LA TEBAIDE is a Latin epic in twelve books written in dactylic hexameter by Publio Papinio Stazio (AD c. 45 – c. 96).

The poem deals with the Theban cycle and treats the assault of the seven champions of Argos against the city of Thebes.

Based on Stazio's own testimony, the Thebaid was written c. 80 – c. 92 AD, and the work is thought to have been published in 91 or 92.[1]

According to the last verse of the poem, Stazio wrote the Tebaide over the course of a dozen years during the reign of Emperor Domiziano, although the symmetry of the compositional period, assigning one book per year, has been taken with suspicion by scholars.[3]

The poem is divided into 12 books in imitation of Virgil's ENEIDE and is composed in 9,748 hexameter verses, the standard meter of Greco-Roman epics.

In the Silvae, Stazio speaks of his extensive work in polishing and revising the Tebaide and his public recitations of the poem.

From the epilogue it seems clear that Stazio considered the Tebaide to be his magnum opus and believed that it would secure him fame for the future.

Statius' Thebaid deals with the same subject as the Thebaid – an early Greek epic of several thousand lines which survives only in brief fragments (also known as the Thebais), and which was attributed by some classical Greek authors to Homer.

Perhaps a more important source for Stazio was the long epic Thebais of Antimachus of Colophon, an important poem both in the development of the Theban cycle and the evolution of Hellenistic poetry.[8]

Also significant for Statius were the myth's many treatments in Greek drama, represented by surviving plays such as Aeschylus' The Seven Against Thebes, Sophocles' Antigone, and Euripides' Phoenissae and Suppliants.

Other authors provided models for specific sections of the poem; the Coroebus episode in Book 1 may be based on Callimachus' Aetia, while the Hypsipyle narrative in Book 5 echoes Apollonius of Rhodes' treatment.

**********************************************

On the Latin side, Statius is highly indebted to Virgilio, a debt he acknowledges in his epilogue.[9]

Stazio emulates Homer's Odyssean and Iliadic book division, concentrating aetiological material and traveling in the first six books and focusing on battle narratives in the second six, and many episodes allude to sections in the Eneide -- such as the correspondence of the Dima and Opleo episode to Nisus and Euryalus.

Ovidio's considerable influence can be traced in Stazio's handling of cosmic structure, description, style, and verse.

Ovid in some ways seems to be more a model for Statius than Virgil at times.

The influence of Lucano can be particularly felt in Statius' penchant for macabre battle sequences, discussion of tyranny, and focus on nefas.[12]

Seneca's tragedies also seem to be an influence in the Thebaid, particularly in Statius' portrayal of family relations, generational curses, necromancy, and insanity.

LIBRO 1.

The Thebaid opens with a priamel in which the poet rejects several themes dealing with Theban mythology and decides to focus on the House of Oedipus (Oedipodae confusa domus), and following this is a recusatio and a passage in praise of Domiziano.

The narrative begins with Oedipus' prayer to the chthonic gods and curse on his sons Polyneices and Eteocles who have rejected and mistreated him.

The Fury Tisiphone hears Oedipus' prayer and ascends to the earth to fulfill the curse, causing strife between Eteocles and Polyneices.

POLYNEICES is in exile for a year while Eteocles holds the throne of Thebes.

This is followed by a council of the gods concilium deorum at which GIOVE informs the gods of his plan to involve Thebes and Argos in a war.

When GIUNONE passionately pleas for Argos, she is silenced by Giove's unshakable decision.

Mercurio is sent to the underworld to fetch the shade of Laio to cause drive Eteocle to war.

Meanwhile Polyneices is driven by a storm to Argos and the threshold of Adrastus's palace, where he meets Tydeus, an exile from Calydon who is also seeking shelter, and fights with him.

Adrastus invites the two exiles in, feasts them, and, in fulfillment of a prophecy, offers them his daughters to marry.

He then goes on the explain the aetiology of the festival the Argives are celebrating, telling the story of Apollo's rape of Psamathe, the death of her and her child Lino, followed by Apollo's vengeful summoning of a child-eating monster from the underworld which later was slain by Coroebus, and finally, Coroebus' offer of self-sacrifice to Apollo to end a plague at Argos.

The book ends with Adrastus' prayer to Apollo.

***************************

LIBRO or CANTO 2.

The second book begins with Mercury's guidance of the shade of Laius to Thebes.

Laius appears in the guise of Tiresias to Eteocles in a dream and drives him to refuse to allow Polyneices to become king when his year is over.

The poet describes the necklace of Harmonia, which Argia wears to the wedding, as an object that brings its bearers bad luck and causes strife.

