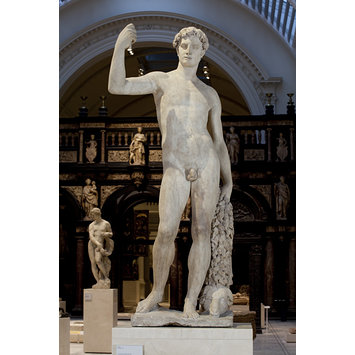

Jason

- Object:

Statue

- Place of origin:

Italy (made)

- Date:

2nd half 16th century (carved)

- Artist/Maker:

unknown (production)

- Materials and Techniques:

Marble

- Museum number:

6735-1860

- Gallery location:

Medieval and Renaissance, room 50a, case FS

In the Renaissance gardens were often associated with the earthly paradises of classical mythology.

The story of Giasone includes the sacred grove of the Golden Fleece and the Garden of the Hesperides, making him a suitable subject for a garden.

This sculpture once stood in a portico in the garden of the Palazzo Stiozzi-Ridolfi in Firenze. (The present owners of the villa want it back, incidentally).

Although one of the most famous of the Greek heroes, Giasone is not widely represented in Renaissance art.

The revival of interest in classical art and literature in Renaissance Italy should have made him a fitting subject, however he does not occur with the fequency of other greek heroes such as Ercole.

The story of Giasone was first written in the 200s BC by the Alexandrian poet Apollonius of Rhodes. According to the Argonautica written by Apollonius, Jason led the Argonauts on their voyage to capture the Golden Fleece from Aeetes, King of Colchis on the Black Sea.

The King's daughter Medea fell in love with Jason, and by her skill in magic helped him overcome various mortal dangers and win the fleece, which hung from the branch of a tree guarded by a dragon. Having won the fleece Jason and Medea fled from the wrath of Aeetes back to Greece. Jason later abandoned Medea and married a Greek woman causing Medea to seek revenge.

Giasone is shown nude in full-length. In his left hand he holds the golden fleece, in his right the shaft of a spear. The figure rests on a shallow rectangular base.

The figure has suffered extensive damage and in the case of some parts of the sculpture it is not possible to establish whether they are original or not. Two locks of hair over the forehead, the front of the nose and the penis have been identified as being of unquestionably nineteenth century origin. The principal breaks in the sculpture, are in the area of the upper arm, neck and left shoulder, with the addition of plaster make-up. One piece of marble in the neck has been wrongly replaced. the head is presumed to be original , although the features may have been reworked and its placing on the body may not be necessarily correct. Pope-Hennesy expresses doubts concerning the authenticity of the right lower arm, in which the wrist is crudely carved; the form of the nail of the thumb of the right hand differs from that on the left. The right arm was however already in position in 1832.on a classical example.

Place of Origin

Italy (made)

Date

2nd half 16th century (carved)

Artist/maker

unknown (production)

Materials and Techniques

Marble

Height: 182.9 cm, Width: 80 cm, Depth: 58 cm

Stated (MS. note at the time of acquisition) to have been obtained

"from the gardens of the Palazzo Strozzi (sic), Florence, where it formerly stood under the portico 'Degli Orti Oricellari'".

The Pallazo Stiozzi-Ridolfi, formerly Palazzo Rucellai, to which this statement refers is that in the Orti Oricellari.

A lithograph published in 1832 (Vedute del Giardino del Mar: Stiozzi-Ridolfi gia Orti Oricellari, Florence 1832) shows the statue on a high pedestal niche or arbour at the end of the Viale di Baco in the Orti Oricellari. The lithograph shows that the spear held in Jason's right hand was already broken in 1832.

The gardens were thoroughly remodelled twice after they were laid out. The first alterations were made between 1640 and 1663, when the gardens were the possession of Cardinal Gian Carlo de' Medici. The second period of alteration took place in about 1819, when the gardens were laid out in the English style by Marchese Giuseppe Stiozzi. The sale of Jason preceded the general disposal of the statuary from the Orti Oricellari between 1863 and 1891. It cannot be established whether or not the statue formed part of the sixteenth century garden decorations.

Ascribed by J.C Robinson to "one of the earliest scholars of Michael Angelo" active about 1530 the statue has been tentatively associated with Jacopo Sansovino by Burckhardt. It has been suggested by Maclagan and Longhurst that the figure is identical with a statue of Jason carved by Giovanni Bandini for Minsignor Ugolino Grifoni. Attribution to Bandini rejected by Middledorf on the grounds that the plastic conception is richer than is usual in Bandini's sculpture. Pope-Hennessy concludes that the stylistic affiliations of the sculpture are closer to those of Ammanati than Bandini., with both the pose and the handling reminiscent of the Florence in the Boboli Gardens and the Maturity of counsel in the Bargello. Pope-Hennessy records that a tentative ascription to Ammanati's pupil Andrea Calamecca (1524-1589) has been proposed (verbally) by Holderbaum.

A statue of Jason with the Golden Fleece by Francavilla, noted by Maclagan and Longhurst and now in the Pallazo Ricasoli.

Although one of the most famous of the Greek heroes, Jason is not widely represented in Renaissance art. The revival of interest in classical art and literature in Renaissance Italy should have made him a fitting subject, however he does not occur with the fequency of other greek heroes such as Hercules. One other surviving example was carved by Francavilla recorded by Pope Hennesy as residing in the Palazzo Ricasoli.

