* * * * * A * * * * *

ADORNO, Gabriele. Fifth doge of Genoa.

Boccanegra erano di nobiltà recente; il primo di loro ad emergere fu Guglielmo Boccanegra, nominato Capitano del Popolo, che fece erigere nel 1260 il Palazzo San Giorgio, sede della massima autorità Comunale. Da fuoruscito in Francia, ad Aigues-Mortes progettò le mura di quella città per il re di Francia. Simone Boccanegra ebbe a Genova un ruolo analogo se non ancora più ampio di questo suo primo antenato. Boccanegra fu il primo Doge della Repubblica, acclamato a vita il 23 dicembre 1339. Il titolo della Repubblica di Genova a quel tempo era, in realtà, più propriamente chiamato - secondo il dialetto genovese, "duxe" (cuce). Con la nomina di Boccanegra ebbe inizio l'età dei Dogi perpetui e della cosiddetta egemonia popolare che avrebbe contraddistinto il governo nella Repubblica di Genova. Nel 1363 Simone Boccanegra morì, avvelenato per mano di sicari delle famiglie Adorno e Fregoso che da quel momento acuirono la loro lotta per contendersi il controllo del dogato. In Giuseppe Verdi, "Simon Boccanegra". Time: The middle of the 14th century. Place: In and around Genova. The Prologue is set in a piazza in front of the Fieschi palace. Paolo Albiani, a plebeian, tells his ally Pietro that in the forthcoming election of the Doge, his choice for the plebeian candidate is Simon Boccanegra. Boccanegra arrives and is persuaded to stand when Paolo hints that, if Boccanegra becomes Doge, the aristocratic Jacopo Fiesco will surely allow him to wed his daughter Maria. When Boccanegra has gone, Paolo gossips about Boccanegra's love affair with Maria Fiesco. Boccanegra and Maria have had a child, and the furious Fiesco has locked his daughter away in his palace. Pietro rallies a crowd of citizens to support Boccanegra. After the crowd has dispersed, Fiesco comes out of his palace, stricken with grief. Maria has just died (Il lacerato spirito – "The tortured soul of a sad father"). Fiesco swears vengeance on Boccanegra for destroying his family. When Fiesco meets Boccanegra, Fiersco does not inform him of Maria's death. Boccanegra offers reconciliation and Fiesco promises clemency only if Boccanegra lets him have his granddaughter. Boccanegra explains he cannot because the child, put in the care of a nurse, has vanished. He enters the palace and finds the body of his beloved just before crowds pour in, hailing him as the new Doge. Act 1. The first Scene is set in A garden in the Grimaldi palace, before sunrise. Twenty-five years have passed and Boccanegra has exiled many of his political opponents and confiscated their property. Among Boccanegra's political enemies is Fiesco, who has been living in the Grimaldi palace, using the name "Andrea Grimaldi" to avoid discovery and plotting with Boccanegra's enemies to overthrow the Doge. The Grimaldis have adopted an orphaned child of unknown parentage after discovering her in a convent. She is in fact Boccanegra's child and Fiesco's granddaughter They called her "Amelia", hoping that she would be the heir to their family's fortune, their sons having been exiled and their own baby daughter having died. Amelia is now a young woman. Amelia is awaiting her lover, Gabriele Adorno (Aria:Come in quest'ora bruna – "How in the morning light / The sea and stars shine brightly"). Amelia suspects Gabriele Adorno of plotting against Boccangra. When Boccanegra arrives, Amelia warns him of the dangers of political conspiracy. Word arrives that the Doge is coming. Amelia, fearing that the Doge will force her to marry Paolo, now his councillor, urges Adorno to ask her guardian Andrea Grimaldi (in reality, Fiesco) for permission to marry. Fiesco reveals to Gabriele Adorno that Amelia is not a Grimaldi, but a foundling adopted by the family. Gabriele Adorno says that he does not care. Fiesco blesses the marriage. Boccanegra enters and tells Amelia that he has pardoned her exiled brothers. Amelia tells him that she is in love, but not with Paolo who she refuses to marry. Boccanegra has no desire to force Amelia into a marriage against her will. Amelia tells him that she was adopted and that she has one souvenir of her mother, a picture in a locket. The two compare Amelia's picture with Boccanegra's, and Boccanegra realizes that she is his long-lost daughter. Finally reunited, they are overcome with joy. Amelia goes into the palace. Soon after, Paolo arrives to find out if Amelia has accepted him. Boccanegra tells him that the marriage will not take place. Furious, Paolo arranges for Amelia to be kidnapped. The second is set in The council chamber Boccanegra encourages his councillors to make peace with Venice. Boccanegra is interrupted by the sounds of a mob calling for blood. Paolo Albiani suspects that his kidnapping plot has failed. Boccanegra prevents anyone leaving the council chamber and orders the doors to be thrown open. A crowd bursts in, chasing Gabriele Adorno. Gabriele Adorno confesses to killing Lorenzino, a plebeian, who had kidnapped Amelia, claiming to have done so at the order of a high-ranking official. Gabriele Adorno incorrectly guesses the official was Boccanegra and is about to attack him when Amelia rushes in and stops him (Aria: Nell'ora soave – "At that sweet hour which invites ecstasy / I was walking alone by the sea"). Amelia describes her abduction and escape. Before Amelia is able to identify her kidnapper, fighting breaks out once more. Boccanegra establishes order and has Gabriele Adorno arrested for the night (Aria: Plebe! Patrizi! Popolo! – "Plebians! Patricians! Inheritors / Of a fierce history"). Boccanegra orders the crowd to make peace and they praise his mercy. Realizing that Paolo Albiani is responsible for the kidnapping, Boccanegra places him in charge of finding the culprit. He then makes everyone, including Paolo Albiani, utter a curse on the kidnapper. The Act 2 opens in The Doge's apartments. Paolo Albiani has imprisoned Fiesco. Determined to kill Boccanegra, Paolo Albiani pours a slow-acting poison into Boccanegra's water, and then tries to convince Fiesco to murder Boccanegra in return for his freedom. Fiesco refuses. Paolo Albiani next suggests to Gabriele Adorno that Amelia is the Doge's mistress, hoping Adorno will murder Boccanegra in a jealous rage. Gabriele Adorno is furious (Aria: Sento avvampar nell'anima – "I feel a furious jealousy / Setting my soul on fire"). Amelia enters Boccanegra's apartments, seeming to confirm Gabriele Adorno's suspicions. Gabriele Adorno angrily accuses her of infidelity. Amelia claims only to love Gabriele Adorno, but cannot reveal her secret – that Boccanegra is her father – as Gabriele Adorno's family were killed by Boccanegra. Gabriele Adorno hides as Boccanegra is heard approaching. Amelia confesses to Boccanegra that she is in love with his enemy Gabriele Adorno. Boccanegra is angry, but tells Amelia that if Gabriele Adorno changes his ways, he may pardon him. Boccanegra asks Amelia to leave, then drinks the poisoned water, which Paolo Albiani has placed on the table, and falls asleep. Adorno emerges and is about to kill Boccanegra, when Amelia returns in time to stop him. Boccanegra wakes and reveals to Gabriele Adorno that Amelia is his daughter. Gabriele Adorno begs for Amelia's forgiveness (Trio: Perdon, Amelia... Indomito – "Forgive me, Amelia... A wild, / Jealous love was mine"). Noises of fighting are heard – Paolo Albiani has stirred up a revolution against Boccanegra. Gabriele Adorno promises to fight for Boccanegra, who vows that Adorno shall marry Amelia if he can crush the rebels. The Act 3 is set Inside the Doge's palace. The uprising against Boccanegra has been put down. Paolo Albiani has been condemned to death for fighting with the rebels against Boccanegra. Fiesco is released from prison by the Doge's men. On his way to the scaffold, Paolo Albiani boasts to Fiesco that he has poisoned Boccanegra. Fiesco is deeply shocked. Fiesco confronts Boccanegra, who is now dying from Paolo's poison. Boccanegra recognizes his old enemy and tells Fiesco that Amelia is his granddaughter. Fiesco feels great remorse and tells Boccanegra about the poison. Gabriele Adorno and Amelia, newly married, arrive to find the two men reconciled. Boccanegra tells Amelia that Fiesco is her grandfather and, before he dies, names Gabriele Adorno his successor.