Polyneices sends Tydeus on an embassy to Eteocles to remind him that his time of rule is over. Eteocles refuses Tydeus' request for him to give up the throne. Tydeus leaves in a rage and Eteocles sends an ambush to kill him as he returns in a mountain pass. Tydeus kills all the ambushers except Maeon so he can carry the news back to Eteocles. Tydeus then attaches the battle trophies—taken from the slain—to an oak tree as he prays to Minerva.

Book 3 Maeon returns to Thebes, reports the slaughter to Eteocles, criticizing the tyrant's behavior, and then commits suicide. The Thebans go out to survey the slaughter and bury the dead. Jupiter orders Mars to go to earth to stir up war, but Venus blocks his chariot, beseeching him to prevent the war. Mars follows Jupiter's commands and heads to earth, stirring up trouble in the cities and driving Adrastus and Polyneices to declare war once they hear of Eteocles' outrage. Amphiaraus and Melampus go to Aphesas to take auspices about the coming war, which portend confusion, violence, and death. The Argives and their allies prepare their forces. Argia, sympathetic to Polyneices' restlessness, appeals to Adrastus to hasten the war.

Book 4 Book 4 opens three years after the third book. The Argives and their allies are gathered and the poet asks Fama and Vetustas to help him in the catalogue of heroes and allies. Each hero's armor and appearance are described. Adrastus and Polyneices muster the Argive forces, Tydeus the Aetolians, Hippomedon the Dorians, and Capaneus the Messenians. Amphiaraus is driven to fight by Eriphyle and leads the Spartans, while Parthenopaeus unbeknownst to his mother, Atalanta, leads the Arcadians. The Thebans reluctantly prepare for war. Because of bad omens, Tiresias, Eteocles, and Manto go to the grove of Diana to perform necromancy. Manto and Tiresias have a vision of the underworld and find the spirit of Laius which tells them that Thebes will be victorious but terrible crimes will occur. As the Argives march through Nemea, Bacchus causes a drought for the army. The army encounters Hypsipyle who is nursing the child Opheltes (Archemorus). She leaves the boy and shows the Argives a spring where they finally find water; the book ends with praise for Nemea.

Book 5 Asked by the Argives who she is, Hypsipyle tells her story. To punish the island of Lemnos for ignoring her worship, Venus drives the women of the island to kill all the men. Hypsipyle saves her father, Thoas, setting him adrift at sea in a chest. Just as the Lemnian women despair of their future, the Argonauts arrive, sleep with the women, and soon leave. When Hypsipyle's rescue of her father is revealed, she flees Lemnos and becomes a nurse to Opheltes. As Hypsipyle talks, a snake crushes Opheltes, which is killed by the Argives. King Lycurgus and Eurydice mourn their son, and the Argives suggest the institution of the Nemean games to commemorate Opheltes.

Book 6 The Argives burn Opheltes on a massive pyre, and funeral sacrifices are performed while Eurydice recites a lament. Nine days later, contestants gather for the new Nemean Games which include chariot racing, which Amphiaraus wins, foot races, at which Parthenopaeus is cheated of an easy victory, and a discus contest, which Hippomedon wins. Capaneus is almost killed in the boxing, and Tydeus wins in the wrestling. The book ends with Adrastus' ill-omened attempt at archery.

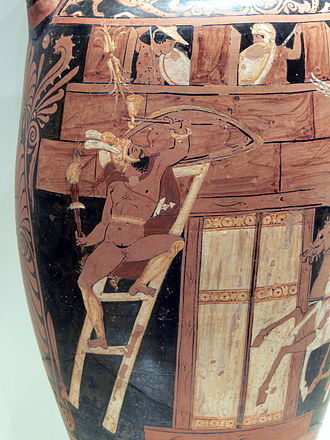

Book 7 Jupiter, angry at the Nemean delay, sends Mercury to the Thracian temple of Mars to stir the army. Mars sends Panic into the Argive army to frighten the soldiers who resume their march. Bacchus pleads to Jupiter to avert the war in vain as the Argives arrive at Thebes with terrible omens. Antigone and an old servant look at the army from a tower and describe the heroes (teichoscopia) and Jocasta tries to dissuade Eteocles from fighting. The Argives kill two tigers sacred to Bacchus and stir the Thebans to battle. The poet invokes the muse as he begins to describe the first skirmish where Apollo gives Amphiaraus an aristeia. During battle, the earth opens and swallows Amphiaraus and his chariot.

*********************

LIBRO 8.

As Amphiaraus descends, Plutone, threatened by this violation of his realm, sends Tisiphone to create crimes in the war.

The Thebans celebrate after the battle while Melampo propitiates Tello with sacrifices in the Argive camp.

Stazio invokes Calliope when the battle is joined again.

Both sides make gains in the fighting, but Atys, Ismene's betrothed, is killed and his corpse brought to Edipus.

Tideo is wounded by Melanippo.

Tideo then slays Melanippo and eats Melanippo's head.

