Gladiatorial "shows" in Ancient Rome turn war into a "game".

They reserved an atmosphere of violence in time of peace.

They functioned as a political theatre which allowed confrontation between rulers and ruled.

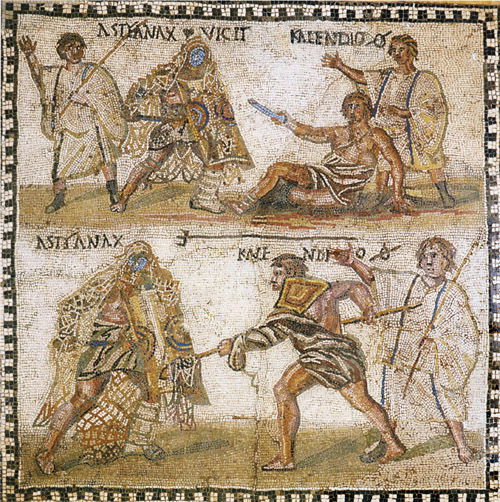

Mosaic showing a "retiario" (net-fighter) named Kalendio fighting a "secutor" named Astyanax

Mosaic showing a "retiario" (net-fighter) named Kalendio fighting a "secutor" named AstyanaxAfter the defeat of Cartago in 201 BC, Roma embarked on two centuries of almost continuous imperial expansion.

By the end of this period, Rome controls the whole of the Mediterranean basin and much of north-western Europe.

The population of her empire, at between 50 and 60 million people, constituted perhaps one-fifth or one-sixth of the world's then population.

Victorious conquest had been bought at a huge price, measured in human suffering, carnage, and money.

The costs were borne by tens of thousands of conquered peoples, who paid taxes to the Roman state, by slaves captured in war and transported to Italy, and by Roman soldiers who served long years fighting overseas.

The discipline of the Roman army was notorious.

"Decimation" is one index of its severity.

If an army unit was judged disobedient or cowardly in battle, one soldier in ten was selected by lot and cudgelled to death by his "comrades".

It should be stressed that "decimation" was not just a myth told to terrify fresh recruits.

It actually happens in the period of imperial expansion, and frequently enough not to arouse particular comment.

Roman soldiers killed each other for their common good.

When Romans were so unmerciful to each other, what mercy could prisoners of war expect?

Small wonder then that they were sometimes forced to fight in GLADIATORIAL contests, or were thrown to wild beasts for popular entertainment.

Public executions helped inculcate valour and fear in the men, women and children left at home.

Children learnt the lesson of what happened to soldiers who were defeated.

Public executions are in Ancient Roma rituals which help maintain an atmosphere of violence, even in times of peace.

Bloodshed and slaughter joined military glory and conquest as central elements in Roman culture.

With the accession of the first emperor Augusto (31 BC – AD 14), the Roman state embarked on a period of long-term peace (pax romana).

For more than two centuries, thanks to its effective defence by frontier armies, the inner core of the Roman empire was virtually insulated from the direct experience of war.

Then in memory of their warrior traditions, the Romans set up artificia1 battle-fields in cities and towns for public amusement.

The custom spread from Italy to the provinces.

Nowadays, we admire the Colosseo in Rome and other great Roman amphi-theatres such as those at Verona, Arles, Nimes and El Djem as architectural monuments.

We choose to forget that this was where Romans regularly organised fights to the death between hundreds of gladiators, the mass execution of unarmed criminals, and the indiscriminate slaughter of domestic and wild animals.

The enormous size of the amphi-theatres indicates how popular these exhibitions were.

The Colosseo was dedicated in AD 80 with 100 days of games.

One day 3,000 men fought.

On another 9,000 animals were killed.

It seated 50,000 people.

It is still one of Rome's most impressive buildings, a magnificent feat of engineering and design.

In ancient times, amphi-theatres must have towered over cities, much as cathedrals towered over medieval towns.

Public killings of men and animals are an Ancient Roman rite, with overtones of religious sacrifice, legitimated by the myth that gladiatorial shows inspired the populace with a glory in wounds and a contempt of death.