The crowd mourns the death of Boccanegra. Roma Teatro dell'Opera, 8 settembre 1952 Giuseppe

Verdi - Simon Boccanegra. Mario Filippeschi nel ruolo di Gabriele Adorno

AGRIPPA. Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, Roman statesman and general. Samuel Barber: Antony and Cleopatra

EHENOBARBO. Gnaeus Domitius. Roman consul (32 BC). Samuel Barber: Antony and Cleopatra (as Enobarbus)

ALESSANDRO. Severo. Emperor of Rome. George Frideric Handel: Alessandro Severo

ALESSIO. Saint, of Rome. Stefano Landi: Sant'Alessio (1631; the first opera written on an historical subject.

D'ESTE. Alfonso I. Duke of Ferrara, husband of Lucrezia Borgia. Gaetano Donizetti: Lucrezia Borgia

D'ESTE. Alfonso II. Duke of Ferrara Gaetano Donizetti, "Torquato Tasso".

ALIGHIERI, Dante. Rachmaninov, "Francesca da Rimini". Italian poet Tan Dun: Marco Polo. Sergei Rachmaninoff: Francesca da Rimini

Amalasuntha, Queen of the Ostrogoths. André Messager: Isoline (as La Reine Amalasonthe)

ANNA. Of Bavaria, Holy Roman Empress, Queen of Rome and Bavaria. Ignaz Holzbauer: Günther von Schwarzburg.

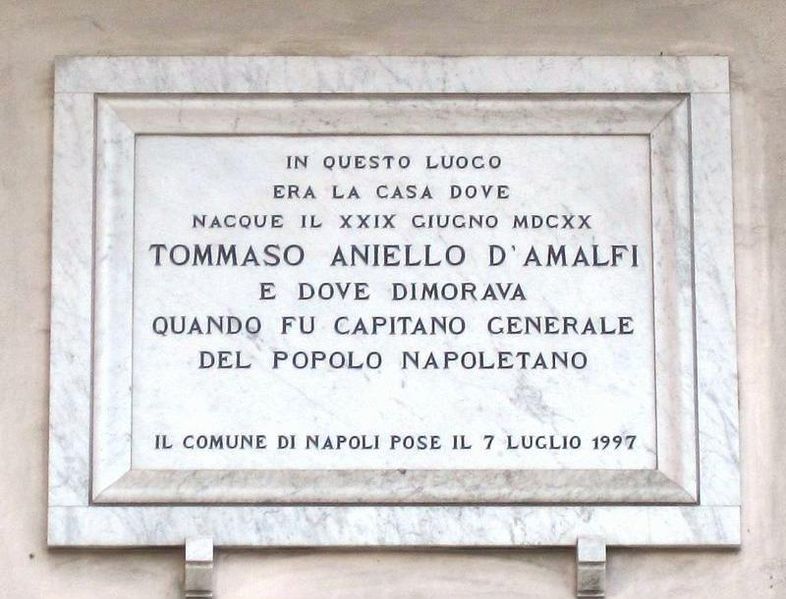

ANIELLO. Tommaso.

-- detto il "Masaniello". Neapolitan fisherman, revolutionary leader.

