Holmes p.51

- Jump up ^ Nichols in Cambridge Opera Handbook p.141

- Jump up ^ Holmes p.63

- Jump up ^ Holmes p.62

- Jump up ^ Booklet notes by Chimènes, p.51. Maeterlinck's original French: "...dans cette affaire j'avais entièrement tort et lui, mille fois raison."

- Jump up ^ Nichols Life p.104

- Jump up ^ Cambridge Companion to Debussy p.79

- Jump up ^ Nichols in Cambridge Opera Handbook p.143–7

- Jump up ^ Cambridge Companion to Debussy p.80

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Viking p.248

- Jump up ^ Nichols and Langham Smith (1989) p.147

- Jump up ^ Nichols Life p.106

- Jump up ^ Holmes p.65

- Jump up ^ Cambridge Opera Handbook p.148

- Jump up ^ Holmes p.66

- Jump up ^ Cambridge Opera Handbook, p.149

- Jump up ^ Holmes pp. 66–67

- Jump up ^ Cambridge Opera Handbook p.150

- Jump up ^ Holmes p.83

- Jump up ^ Cambridge Opera Handbook p.151

- Jump up ^ Cambridge Opera Handbook p.154

- Jump up ^ Wilfrid Pelletier at thecanadianencyclopedia.com

- Jump up ^ Cambridge Opera Handbook pp. 156–9

- Jump up ^ Cambridge Opera Handbook pp.&nsbp;164–5

- Jump up ^ The opera is unusual in that each of the main roles can be sung by a wide range of voice types. For instance, soprano Victoria de los Ángeles and mezzo-soprano Frederica von Stade have both sung the role of Mélisande; and tenor Nicolai Gedda, and such lyric baritones as Thomas Allen, Simon Keenlyside and Rod Gilfry have sung Pelléas.

- Jump up ^ Translations of Maeterlinck's words from the libretto included in the Abbado recording on Decca

- Jump up ^ Maehder in the booklet to Abbado's recording, p.27

- Jump up ^ Griffiths p.282

- Jump up ^ Viking Opera Guide p.249

- Jump up ^ Grout p.581

- Jump up ^ Bellingardi in the booklet to Abbado p.58ff

- Jump up ^ Quoted by Holmes p.67

- Jump up ^ The evil magician in Wagner's Parsifal

- Jump up ^ Cambridge Companion p.74

- Jump up ^ Cambridge Handbook p.79

- Jump up ^ Cambridge p.81

- ^ Jump up to: a b Grout p.582

- Jump up ^ Griffiths

- Jump up ^ Macdonald p.11

- Jump up ^ Holmes p.68

- Jump up ^ Léon Vallas Claude Debussy: His Life and Works p.219

- Jump up ^ Victor Lederer Debussy: The Quiet Revolutionary p.42

- Jump up ^ Presto Classical

- Jump up ^ Penguin Guide to Opera on Compact Discs ed. Greenfield, March and Layton (1993) p.68

- Amadeus Almanac, accessed 2 November 2008

- Holden, Amanda (Ed.), The New Penguin Opera Guide, New York: Penguin Putnam, 2001. ISBN 0-14-029312-4

- Holmes, Paul, Debussy (Omnibus, 1991) ISBN 0-7119-1752-3

- MacDonald, Hugh (in English), Booklet notes to the 1992 Deutsche Grammophon recording of Pelléas et Mélisande (conducted by Claudio Abbado). Others by Jürgen Maehder and Annette Kreutziger-Herr (in German), and Myriam Chimènes (in French)

- Nichols, Roger and Richard Langham Smith (eds.) Claude Debussy: Pelléas et Mélisande (Cambridge Opera Handbooks, Cambridge University Press, 1989) ISBN 0-521-31446-1

- Nichols, Roger, The Life of Debussy (Cambridge University Press, 2008) ISBN 0-521-57887-6

- Orledge, Robert, Debussy and the Theatre (Cambridge University Press, 1982) ISBN 0-521-22807-7

- Tresize, Simon, (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Debussy (Cambridge University Press, 2003) ISBN 0-521-65478-5

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pelléas et Mélisande (opera). |

- Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande: A Guide to the Opera with Musical Examples from the Score at Project Gutenberg, a contemporaneous analysis

- Full Piano Score with notes

- Pelléas et Mélisande: Free scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Synopsis

| ||

| ||

| ||

No comments:

Post a Comment