Book 9.

TIDEO dies and the armies struggle for the body.

Tisifone drives Iippomedon to enter the fray and recover the body and the hero has an aristeia.

There is a battle in the river Ismeno and Iippomedon is killed when the river floods to avenge its grandson at the behest the boy's mother, Ismeni.

The heroes fight for the body of Ippomedon and Ipseus dies.

Atalanta in Arcadia has a dream of Parthenopaeo's death and prays to Diana who gives him an aristeia before he is killed by Dryas.

*********************************

LIBRO 10

The Thebans celebrate as the wives of the heroes in Argos perform sacrifices to Giunone.

GIUNONE sends Iris to the grove of Sleep who puts the Theban army into a deep sleep during the night.

A band of soldiers is gathered by the Argives which enters the Theban camp and slaughters the sleeping warriors.

The pair Dymas and Hopleus kill many Thebans and are slain together.

The Thebans awake and flee into the city.

There is battle at the gates, which are eventually closed.

Tiresia demands the death of Menoeceo for the war to end.

Menoeceo leaps from the walls.

Capaneo climbs a tower and curses Giove who kills him with a thunderbolt.

**********

LIBRO 11

The Argives are driven by the Thebans to their camp.

Tisiphone and Megera stir Polyneice to challenge Eteocle to single combat to decide the war.

Giocasta and Antigona try to dissuade them, but they go out into the plain to fight.

Fortuna and Pietas try to delay the fight but are driven away by the furies.

The brothers kill each other.

Edipo laments as Giocasta kills herself at the news.

Creon assumes power, forbids the burial of Polyneice and the Argive dead, and exiles Edipo while the Argives quietly return home.

LIBRO 12

The Thebans bury their dead.

The Argive widows travel to Tebes to bury their dead relatives but receive the news that Creon has denied them burial.

The women travel to Athens to ask Teseus to help them.

Argia secretly comes to Thebes and meets Antigone outside the wall.

They burn the bodies of the brothers on one pyre, but the flames separate.

Creon arrests the women as the widows become suppliants at the altar of Clementia at Athens.

Teseo prepares an army against Tebes and slays Creon in battle.

The Tebaide ends with an epilogue in which the poet prays that his poem will be successful, cautions it not to rival the Aeneid, and hopes that his fame will outlive him.

***************************

The Tebaide was popular in Stazio's lifetime and (according to the epic’s final verse), Roman schoolboys were already memorizing passages from the epic before it was finished.

Stazio was personally favored by Emperor Domiziano, and the educational use of his poem might be seen as a consequence of official favor.

However, the TEBAIDE remained a popular piece of Latin literature for many centuries, a testimony to its literary merit and lasting appeal.

A commentary on the Tebaide is transmitted under the name of Lactanzio Placido, dating from the 5th or 6th century AD, which has proven useful to modern scholars.

In the late 12th century a French verse romance, IL ROMANZO DI TEBE, was composed by an unknown author, probably at the court of Henry II of England.

Here the Tebaide is transformed into a chivalric epic.

Giovanni Boccaccio, the 14th-century Italian poet and author best known for writing the Decameron, also borrowed heavily from the Tebaide when composing his Teseida which, in turn, was used heavily by Chaucer when composing The Knight’s Tale for the Canterbury Tales.

Of particular importance is a scene in which Mercurio is sent to the realm of Marte.

All three of these works (as well as Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene) contain large tracts of allegorical figures that are housed in War’s realm and which represent the various futilities of war and violence.

Finally, one of the chief reasons that Stazio is remembered today is because of the poet Dante Alighieri.

Like Virgil, who is a character in the first two books of Dante’s Divine Comedy, Stazio, too, plays a large role in the Comedy.

Dante and Virgil meet Statius in Purgatory, and he accompanies the two to the Earthly Paradise at the summit of the holy mountain.

Through the medium of Dante, Stazio gets to meet his precursor, Virgil, and praise him personally.

This scene is justified as the historical Statius devoted the closing lines of his Thebaid to praise of Virgil.

Despite its popularity in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the Tebaide's reputation suffered in 19th and early 20th century scholarship.

Scholars of that era considered Statius "derivative" and unoriginal and criticized his seemingly positive view of Domitian's regime.

In the late 20th century, scholars have attempted to rehabilitate Statius.

A series of new translations have been accompanied by a slew of studies which seek to bring Stazio back into the classical canon.

Criticism of Statius' has been forced to deal with the Stazio's flattering attitude to the repressive emperor Domiziano in his Silvae and his seeming vindication of the regime in the Thebaid.

Scholars of the early 20th century dismissed Stazio as a mere panegyrist for a tyrant.

More recent scholars have taken the opposite view of Stazio and interpreted the Thebaid as a criticism of civil war and the Flavian dynasty's rise to power.