L'uccisione di Don Giuseppe Carafa. Dipinto di Micco Spadaro. Daniel Auber: La muette de Portici (aka Masaniello). Reinhard Keiser: Masagniello. Reinhard Keiser: Die neapolitanische Fischer-Empörung oder Masaniello furioso. Auber's opera is loosely based on the historical uprising of Masaniello against Spanish rule in Naples in 1647.

Act 1 [edit] We witness the wedding of Alfonso, son of the Viceroy of Naples, with the Spanish Princess Elvira. Alfonso, who has seduced Fenella, the Neapolitan Masaniello's mute sister and abandoned her, is tormented by doubts and remorse, fearing that she has committed suicide. During the festival Fenella rushes in to seek protection from the Viceroy, who has kept her a prisoner for the past month. She has escaped from her prison and narrates the story of her seduction by gestures, showing a scarf which her lover gave her. Elvira promises to protect her and proceeds to the altar, Fenella vainly trying to follow. In the chapel Fenella recognizes her seducer in the bridegroom of the Princess. When the newly married couple come out of the church, Elvira presents Fenella to her husband and discovers from the mute girl's gestures, that he was her faithless lover. Fenella flies, leaving Alfonso and Elvira in sorrow and despair. Act 2 [edit] The fishermen, who have been brooding in silence over the tyranny of their foes, begin to assemble. Pietro, Masaniello's friend, has sought for Fenella in vain, but at length she appears of her own accord and confesses her wrongs. Masaniello is infuriated and swears to have revenge, but Fenella, who still loves Alfonso, does not mention his name. Then Masaniello calls the fishermen to arms and they swear perdition to the enemy of their country. Act 3 [edit] The Naples marketplace. People go to and fro, selling and buying, all the while concealing their purpose under a show of merriment and carelessness. Selva, the officer of the Viceroy's body-guard, from whom Fenella has escaped, discovers her and the attempt to rearrest her is the sign for a general revolt, in which the people are victorious. Act 4 [edit]. Fenella comes to her brother's dwelling and describes the horrors, which are taking place in the town. The relation fills his noble soul with sorrow and disgust. When Fenella has retired to rest, Pietro enters with comrades and tries to excite Masaniello to further deeds, but he only wants liberty and shrinks from murder and cruelties. They tell him that Alfonso has escaped and that they are resolved to overtake and kill him. Fenella, who hears all, decides to save her lover. At this moment Alfonso begs at her door for a hiding-place. He enters with Elvira, and Fenella, though at first disposed to avenge herself on her rival, pardons her for Alfonso's sake. Masaniello, reentering, assures the strangers of his protection and even when Pietro denounces Alfonso as the Viceroy's son, he holds his promise sacred. Pietro with his fellow-conspirators leaves him full of rage and hatred. Meanwhile the magistrate of the city presents Masaniello with the Royal crown and he is proclaimed King of Naples. Act 5 [edit] Before the Viceroy's palace. In a gathering of fishermen, Pietro confides to Moreno that he has administered poison to Masaniello, in order to punish him for his treason, and that the King of one day will soon die. While he speaks, Borella rushes in to tell of a fresh troop of soldiers, marching against the people with Alfonso at their head. Knowing that Masaniello alone can save them, the fishermen entreat him to take the command of them once more and Masaniello, though deadly ill and half bereft of his reason, complies with their request. The combat takes place, while an eruption of Vesuvius is going on. Masaniello falls in the act of saving Elvira's life. On hearing these terrible tidings Fanella rushes to the terrace, from which she leaps into the abyss beneath, while the fugitive noblemen take again possession of the city. Bibliografia. Bartolommeo Capasso, La casa e la famiglia di Masaniello. Ricordi della storia e della vita napolitana, Napoli, Giannini Editore, 1919. Bartolommeo Capasso, Masaniello. La sua vita la sua rivoluzione, Napoli, Luca Torre, 1993. Giuseppe Campolieti, Masaniello. Trionfo e caduta del celebre capopopolo nello sfondo della tumultuosa Napoli del Seicento, Novara, Istituto geografico De Agostini, 1989. ISBN 88-402-0315-X Francesco Capecelatro, Diario di Francesco Capecelatro contenente la storia delle cose avvenute nel Reame di Napoli negli anni 1647-1650 vol. I, Napoli, Stabilimento Tipografico di Gaetano Nobile, 1850. URL consultato il 17-9-2008. Benedetto Croce, Storia del Regno di Napoli, Bari, Laterza, 1980. Silvana D'Alessio, Contagi. La rivolta napoletana del 1647-48: linguaggio e potere politico, Firenze, Centro Editoriale Toscano, 2003. ISBN 88-7957-213-X. Silvana D'Alessio, Masaniello. La sua vita e il suo mito in Europa, Salerno, Salerno Editrice, 2007. ISBN 88-8402-586-9. Eduardo De Filippo, Tommaso d'Amalfi, Torino, Einaudi, 1980. Tommaso de Santis, Storia del tumulto di Napoli, Trieste, Colombo Coen, 1858. URL consultato il 17-9-2008. Roberto De Simone; Thomas Asselijn; Christian Weise, Masaniello nella drammaturgia europea e nella iconografia del suo secolo, Gaetano Macchiaroli Editore, 1998. ISBN 88-85823-28-9. Salvatore Di Giacomo, Celebrità napoletane, Tranio, Vecchi, 1896. Vittorio Dini, Masaniello. L'eroe e il mito, Roma, Newton Compton, 1995. ISBN 88-7983-848-2. Ascanio Filomarino, Lettere in Francesco Palermo (a cura di), Narrazioni e documenti sulla storia del regno di Napoli dall'anno 1522 al 1667, Firenze, Giovan Pietro Vieusseux, 1846, pp. 379-393. URL consultato il 5-8-2008.. Mario Forgione, Masaniello. 7-16 Luglio 1647. Cronaca di dieci giorni rivoluzionari, Napoli, EDI, 1994. Alessandro Giraffi, Le rivolutioni di Napoli, Venezia, Filippo Alberto, 1648. URL consultato il 17-9-2008. Vittorio Gleijeses, La Storia di Napoli vol. II, Napoli, Società Editrice Napoletana, 1974. Ottorino Gurgo, Lazzari. Una storia napoletana, Napoli, Guida Editori, 2005. ISBN 88-7188-857-X URL consultato il 5-8-2008. Aurelio Musi, La rivolta di Masaniello nella scena politica barocca, Napoli, Guida Editori, 1989. ISBN 88-7188-586-4 URL consultato il 5-8-2008. Aurelio Musi, Protagonisti nella Storia di Napoli, Napoli, Elio De Rosa, 1994. Nicola Napolitano, Masaniello e Giulio Genoino. Mito e coscienza di una rivolta, Napoli, Fausto Fiorentino Editore, 1962. Gaetano Parente, Masaniello. Storia del Secolo XVII, Firenze, Vincenzo Batelli e Figli, 1838. URL consultato il 17-9-2008. Giovan Battista Piacente, Le rivoluzioni del Regno di Napoli negli anni 1647-1648 e l'assedio di Piombino e Portolongone, Napoli, Tipografia di Giuseppe Guerrera, 1861. URL consultato il 17-9-2008. Antonio Romano, Memorie di Tommaso Aniello d'Amalfi detto Masaniello. Responsabilità della Chiesa nella sconfitta della rivoluzione napoletana e guerra d'indipendenza, Napoli, Edizioni del Delfino, 1990. Michelangelo Schipa, La così detta rivoluzione di Masaniello: da memorie contemporanee inedite, Napoli, Pierro, 1918. Michelangelo Schipa, Giuseppe Galasso (a cura di), Studi masanielliani, Napoli, Società Napoletana di Storia Patria, 1997. ISBN 88-8044-045-4 (ristampa anastatica)