Philosophers, and later Christians, disapproved strongly.

To little effect.

Gladiatorial games persisted at least until the early fifth century AD, wild-beast killings until the sixth century.

St Augustine in his Confessions tells the story of a Christian who was reluctantly forced along to the amphitheatre by a party of friends.

At first, he kept his eyes shut, but when he heard the crowd roar, he opened them, and became converted by the sight of blood into an eager devotee of gladiatorial shows.

Even the biting criticism quoted below reveals a certain excitement beneath its moral outrage.

Seneca, Roman senator and philosopher, tells of a visit he once paid to the arena.

Seneca arrived in the middle of the day, during the mass execution of criminals, staged as an entertainment in the interval between the wild-beast show in the morning and the gladiatorial show of the afternoon.

All the previous fighting had been merciful by comparison.

Now finesse is set aside, and we have pure unadulterated murder.

The combatants have no protective covering.

Their entire bodies are exposed to the blows.

No blow falls in vain.

This is what lots of people prefer to the regular contests, and even to those which are put on by popular request.

And it is obvious why.

There is no helmet, no shield to repel the blade.

Why have armour?

Why bother with skill?

All that just delays death.

In the morning, men are thrown to lions and bears.

At mid-day they are thrown to the spectators themselves.

No sooner has a man killed, than they shout for him to kill another, or to be killed.

The final victor is kept for some other slaughter.

In the end, every fighter dies.

And all this goes on while the arena is half empty.

You may object that the victims committed robbery or were murderers.

So what?

Even if they deserved to suffer, what's your compulsion to watch their sufferings?

Kill him', they shout, 'Beat him, burn him'.

Why is he too timid to fight?

Why is he so frightened to kill?

Why so reluctant to die?

They have to whip him to make him accept his wounds.

Much of our evidence suggests that gladiatorial contests were, by origin, closely connected with funerals.

Once upon a time, wrote Tertullian, men believed that the souls of the dead were propitiated by human blood, and so at funerals they sacrificed prisoners of war or slaves of poor quality bought for the purpose.

The First Gladiators.

The first recorded gladiatorial show took place in 264 BC.

It was presented by two NOBLES in honour of their dead father.

Only three pairs of gladiators took part.

Over the next two centuries, the scale and frequency of gladiatorial shows increased steadily.

In 65 BC, for example, Giulio Cesare gave elaborate funeral games for his father involving 640 gladiators and condemned criminals who were forced to fight with wild beasts.

At his next games in 46 BC, in memory of his dead daughter and, let it be said, in celebration of his recent triumphs in Gaul and Egypt, Caesar presented not only the customary fights between individual gladiators, but also fights between whole detachments of infantry and between squadrons of cavalry, some mounted on horses, others on elephants.

Large-scale gladiatorial shows had arrived.

Some of the contestants were professional gladiators, others prisoners of war, and others criminals condemned to death.

Up to this time, gladiatorial shows had always been put on by individual aristocrats at their own initiative and expense, in honour of dead relatives.

The religious component in gladiatorial ceremonies continued to be important.

For example, attendants in the arena were dressed up as gods.

Slaves who tested whether fallen gladiators were really dead or just pretending, by applying a red-hot cauterising iron, were dressed as the god Mercurio.

Those who dragged away the dead bodies were dressed as Plutone, the god of the underworld.

During the persecutions of Christians, the victims were sometimes led around the arena in a procession dressed up as priests and priestesses of pagan cults, before being stripped naked and thrown to the wild beasts.

The welter of blood in gladiatorial and wild-beast shows, the squeals and smell of the human victims and of slaughtered animals are completely alien to us and almost unimaginable.

For some Romans they must have been reminiscent of battlefields, and, more immediately for everyone, associated with religious sacrifice.

At one remove, Romans, even at the height of their civilisation, performed human sacrifice, purportedly in commemoration of their dead.

By the end of the last century BC, the religious and commemorative elements in gladiatorial shows are eclipsed by the political and the spectacular.