The story of Jason was first written in the 200s BC by the Alexandrian poet Apollonius of Rhodes. According to the Argonautica written by Apollonius, Jason led the Argonauts on their voyage to capture the Golden Fleece from Aeetes, King of Colchis on the Black Sea. The King's daughter Medea fell in love with Jason, and by her skill in magic helped him overcome various mortal dangers and win the fleece, which hung from the branch of a tree guarded by a dragon. Having won the fleece Jason and Medea fled from the wrath of Aeetes back to Greece. Jason later abandoned Medea and married a Greek woman causing Medea to seek revenge.

Renaissance gardens were often referred to as a paradise (for a fourteenth-century example see Boccaccio's Decamron: "se paradiso si potesse in terra fare, non sapevano conoscere che altra forma quella di quel giardino gli si potesse dare..." in the fifteenth-century, Arienti's Art and Life: "Questo felicissimo zardino ne fa pensare la delicia de quello del regno del Paradiso" and in the sixteenth-century Ulisse Aldrovandi described the Vigna Carpi as "à punto un Paradiso terrestre"). Gardens were identified with the earthly paradises of classical mythology – the Golden Age, The Garden of Hesperides and Arcadia. A figure of Jason would have been particularly appropriate for a garden context; his myth associates him with the sacred grove of the Golden Fleece and the Garden of The Hesperides.

The Orti Oricellari were the grand Florentine gardens created by Bernardo Rucellai (1449-1514).The gardens adjoined the Pallazzo Rucellai designed for Bernardo's father Giovanni, by Alberti. Bernardo married Nannia de Medici (the sister of Lorenzo the Magnificent) in 1460 and following the death of Lorenzo in 1492 he offered the gardens as a meeting place for the Plato Academy, which had previously met at the Medici Villa Careggi. The gardens became famous as a gathering place for humanists, philosophers and poets and also for the sculptures collected by Bernardo. A keen collector of artistic antiquities he gathered illuminated manuscripts and pictures in the Pallazo and sculptures and inscribed antiquities in the gardens. The sculpture collection was comprised of busts of emperors, orators and poets which had been dug up in the excavations of Rome, under Raphael and San Gallo, had been brought from Greece or stolen following the exile of the Medici in 1494. The gardens were also the place where the conspiracy of 1522 against Cardinal Giuliano de Medici was hatched. The Rucellai family were un-connected to the plot however it brought an end to the activities of the Plato academy in the garden. The garden was sacked in by a Florentine mob in 1527 when Palla Rucellai, the son of Bernardo, was driven out of the city for his connection to oppressive Cardinal Passerini. The mob broke into the garden, mutilated the trees and broke the statuary, the Palazzo was also plundered. Palla was to regain the gardens on his return to the city as envoy of Pope Clement VII and he re-established the gardens sufficiently to entertain the Emperor Charles V who enjoyed a feast in the branches of a gigantic elm tree in which Palla had room.

The villa was sold by one of Palla's sons to Bianca Capello in 1573 under whom the gardens lost their classic severity and became a stage for burlesque entertainments. Bianca lived a colourful life. Exiled from Venice she became the secret wife of the Grand Duke following the murder of her husband and attempted to pass off an impostor as her son having had him smuggled through the gardens in a kind of lute. She died in 1587 when the gardens passed to the Orsini family.

Statue of Jason in marble, Florentine, second half 16th century

BIBLIOGRAFIA

Lazzaro, P. The Italian Renaissance Garden (Yale University Press, 1990) p132

For the Garden as paradise

Pope-Hennessy, J. Catalogue of Italian Sculpture in the Victoria and Albert Museum (London, H.M.S.O. 1964) pp.485, 486 cat. no. 514

Robinson, J.C Italian sculpture of the Middle Ages and period of the revival of art (London, H.M.S.O. 1862) p148-149

Ascribed to one of the earliest scholars of Michael Angelo

Burckhardt Beitrage zur unstgeschichte von Italien (Berlin and Stuttgart, 1911) p. 423

Associates the statue with Jacopo Sansovino

Maclagan and Longhurst Catalogue of Italian Sculpture in the Victoria and Albert Museum (London, 1932) p.144

Suggest that the figure is identical with a statue of Jason carved by Giovanni Bandini for Monsignor Ugolino Grifoni - rejected by Middeldorf

Inventory of Art Objects Acquired in the Year 1860. In: Inventory of the Objects in the Art Division of the Museum at South Kensington, Arranged According to the Dates of their Acquisition. Vol I. London: Printed by George E. Eyre and William Spottiswoode for H.M.S.O., 1868, p. 41

Avery, Charles. "Giovanni Bandini (1540-1599) Reconsiderd". In: Antologia di Belle Arti, La Scultura, Studi in onore di Andrew S Ciechanowiecki. nn. 48-51, 1994, pp. 24-25

Utz, Hildegard. "Domencio Poggini". Metropolitan Museum of Art Journal, 1975, pp. 63-76. (attributes the Jason to Poggini)

Pope-Hennessy suggests that the present figure, is stylistically affiliated rather to Ammanati than Bandini, and both the pose and the handling are reminsicent of the Florence Boboli Gardens and the Maturity of Counsle in the Bargello. A tentative ascription to Ammanati's pupil Andrea Calamecca is proposed by Holderbaum. (cit. Pope-Hennessy, pp. 485, 486)

Materials

Marble

Subjects depicted

Golden Fleece; Jason

Categories

Sculpture

Collection code

SCP

No comments:

Post a Comment