L'uccisione di Don Giuseppe Carafa. Dipinto di Micco Spadaro. Daniel Auber: La muette de Portici (aka Masaniello). Reinhard Keiser: Masagniello. Reinhard Keiser: Die neapolitanische Fischer-Empörung oder Masaniello furioso. Auber's opera is loosely based on the historical uprising of Masaniello against Spanish rule in Naples in 1647.

Act 1 [edit] We witness the wedding of Alfonso, son of the Viceroy of Naples, with the Spanish Princess Elvira. Alfonso, who has seduced Fenella, the Neapolitan Masaniello's mute sister and abandoned her, is tormented by doubts and remorse, fearing that she has committed suicide. During the festival Fenella rushes in to seek protection from the Viceroy, who has kept her a prisoner for the past month. She has escaped from her prison and narrates the story of her seduction by gestures, showing a scarf which her lover gave her. Elvira promises to protect her and proceeds to the altar, Fenella vainly trying to follow. In the chapel Fenella recognizes her seducer in the bridegroom of the Princess. When the newly married couple come out of the church, Elvira presents Fenella to her husband and discovers from the mute girl's gestures, that he was her faithless lover. Fenella flies, leaving Alfonso and Elvira in sorrow and despair. Act 2 [edit] The fishermen, who have been brooding in silence over the tyranny of their foes, begin to assemble. Pietro, Masaniello's friend, has sought for Fenella in vain, but at length she appears of her own accord and confesses her wrongs. Masaniello is infuriated and swears to have revenge, but Fenella, who still loves Alfonso, does not mention his name. Then Masaniello calls the fishermen to arms and they swear perdition to the enemy of their country. Act 3 [edit] The Naples marketplace. People go to and fro, selling and buying, all the while concealing their purpose under a show of merriment and carelessness. Selva, the officer of the Viceroy's body-guard, from whom Fenella has escaped, discovers her and the attempt to rearrest her is the sign for a general revolt, in which the people are victorious. Act 4 [edit]. Fenella comes to her brother's dwelling and describes the horrors, which are taking place in the town. The relation fills his noble soul with sorrow and disgust. When Fenella has retired to rest, Pietro enters with comrades and tries to excite Masaniello to further deeds, but he only wants liberty and shrinks from murder and cruelties. They tell him that Alfonso has escaped and that they are resolved to overtake and kill him. Fenella, who hears all, decides to save her lover. At this moment Alfonso begs at her door for a hiding-place. He enters with Elvira, and Fenella, though at first disposed to avenge herself on her rival, pardons her for Alfonso's sake. Masaniello, reentering, assures the strangers of his protection and even when Pietro denounces Alfonso as the Viceroy's son, he holds his promise sacred. Pietro with his fellow-conspirators leaves him full of rage and hatred. Meanwhile the magistrate of the city presents Masaniello with the Royal crown and he is proclaimed King of Naples. Act 5 [edit] Before the Viceroy's palace. In a gathering of fishermen, Pietro confides to Moreno that he has administered poison to Masaniello, in order to punish him for his treason, and that the King of one day will soon die. While he speaks, Borella rushes in to tell of a fresh troop of soldiers, marching against the people with Alfonso at their head. Knowing that Masaniello alone can save them, the fishermen entreat him to take the command of them once more and Masaniello, though deadly ill and half bereft of his reason, complies with their request. The combat takes place, while an eruption of Vesuvius is going on. Masaniello falls in the act of saving Elvira's life. On hearing these terrible tidings Fanella rushes to the terrace, from which she leaps into the abyss beneath, while the fugitive noblemen take again possession of the city. Bibliografia. Bartolommeo Capasso, La casa e la famiglia di Masaniello. Ricordi della storia e della vita napolitana, Napoli, Giannini Editore, 1919. Bartolommeo Capasso, Masaniello. La sua vita la sua rivoluzione, Napoli, Luca Torre, 1993. Giuseppe Campolieti, Masaniello. Trionfo e caduta del celebre capopopolo nello sfondo della tumultuosa Napoli del