Gladiatorial shows were public performances held mostly, before the amphitheatre was built, in the ritual and social centre of the city, the Forum.

Public participation, attracted by the splendour of the show and by distributions of meat, and by betting, magnified the respect paid to the dead and the honour of the whole family.

Aristocratic funerals in the Republic (before 31 BC) were political acts.

And funeral games had political implications, because of their popularity with citizen electors.

Indeed, the growth in the splendour of gladiatorial shows was largely fuelled by competition between ambitious aristocrats, who wished to please, excite and increase the number of their supporters.

In 42 BC, for the first time, gladiatorial fights were substituted for chariot-races in official games.

After that in the city of Rome, regular gladiatorial shows, like theatrical shows and chariot-races, were given by officers of state, as part of their official careers, as an official obligation and as a tax on status.

The Emperor Augusto, as part of a general policy of limiting aristocrats' opportunities to court favour with the Roman populace, severely restricted the number of regular gladiatorial shows to two each year.

He also restricts their splendour and size.

Each official was forbidden to spend more on them than his colleagues, and an upper limit was fixed at 120 gladiators a show.

These regulations were gradually evaded.

The pressure for evasion was simply that, even under the emperors, aristocrats were still competing with each other, in prestige and political success.

The splendour of a senator's public exhibition could make or break his social and political reputation.

One aristocrat, Simmaco, wrote to a friend thus.

I must now outdo the reputation earned by my own shows.

Our family's recent generosity during my consulship and the official games given for my son allow us to present nothing mediocre'.

So he set about enlisting the help of various powerful friends in the provinces.

In the end, he managed to procure antelopes, gazelles, leopards, lions, bears, bear-cubs, and even some crocodiles, which only just survived to the beginning of the games, because for the previous fifty days they had refused to eat.

Moreover, 29 Saxon prisoners of war strangled each other in their cells on the night before their final scheduled appearance.

Simmaco was heart-broken.

Like every donor of the games, he knew that his political standing was at stake.

Every presentation was in Goffman's strikingly apposite phrase 'a status bloodbath'.

The most spectacular gladiatorial shows were given by the emperors themselves at Rome.

For example, the Emperor Trajan, to celebrate his conquest of Dacia (roughly modern Roumania), gave games in AD 108-9 lasting 123 days in which 9,138 gladiators fought and eleven thousand animals were slain.

The Emperor Claudio in AD 52 presided in full military regalia over a battle on a lake near Rome between two naval squadrons, manned for the occasion by 19,000 forced combatants.

The palace guard, stationed behind stout barricades, which also prevented the combatants from escaping, bombarded the ships with missiles from catapaults.

After a faltering start, because the men refused to fight, the battle according to Tacitus 'was fought with the spirit of free men, although between criminals.

After much bloodshed, those who survived were spared extermination.

The quality of Roman justice was often tempered by the need to satisfy the demand for the condemned.

Christians, burnt to death as scape-goats after the great fire at Rome in AD 64, were not alone in being sacrificed for public entertainment.

Slaves and bystanders, even the spectators themselves, ran the risk of becoming victims of emperors' truculent whims.

The Emperor Claudius, for example, dissatisfied with how the stage machinery worked, ordered the stage mechanics responsible to fight in the arena.

One day, when there was a shortage of condemned criminals, the Emperor Caligula commanded that a whole section of the crowd be seized and thrown to the wild beasts instead.

Isolated incidents, but enough to intensify the excitement of those who attended.

Imperial legitimacy was reinforced by terror.

As for animals, their sheer variety symbolised the extent of Roman power and left vivid traces in Roman art.

In 169 BC, sixty-three African lions and leopards, forty bears and several elephants were hunted down in a single show.

New species were gradually introduced to Roman spectators (tigers, crocodiles, giraffes, lynxes, rhinoceros, ostriches, hippopotami) and killed for their pleasure.

Not for Romans the tame viewing of caged animals in a zoo.

Wild beasts were set to tear criminals to pieces as public lesson in pain and death.