The cruelty and madness of the characters have been interpreted as symbolic of the cruel behavior of Domitian and his officials.

The prominence of suicide in the Thebaid has also been linked with the concept of suicide as social protest found in Tacito.

There is a drastic imbalance in the poem which privileges violence over peace and the focus is on disrupted succession.

Scholars have also looked at Statius' funeral games and their connection to the poetic competitions Statius participated in.

The style of the Thebaid has been described as episodic by scholars.

In the past, this was considered a major flaw but has since been reevaluated.

Scholars have noticed a strong degree of control over the arrangement of episodes, description, and teleological narrative and point out the way that the poem's juxtapositions emphasize certain structural devices in the text.

The development of inter-textual readings has similarly shown that Stazio's imitation of Virgil and other poets is often highly astute and creative.

The importance of rhetoric, another point of criticism from earlier scholars, has also been studied in the Thebaid.

It is often through SPEECHES that Stazio develops his character rather than through narrative description and Statius' has been shown to be a masterful handler of rhetorical technique.

Like the majority of epics that precede him (with the notable exception of Lucano's FARSAGLIA), Stazio makes full use of the gods as plot devices.

However, Stazio employs them in his own creative way.

The role and effectiveness of the Olympian gods is drastically reduced in comparison with cthonic deities.

GIOVE's power in particular is usurped by the gods of the underworld, personifications and allegories, and human heroes (like Theseus).[22]

In his depiction of the gods, C. S. Lewis sees Stazio's technique as a departure from Homer's and Vergil's more mythological treatment.

Statius' development of allegory was an important step towards allegory's domination in Medieval literature.

To illustrate the difference, Lewis contrasts Homer's MARTE, who does other things besides rage in war, with Stazio's MARTE, a personification of an abstraction, who even before the battle begins is always already raging in his blind and insane passion.

Lewis further claims that on account of this difference, in the Thebaid lies the germ of all the allegorical poetry."

Important quotes[edit]

Fraternas acies alternaque regna profanes decertata odiis sontesque evolvere Thebas

Pierius menti calor incidit

Fraternal warfare and alternate reigns, fought for in unnatural hate, and guilty Thebes

Pierian fire falls on me to unfold. Theb. 1.1–3, D. R. Shackleton-Bailey, trans.

vive, precor; nec tu divinam Aeneida tempta, sed longe sequere et vestigia semper adora.

mox, tibi si quis adhuc praetendit nubila livor occidet, et meriti post me referentur honores.

So thrive, I pray, but do not envy the divine Aeneid. Follow well back. Always adore her traces. If any envy clouds you, it will fade; When I am gone, due honour will be paid.

—Theb. 12.816–819, Charles Stanley Ross, trans.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- Jump up ^ Feeney, Dennis The Oxford Classical Dictionary (Oxford, 1996) pg.1439

- Jump up ^ Theb 12.811

- Jump up ^ Feeney, pg.1439

- Jump up ^ Shackleton-Bailey, D.R. Statius' Thebaid 1-7 (Cambridge, 2003) pg.3

- Jump up ^ Silv. 4.7.26

- Jump up ^ Silv. 5.2.161

- Jump up ^ Theb. 810-819

- Jump up ^ Bailey, pg.2

- Jump up ^ Theb. 810ff.

- Jump up ^ Theb. 10.448, where a striking mythological simile connects the two sets of heroes.

- Jump up ^ Feeney, pg.1439

- Jump up ^ Feeney, pg.1439

- Jump up ^ Feeney, pg.1439

- Jump up ^ Bailey pg.3

- Jump up ^ Encyclopædia Britannica 11th ed. s.v. Statius.

- Jump up ^ Kaster, Robert in The Oxford Classical Dictionary, (Oxford, 1996) pg.811

- Jump up ^ Coleman in Bailey, pg.10-13

- Jump up ^ Hardie, P. The Epic Successors of Virgil: A Study in the Dynamics of a Tradition (Cambridge, 1993).

- Jump up ^ Thuillier, J. Stace, Thebaide 6: les jeux funebres et les realities sportives (Nikephoros 9, 1996)

- Jump up ^ Coleman in Bailey, pg.13-18

- Jump up ^ Coleman in Bailey, pg.17-18

- Jump up ^ Feeney, D. The Gods in Epic (Oxford, 1991)

- Jump up ^ Lewis, C. S. The Allegory of Love (1936) pp.48-56)

- Jump up ^ Lewis, pg.54

Bibliography:

The Mythic Voice of Stazio: Power and Politics in the Tebaide (Leiden, 1994).

- Text from the Latin Library

- Mozley's translation

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Categories:

- 1st-century books

- Epic poems in Latin

- Poetry by Stazio

- Graeco-Roman mythology

No comments:

Post a Comment