Seicento, Novara, Istituto geografico De Agostini, 1989. ISBN 88-402-0315-X Francesco Capecelatro, Diario di Francesco Capecelatro contenente la storia delle cose avvenute nel Reame di Napoli negli anni 1647-1650 vol. I, Napoli, Stabilimento Tipografico di Gaetano Nobile, 1850. URL consultato il 17-9-2008. Benedetto Croce, Storia del Regno di Napoli, Bari, Laterza, 1980. Silvana D'Alessio, Contagi. La rivolta napoletana del 1647-48: linguaggio e potere politico, Firenze, Centro Editoriale Toscano, 2003. ISBN 88-7957-213-X. Silvana D'Alessio, Masaniello. La sua vita e il suo mito in Europa, Salerno, Salerno Editrice, 2007. ISBN 88-8402-586-9. Eduardo De Filippo, Tommaso d'Amalfi, Torino, Einaudi, 1980. Tommaso de Santis, Storia del tumulto di Napoli, Trieste, Colombo Coen, 1858. URL consultato il 17-9-2008. Roberto De Simone; Thomas Asselijn; Christian Weise, Masaniello nella drammaturgia europea e nella iconografia del suo secolo, Gaetano Macchiaroli Editore, 1998. ISBN 88-85823-28-9. Salvatore Di Giacomo, Celebrità napoletane, Tranio, Vecchi, 1896. Vittorio Dini, Masaniello. L'eroe e il mito, Roma, Newton Compton, 1995. ISBN 88-7983-848-2. Ascanio Filomarino, Lettere in Francesco Palermo (a cura di), Narrazioni e documenti sulla storia del regno di Napoli dall'anno 1522 al 1667, Firenze, Giovan Pietro Vieusseux, 1846, pp. 379-393. URL consultato il 5-8-2008.. Mario Forgione, Masaniello. 7-16 Luglio 1647. Cronaca di dieci giorni rivoluzionari, Napoli, EDI, 1994. Alessandro Giraffi, Le rivolutioni di Napoli, Venezia, Filippo Alberto, 1648. URL consultato il 17-9-2008. Vittorio Gleijeses, La Storia di Napoli vol. II, Napoli, Società Editrice Napoletana, 1974. Ottorino Gurgo, Lazzari. Una storia napoletana, Napoli, Guida Editori, 2005. ISBN 88-7188-857-X URL consultato il 5-8-2008. Aurelio Musi, La rivolta di Masaniello nella scena politica barocca, Napoli, Guida Editori, 1989. ISBN 88-7188-586-4 URL consultato il 5-8-2008. Aurelio Musi, Protagonisti nella Storia di Napoli, Napoli, Elio De Rosa, 1994. Nicola Napolitano, Masaniello e Giulio Genoino. Mito e coscienza di una rivolta, Napoli, Fausto Fiorentino Editore, 1962. Gaetano Parente, Masaniello. Storia del Secolo XVII, Firenze, Vincenzo Batelli e Figli, 1838. URL consultato il 17-9-2008. Giovan Battista Piacente, Le rivoluzioni del Regno di Napoli negli anni 1647-1648 e l'assedio di Piombino e Portolongone, Napoli, Tipografia di Giuseppe Guerrera, 1861. URL consultato il 17-9-2008. Antonio Romano, Memorie di Tommaso Aniello d'Amalfi detto Masaniello. Responsabilità della Chiesa nella sconfitta della rivoluzione napoletana e guerra d'indipendenza, Napoli, Edizioni del Delfino, 1990. Michelangelo Schipa, La così detta rivoluzione di Masaniello: da memorie contemporanee inedite, Napoli, Pierro, 1918. Michelangelo Schipa, Giuseppe Galasso (a cura di), Studi masanielliani, Napoli, Società Napoletana di Storia Patria, 1997. ISBN 88-8044-045-4 (ristampa anastatica)

ANNIBALE. Carthaginian ruler.

Johann Adolf Hasse, Domènec Terradellas, Giovanni Battista Lampugnani and Pietro Domenico Paradie, "Annibale in Capua".

ARMINIO. Germanic chieftain. George Frideric Handel: Arminio.

ARRIGO. Guerriero veronese alla battaglia di Legnano. The Battle of Legnano was fought on May 29, 1176, between the forces of the Holy Roman Empire, led by Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, and the Lombard League.

The tenor role in Verdi's "La Battaglia di Legnano". Personaggi: Federico Barbarossa ( basso), i due consoli (bassi), il podestà di Como (basso), Rolando, duce milanese (baritono), Lida, sua moglie (soprano), Arrigo, guerriero veronese (tenore) Marcovaldo, prigioniero alemanno (baritono), Imelda, ancella di Lidia (mezzosoprano) Uno scudiero di Arrigo (tenore). Un araldo (tenore).

ARRIGO. The tenor role in Verdi's, "I Vespri Siciliani". I Vespri siciliani sono un evento storico avvenuto nella Sicilia del XIII secolo. Secondo la tradizione, la rivoluzione del Vespro fu organizzata in gran segreto dai principali esponenti della nobiltà siciliana. Quattro furono i principali organizzatori: Giovanni da Procida, della famosa Scuola medica salernitana, medico di Federico II; Alaimo di Lentini, Signore di Lentini; Gualtiero di Caltagirone, Barone, Signore di Caltagirone; e Palmiero Abate, Signore di Trapani e Conte di Butera.