Sometimes, elaborate sets and theatrical backdrops were prepared in which, as a climax, a criminal was devoured limb by limb.

Such spectacular punishments, common enough in pre-industrial states, helped reconstitute sovereign power.

The deviant criminal was punished.

Law and order were re-established.

The labour and organisation required to capture so many animals and to deliver them alive to Rome must have been enormous.

Even if wild animals were more plentiful then than now, single shows with one hundred, four hundred or six hundred lions, plus other animals, seem amazing.

By contrast, after Roman times, no hippopotamus was seen in Europe until one was brought to London by steamship in 1850.

It took a whole regiment of Egyptian soldiers to capture it, and involved a five month journey to bring it from the White Nile to Cairo.

And yet the Emperor Commodo, a dead-shot with spear and bow, himself killed five hippos, two elephants, a rhinoceros and a giraffe, in one show lasting two days.

On another occasion he killed 100 lions and bears in a single morning show, from safe walkways specially constructed across the arena.

It was, a contemporary remarked, a better demonstration of accuracy than of courage.

The slaughter of exotic animals in the emperor's presence, and exceptionally by the emperor himself or by his palace guards, was a spectacular dramatisation of the emperor's formidable power: immediate, bloody and symbolic.

Gladiatorial shows also provide in Ancient Rome an arena for popular participation in politics.

Cicerone explicitly recognised this towards the end of the Republic.

The judgement and wishes of the Roman people about public affairs can be most clearly expressed in three places: public assemblies, elections, and at plays or gladiatorial shows.

He challenged a political opponent.

Give yourself to the people.

Entrust yourself to the Games.

Are you terrified of not being applauded?

His comments underline the fact that the crowd had the important option of giving or of withholding applause, of hissing or of being silent.

Under the emperors, as citizens' rights to engage in politics diminished, gladiatorial shows and games provided repeated opportunities for the dramatic confrontation of rulers and ruled.

Rome was unique among large historical empires in allowing, indeed in expecting, these regular meetings between emperors and the massed populace of the capital, collected together in a single crowd.

To be sure, emperors could mostly stage-manage their own appearance and reception.

They gave extravagant shows.

They threw gifts to the crowd – small marked wooden balls (called missilia ) which could be exchanged for various luxuries.

They occasionally planted their own claques in the crowd.

Mostly, emperors received standing ovations and ritual acclamations.

The Games at Rome provided a stage for the emperor to display his majesty – luxurious ostentation in procession, accessibility to humble petitioners, generosity to the crowd, human involvement in the contests themselves, graciousness or arrogance towards the assembled aristocrats, clemency or cruelty to the vanquished.

When a gladiator fell, the crowd would shout for mercy or dispatch.

The emperor might be swayed by their shouts or gestures, but he alone, the final arbiter, decided who was to live or die.

When the emperor entered the amphitheatre, or decided the fate of a fallen gladiator by the movement of his thumb, at that moment he had 50,000 courtiers.

He knew that he was Caesar Imperator , Foremost of Men.

Things did not always go the way the emperor wanted.

Sometimes, the crowd objected, for example to the high price of wheat, or demanded the execution of an unpopular official or a reduction in taxes.

Caligula once reacted angrily and sent soldiers into the crowd with orders to execute summarily anyone seen shouting.

Understandably, the crowd grew silent, though sullen.

But the emperor's increased unpopularity encouraged his assassins to act.

Dio, senator and historian, was present at another popular demonstration in the Circus in AD 195.

He was amazed that the huge crowd (the Circus held up to 200,000 people) strung out along the track, shouted for an end to civil war like a well-trained choir.

Dio also recounted how with his own eyes he saw the Emperor Commodus cut off the head of an ostrich as a sacrifice in the arena then walk towards the congregated senators whom he hated, with the sacrificial knife in one hand and the severed head of the bird in the other, clearly indicating, so Dio thought, that it was the senators' necks which he really wanted.

Years later, Dio recalled how he had kept himself from laughing (out of anxiety, presumably) by chewing desperately on a laurel leaf which he plucked from the garland on his head.

Consider how the spectators in the amphitheatre sat.

The emperor in his gilded box, surrounded by his family; senators and knights each had special seats and came properly dressed in their distinctive purple-bordered togas.

Soldiers were separated from civilians.

Even ordinary citizens had to wear the heavy white woollen toga, the formal dress of a Roman citizen, and sandals, if they wanted to sit in the bottom two main tiers of seats.

Married men sat separately from bachelors, boys sat in a separate block, with their teachers in the next block.

Women, and the very poorest men dressed in the drab grey cloth associated with mourning, could sit or stand only in the top tier of the amphitheatre.

Priests and Vestal Virgins (honorary men) had reserved seats at the front.

The correct dress and segregation of ranks underlined the formal ritual elements in the occasion, just as the steeply banked seats reflected the steep stratification of Roman society.

It mattered where you sat, and where you were seen to be sitting.

Gladiatorial shows were political theatre.

The dramatic performance took place, not only in the arena, but between different sections of the audience.

Their interaction should be included in any thorough account of the Roman constitution.

The amphitheatre was the Roman crowd's parliament.

Games are usually omitted from political histories, simply because in our own society, mass spectator sports count as leisure.

But the Romans themselves realised that metropolitan control involved bread and circuses'.

The Roman people', wrote Marcus Aurelius' tutor Fronto, 'is held together by two forces: wheat doles and public shows'.

Enthusiastic interest in gladiatorial shows occasionally spilled over into a desire to perform in the arena.

Two emperors were not content to be spectators-in-chief.

They wanted to be prize performers as well.

Nerone's histrionic ambitions and success as musician and actor were notorious.

He also prided himself on his abilities as a charioteer.

Commodus performed as a gladiator in the amphitheatre, though admittedly only in preliminary bouts with blunted weapons.

He won all his fights and charged the imperial treasury a million sesterces for each appearance (enough to feed a thousand families for a year).

Eventually, he was assassinated when he was planning to be inaugurated as consul (in AD 193), dressed as a gladiator.

Commodus' gladiatorial exploits were an idiosyncratic expression of a culture obsessed with fighting, bloodshed, ostentation and competition.

But at least seven other emperors practised as gladiators, and fought in gladiatorial contests.

And so did Roman senators and knights.

Attempts were made to stop them by law.

But the laws were evaded.

Roman writers tried to explain away these senators' and knights' outrageous behaviour by calling them morally degenerate, forced into the arena by wicked emperors or their own profligacy.

This explanation is clearly inadequate, even though it is difficult to find one which is much better.

A significant part of the Roman aristocracy, even under the emperors, was still dedicated to military prowess.

All generals were senators; all senior officers were senators or knights.

Combat in the arena gave aristocrats a chance to display their fighting skill and courage.

In spite of the opprobrium and at the risk of death, it was their last chance to play soldiers in front of a large audience.

Gladiators were glamour figures, culture heroes.

The probable life-span of each gladiator was short.

Each successive victory brought further risk of defeat and death.

But for the moment, we are more concerned with image than with reality.

Modern pop-stars and athletes have only a short exposure to full-glare publicity.

Most of them fade rapidly from being household names into obscurity, fossilised in the memory of each generation of adolescent enthusiasts.

The transience of the fame of each does not diminish their collective importance.

So too with Roman gladiators.

Their portraits were often painted.

Whole walls in public porticos were sometimes covered with life-size portraits of all the gladiators in a particular show.

The actual events were magnified beforehand by expectation and afterwards by memory.

Street advertisements stimulated excitement and anticipation.

Hundreds of Roman artefacts – sculptures, figurines, lamps, glasses – picture gladiatorial fights and wild-beast shows.

In conversation and in daily life, chariot-races and gladiatorial fights were all the rage.

When you enter the lecture halls', wrote Tacitus, 'what else do you hear the young men talking about?

Even a baby's nursing bottle, made of clay and found at Pompeii, was stamped with the figure of a gladiator.