Guido di Monteforte, governor of Sicily under Charles d'Anjou, king of Naples. Lord of Bethune, le sire -- a French officer. Conte di Vaudemont, a French officer. ARRIGO, un siciliano. Giovanni da Procida, dottore. La duchessa Elena, sorella del Duca Frederico d'Austria. Bibliografia: Steven Runciman (1958), I vespri siciliani, 1997, Edizioni Dedalo. Leonardo Bruni (1416), History of the Florentine People, Harvard, 2001. ISBN 0-674-00506-6. "Sicilian Vespers" in Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Santi Correnti, «Il Vespro» Giovanni Battista Niccolini (1882), Vespro Siciliano: storia inedita, per cura di Corrado Gargiolli. Pubblicato da D. G. Brigola. Francesco Benigno e Giuseppe Giarrizzo, Storia della Sicilia, vol. 3, ed. Laterza, Roma-Bari, 1999. ISBN 88-421-0535-X

ASTORGA Emanuele d'. Italian composer. Johann Joseph Abert: Astorga

ATTILA the Hun. Giuseppe Verdi: Attila.

AUGUSTO. Cesare Augusto. Roman Emperor. Samuel Barber: Antony and Cleopatra (as Octavius Caesar)

AURELIANO. Emperor of Rome. Gioachino Rossini: Aureliano in Palmira

************************ B **********************************

BARBERINI. Maffeo. Pope Urban VIII. Philip Glass, "Galileo Galilei". The pope appears as both Cardinal Maffeo Barberini and Pope Urban VIII.

BOCCACCIO, Giovanni. Italian writer, poet. Franz von Suppé: Boccaccio

BOCCANEGRA. Simone, first Doge of Genoa. Giuseppe Verdi: Simon Boccanegra

BONAPARTE, Carolina. -- Queen Consort of Naples and Sicily, sister of Napoleon. Pauline Bonaparte, Princess of France, sister of Napoleon. Ivan Caryll, "The Duchess of Dantzic".

BORGIA, Cesare. Figlio di Rodrigo Borgia (papa Alessandro VI), fratello (e amante) di Lucrezia Borgia.

Leoncavallo: "Cesare Borgia": terza parte della trilogia rinascimentale: "Il creposcolo".

BORGIA. Saint Francis -- 4th Duke of Gandía, Spanish Superior-General of the Jesuits

Ernst Krenek: Karl V

BORGIA. Lucrezia. -- Daughter of Pope Alexander VI.

Gaetano Donizetti, "Lucrezia Borgia".

BORROMEO. Saint Charles. Italian cardinal. Hans Pfitzner: Palestrina

BROGNI, Gian Francesco. Italian cardinal Fromental Halévy: La Juive

BRUTO. Marcus Junius Brutus the Younger, Roman politician, co-assassin of Julius Caesar. Giselher Klebe: Die Ermordung Cäsars

*************** C ******************

CAGLIOSTRO, Alessandro. Alessandro Cagliostro (Giuseppe Balsamo), Italian adventurer and imposter. Johann Strauss II: Cagliostro in Wien. Mikael Tariverdiev: Graf Cagliostro

CARUSO, Enrico. Enrico Caruso, Italian tenor. Edwin Penhorwood: Too Many Sopranos (spoofed as "Enrico Carouser")

CASANOVA, Giacomo. Italian adventurer and libertine. Dominick Argento: Casanova's Homecoming. Albert Lortzing: Casanova

CASCA, Servilius, co-assassin of Julius Caesar

CASSIO, Gaius Longinus, Roman politician, co-assassin of Julius Caesar. Giselher Klebe: Die Ermordung Cäsars

CAVALCANTI. Guido. Florentine poet. Ezra Pound and George Antheil: Cavalcanti

CELLINI, Benvenuto Italian sculptor, goldsmith, artisan Hector Berlioz: Benvenuto Cellini

CENCI, Beatrice. Italian noblewoman, protagonist of a famous murder trial. Havergal Brian: The Cenci (1951–52). Alberto Ginastera: Beatrix Cenci. Berthold Goldschmidt: Beatrice Cenci. Alessandro Londei e Brunella Caronti: Beatrice Cenci (2006). James Rolfe: Beatrice Chancy

CHAUCER, Geoffrey Chaucer, English author, poet, philosopher, courtier and diplomat

Reginald De Koven: The Canterbury Pilgrims

CIMBER. Tillius Cimber, co-assassin of Julius Caesar Giselher Klebe: Die Ermordung Cäsars (as Metellus Cimber)

CINNA. Helvius Cinna, Roman poet. Lorenzo Ferrero: Le piccole storie – ai margini delle guerre

Giselher Klebe: Die Ermordung Cäsars

CINNA. Lucius Cornelius Cinna, Roman consul. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Lucio Silla

CLAUDIO. Emperor Claudius of Rome. George Frideric Handel: Agrippina

CLEMENTE VII. Papa. Hector Berlioz: Benvenuto Cellini. Ernst Krenek: Karl V

CLEOPATRA. Cleopatra VII, Pharaoh of Egypt. Samuel Barber: Antony and Cleopatra

Domenico Cimarosa: La Cleopatra. Carl Heinrich Graun: Cesare e Cleopatra. Louis Gruenberg: Antony and Cleopatra. Henry Kimball Hadley: Cleopatra's Night. George Frideric Handel: Giulio Cesare (in Egitto). Felip Pedrell: Cléopâtre. Jules Massenet: Cléopâtre

CLELIA. early Roman figure, possibly legendary. Filippo Amadei, Giovanni Battista Bononcini and George Frideric Handel: Muzio Scevola

COCLES. Horatius Cocles, Roman military officer. Filippo Amadei, Giovanni Battista Bononcini and George Frideric Handel: Muzio Scevola

COLLATINO Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, Roman consul, husband of Lucretia. Benjamin Britten: The Rape of Lucretia

COLONNA. Stefano Colonna (1265–1348), Roman political figure. Richard Wagner: Rienzi