It symbolised the hope that the baby would imbibe a gladiator's strength and courage.

The victorious gladiator, or at least his image, was sexually attractive.

Graffiti from the plastered walls of Pompeii carry the message:

Celadus [a stage name, meaning Crowd's Roar], thrice victor and thrice crowned, the young girls' heart-throb, and Crescens the Netter of young girls by night.

The ephemera of AD 79 have been preserved by volcanic ash.

Even the defeated gladiator had something sexually portentous about him.

It was customary, so it is reported, for a new Roman bride to have her hair parted with a spear, at best one which had been dipped in the body of a defeated and killed gladiator.

The Latin word for sword – "gladius" – was vulgarly used to mean penis.

Several artefacts also suggest this association.

A small bronze figurine from Pompeii depicts a cruel-looking gladiator fighting off with his sword a dog-like wild-beast which grows out of his erect and elongated penis.

Five bells hang down from various parts of his body and a hook is attached to the gladiator's head"so that the whole ensemble could hang as a bell in a doorway.

Interpretation must be speculative.

But this evidence suggests that there was a close link, in some Roman minds, between gladiatorial fighting, sexuality, and masculinity.

And it seems as though gladiatoral bravery for some Roman men represented an attractive yet dangerous, almost threatening, macho masculinity.

Gladiators attracted women, even though most of them were slaves.

Even if they were free or noble by origin, they were in some sense contaminated by their close contact with death.

Like suicides, gladiators were in some places excluded from normal burial grounds.

Perhaps their dangerous ambiguity was part of their sexual attraction.

They were, according to the Christian Tertullian, both loved and despised.

Mmen give them their souls, women their bodies too.

Gladiators were both glorified and degraded.

In a vicious satire, the poet Juvenal ridiculed a senator's wife, Eppia, who had eloped to Egypt with her favourite swordsman.

What was the youthful charm that so fired Eppia?

What hooked her?

What did she see in him to make her put up with being called 'The Gladiator's Moll'?

Her poppet, her Sergio, was no chicken, with a dud arm that prompted hope of early retirement.

Besides, his fare looked a proper mess, helmet scarred, a great wart on his nose, an unpleasant discharge always trickling from one eye.

But he was a Gladiator.

That word makes the whole breed seem handsome, and made her prefer him to her children and country, her sister and husband.

Steel is what they fall in love with.

Satire certainly, and exaggerated, but pointless unless it was also based to some extent in reality.

Modern excavators, working in the armoury of the gladiatorial barracks in Pompeii found eighteen skeletons in two rooms, presumably of gladiators caught there in an ash storm.

They included only one woman, who was wearing rich gold jewellery, and a necklace set with emeralds.

Occasionally, women's attachment to gladiatorial combat went further.

They fought in the arena themselves.

In the storeroom of the British Museum, for example, there is a small stone relief, depicting two female gladiators, one with breast bare, called Amazon and Achillia.

Some of these female gladiators were free women of high status.

Behind the brave facade and the hope of glory, there lurked the fear of death.

Those about to die salute you, Emperor.

Only one account survives of what it was like from the gladiator's point of view.

It is from a rhetorical exercise.

The story is told by a rich young man who had been captured by pirates and was then sold on as a slave to a gladiatorial trainer.

And so the day arrived.

Already the populace had gathered for the spectacle of our punishment, and the bodies of those about to die had their own death-parade across the arena.

The presenter of the shows, who hoped to gain favour with our blood, took his seat.

Although no one knew my birth, my fortune, my family, one fact made some people pity me.

I seemed unfairly matched.

I was destined to be a certain victim in the sand.

All around I could hear the instruments of death: a sword being sharpened, iron plates being heated in a fire [to stop fighters retreating and to prove that they were not faking death], birch-rods and whips were prepared.

One would have imagined that these were the pirates.

The trumpets sounded their foreboding notes; stretchers for the dead were brought on, a funeral parade before death. Everywhere I could see wounds, groans, blood, danger.