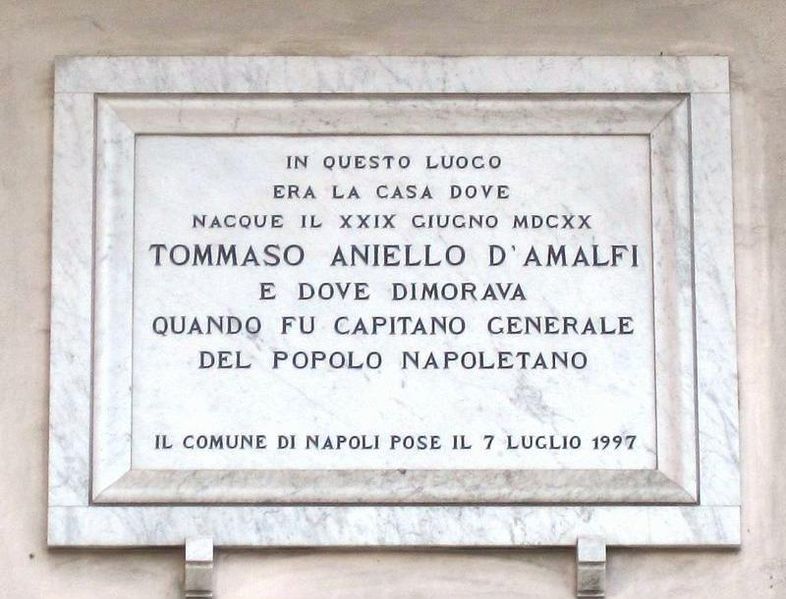

COLOMBO. Christopher, Genoese explorer of the New World.

Born in Genova.

COSTANTINO I. Emperor Constantine I "The Great" of Rome. Gaetano Donizetti: Fausta

CORIOLANO. Gaius Marcius Coriolanus, legendary Roman leader. Francesco Cavalli: Coriolano

CORNARO, Giorgio Cornaro, Italian nobleman, father of Catherine Cornaro. Gaetano Donizetti: Caterina Cornaro (as Andrea Cornaro)

CRASSO. Marcus Licinius Crassus, Roman general and politician. Francesco Cavalli: Pompeo Magno.

CRISPO. Flavius Julius Crispus, Caesar of the Roman Empire. Gaetano Donizetti: Fausta

---- D ----

DIOCLEZIANO. Emperor Diocletian of Rome. Henry Purcell: Dioclesian

DOLABELLA. Publius Cornelius Dolabella, Roman general. Samuel Barber: Antony and Cleopatra

---- E ----

ELIOGABALO Emperor Elagabalus of Rome (Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus). Francesco Cavalli: Eliogabalo. Pietro Simone Agostini: Eliogabalo

FARNESE. Elisabeth Farnese, Queen Consort to Philip V of Spain. John Barnett: Farinelli

ENZIO. Enzio of Sardinia, king of Sardinia. Johann Joseph Abert: König Enzio and Enzio von Hohenstaufen (2nd version)

EZIO. Flavio. Roman general Giuseppe Gazzaniga: Ezio. George Frideric Handel: Ezio. Gaetano Latilla: Ezio. Giuseppe Verdi: Attila

---- F -----

FALIERO, Marino. Doge of Venice. Gaetano Donizetti: Marino Faliero

FARINELLI. Farinelli, Italian castrato singer. Daniel Auber: La part du diable (or Carlo Broschi) (as Carlo Broschi). John Barnett: Farinelli

FAUSTA. Fausta Flavia Maxima, Empress of Rome, second wife of Constantine the Great

Gaetano Donizetti: Fausta

FOSCARI. Francesco Foscari, Doge of Venice. Giuseppe Verdi: I due Foscari

Fouché, Joseph. Duke of Otranto. Umberto Giordano: Madame Sans-Gêne

MALATESTA, Paolo, conte di Ghiaggiuolo. Francesca da Rimini, contemporary and literary subject of Dante. Emil Ábrányi: Paola és Francesca. Emanuele Borgatta: Francesca da Rimini. Paolo Carlini: Francesca da Rimini. Fournier-Gorre: Francesca da Rimini. Pietro Generali: Francesca da Rimini. Hermann Goetz: Francesca da Rimini. Franco Leoni: Francesca da Rimini. Gioacchino Maglioni: Francesca da Rimini Luigi Mancinelli: Paolo e Francesca. Saverio Mercadante: Francesca da Rimini. Francesco Morlacchi: Francesca da Rimini. Eugene Nordal: Francesca da Rimini. Salvatore Papparlado: Francesca da Rimini. Gaetano Quilici: Francesca da Rimini. Sergei Rachmaninoff: Francesca da Rimini (as Francesca Malatesta). Giuseppe Staffa: Francesca da Rimini. Feliciano Strepponi: Francesca da Rimini. Antonio Tamburini: Francesca da Rimini. Ambroise Thomas: Francesca da Rimini. Riccardo Zandonai: Francesca da Rimini. Alfredo Aracil: Francesca o El infierno de los enamorados.

FRANCESCO. Saint Francis of Assisi, founder of the Franciscans. Olivier Messiaen: Saint François d'Assise

BARBAROSSA. Frederick I "Barbarossa", Holy Roman Emperor. Giuseppe Verdi: La battaglia di Legnano