He went on to describe his thoughts, his memories in the moments when he faced death, before he was dramatically and conveniently rescued by a friend.

That was fiction.

In real life gladiators died.

Why did Romans popularise fights to the death between armed gladiators?

Why did they encourage the public slaughter of unarmed criminals?

What was it which transformed men who were timid and peaceable enough in private, as Tertullian put it, and made them shout gleefully for the merciless destruction of their fellow men?

Part of the answer may lie in the simple development of a tradition, which fed on itself and its own success.

Men liked blood and cried out for more.

Part of the answer may also lie in the social psychology of the crowd, which relieved individuals of responsibility for their actions, and in the psychological mechanisms by which some spectators identified more easily with the victory of the aggressor than with the sufferings of the vanquished.

Slavery and the steep stratification of society must also have contributed.

Slaves were at the mercy of their owners.

Those who were destroyed for public edification and entertainment were considered worthless, as non-persons; or, like Christian martyrs, they were considered social outcasts, and tortured as one Christian martyr put it as if we no longer existed.

The brutalisation of the spectators fed on the dehumanisation of the victims.

Rome was a cruel society.

Brutality was built into its culture in private life, as well as in public shows.

The tone was set by military discipline and by slavery.

The state had no legal monopoly of capital punishment until the second century AD.

Before then, a master could crucify his slaves publicly if he wished.

Seneca recorded from his own observations the various ways in which crucifixions were carried out, in order to increase pain.

At private dinner-parties, rich Romans regularly presented two or three pairs of gladiators.

When they have finished dining and are filled with drink, wrote a critic in the time of Augustus, 'they call in the gladiators.

As soon as one has his throat cut, the diners applaud with delight.

It is worth stressing that we are dealing here not with individual sadistic psycho-pathology, but with a deep cultural difference.

Roman commitment to cruelty presents us with a cultural gap which it is difficult to cross.

Popular gladiatorial shows were a by-product of war, discipline and death.

For centuries, Rome had been devoted to war and to the mass participation of citizens in battle.

They won their huge empire by discipline and control.

Public executions were a gruesome reminder to non-combatants, citizens, subjects and slaves, that vengeance would be exacted if they rebelled or betrayed their country.

The arena provided a living enactment of the hell portrayed by Christian preachers.

Public punishment ritually re-established the moral and political order.

The power of the state was dramatically reconfirmed.

When long-term peace came to the heartlands of the empire, after 31 BC, militaristic traditions were preserved at Rome in the domesticated battlefield of the amphitheatre.

War had been converted into a game, a drama repeatedly replayed, of cruelty, violence, blood and death.

But order still needed to be preserved.

The fear of death still had to be assuaged by ritual.

In a city as large as Rome, with a population of close on a million by the end of the last century BC, without an adequate police force, disorder always threatened.

Gladiatorial shows and public executions reaffirmed the moral order, by the sacrifice of human victims – slaves, gladiators, condemned criminals or impious Christians.

Enthusiastic participation, by spectators rich and poor, raised and then released collective tensions, in a society which traditionally idealised impassivity.

Gladiatorial shows provided a psychic and political safety valve for the metropolitan population.

Politically, emperors risked occasional conflict, but the populace could usually be diverted or fobbed off.

The crowd lacked the coherence of a rebellious political ideology.

By and large, it found its satisfaction in cheering its support of established order.

At the psychological level, gladiatorial shows provided a stage for shared violence and tragedy.

Each show reassured spectators that they had yet again survived disaster.

Whatever happened in the arena, the spectators were on the winning side.

They found comfort for death' wrote Tertullian with typical insight, in murder.

Further reading:

- An expanded version of this article with references appears in K. Hopkins, Death and renewal, Sociological Studies in Roman History , Volume 2 (Cambridge University Press, May 1983)

- The most extensive review of the evidence on gladiatorial games is by L. Friedlaender, Roman Life and Manners , Volume 2 with references in Volume 4 (London, 1913)

- A more accessible and readable account is given by M. Grant, Gladiators , (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1976)

No comments:

Post a Comment