---- G -----

GABRINI, Niccola. Cola di Rienzo, son of Lorenzo Gabrini. Cola's father's forename was shortened from "Lorenzo" to "Rienzo". His own forname, "Nicola," was shortened to "Cola". Hence the Cola di Rienzo, or Rienzi, by which he is generally known. RIENZI. Cola di Rienzo, Roman tribune. Richard Wagner: Rienzi Cola di Rienzo, al secolo Nicola di Lorenzo Gabrini o in romanesco Cola de Rienzi (Roma, 1313 – Roma, 8 ottobre 1354), tribuno, divenne noto perché tentò, nel periodo finale del medioevo, di restaurare il comune nella città di Roma straziata dai conflitti tra papi e baroni. Si autodefiniva "l'ultimo dei tribuni del popolo". Alla sua figura il compositore Richard Wagner ha dedicato l'opera lirica Rienzi, l'ultimo dei tribuni. L'8 ottobre 1354, un suo capitano che aveva destituito sollevò il popolo e lo condusse a Campidoglio. Là Cola, abbandonato da tutti i suoi, tentò per l'ultima volta di arringare i romani, che risposero dando fuoco alle porte. Cola allora cercò di scampare travestendosi da popolano pezzente, alterando anche la voce. Ma fu riconosciuto dai braccialetti che non si era tolto («Erano 'naorati: non pareva opera de riballo»), smascherato e condotto in una sala per essere giudicato. «Là addutto, fu fatto uno silenzio. Nullo uomo era ardito toccarelo», finché un popolano «impuinao mano ad uno stocco e deoli nello ventre.» Gli altri seguirono, ad infierire, ma Cola era già morto. Il cadavere fu trascinato fino a San Marcello in via Lata, di fronte alle case dei Colonna, e lì lasciato appeso per due giorni e una notte. Il terzo giorno fu trascinato a Ripetta, presso il Mausoleo di Augusto, che era sempre un territorio dei Colonna, lì bruciato (commenta l'Anonimo: «Era grasso. Per la moita grassezza da sé ardeva volentieri»), e le ceneri disperse. His latter term of office was destined to be even shorter than his former one. Having vainly besieged the fortress of Palestrina, Cola returned to Rome, where he treacherously seized the soldier of fortune, Giovanni Moriale, who was put to death, and where, by other cruel and arbitrary deeds, he soon lost the favour of the people. Their passions were quickly aroused and a tumult broke out on 8 October. Cola attempted to address them, but the building in which he stood was set on fire, and while trying to escape in disguise he was murdered by the mob. The doors of the capitol were destroyed with axes and with fire. And while the senator attempted to escape in a plebeian garb, he was dragged to the platform of his palace, the fatal scene of his judgments and executions. After enduring the protracted tortures of suspense and insult, he was pierced with a thousand daggers, amidst the execrations of the people. Bibliografia: Anonimo romano, Cronica, Adelphi 1981 e 1991 (cap. XVIII e XXVII) la vita di Cola di Rienzo nella Cronica (testo) Ferdinand Gregorovius, Storia della città di Roma nel Medioevo, Einaudi 1973 (libro XI, capp. V, VI, VII) Tommaso di Carpegna Falconieri, Cola di Rienzo, Roma, Salerno Editrice, 2002, ISBN 88-8402-387-4 Ronald G. Musto, Apocalypse in Rome. Cola di Rienzo and the Politics of the New Age, Berkeley & Los Angeles, University of California Press, 2003, 436 pp

GALILEI, Galileo. Italian scientist. Philip Glass: Galileo Galilei

GALLA. Placidia, Roman regent, daughter of Emperor Theodosius I. Jaume Pahissa i Jo: Gal·la Placídia (1913)

GARIBALDI. Giuseppe. Italian freedom fighter. Gavin Bryars, Philip Glass and others: The Civil Wars: A Tree Is Best Measured When It Is Down.

GESUALDO. Carlo. Italian composer and murderer. Alfred Schnittke: Gesualdo

GIOCONDO. Lisa del Giocondo, Italian woman, subject of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa

Max von Schillings: Mona Lisa (as Mona Fiordalisa).

GIOVANNA I. of Naples, Queen of Naples. Juan Manén: Giovanna di Napoli.

GIULIA Caesaris, daughter of Julius Caesar, 4th wife of Pompey the Great

Francesco Cavalli: Pompeo Magno

GIULIANO, Salvatore. Salvatore Giuliano, Sicilian peasant. Lorenzo Ferrero, "Salvatore Giuliano."

GIULIANO. Salvatore. Lorenzo Ferrero, "Salvatore Giuliano". Set in Sicily, the story is based on the life of the legendary historical figure Salvatore Giuliano (1922-1950), a Sicilian peasant who fought the Italian authorities in the name of a separatist movement. Place: Western Sicily, Montelepre and surrounding mountain. Time: The second half of the 1940s. In an empty village at dawn a shot is heard and there is a glimpse of a man running. When the village awakes a representative of EVIS, the Volunteer Army for the Independence of Sicily, arrives to address the inhabitants and to introduce Salvatore Giuliano to them. In his speech, the man incites the villagers to endorse EVIS' fight for independence. After pledging his support to the cause, Giuliano remains alone with his lieutenant, Gaspare Pisciotta. They are discussing how to liberate Giuliano's mother from prison when, unexpectedly, she returns to him escorted by a Mafioso. Giuliano realizes that he has contracted a debt with the Mafia. In his mountain stronghold, Giuliano relates his life story to Maria, a Swedish journalist who came to interview him. He recalls that he became a bandit by chance, due to poverty and the injustice of the Italian state. He confesses that he hopes for a pardon and emigration to America. The interview is interrupted by the Mafioso who returned to claim his dues. He asks Giuliano to attack the communists' Labour Day parade at Portella della Ginestra in exchange for Mafia protection and help with his request for amnesty. Giuliano agrees. After the massacre, Colonel Ugo Luca, the head of the newly formed special police force for the suppression of banditry, is joined in the village square by a deputy who brings the minister's order to liquidate Giuliano because by now he knows too much. In the meantime, at his sister's wedding reception Giuliano carries out an irreparable act and executes five Mafiosi, who came to inform him that a reward for his capture has been set by the authorities in Rome. Appalled by this crime, the Mafioso meets Colonel Luca at Portella, and while the police are carrying away the corpses, they agree to unite their forces against Giuliano. Pisciotta is summoned to the Colonel, who succeeds in convincing him to betray Giuliano, in exchange for his own life. In a desperate final attempt, Pisciotta tries to persuade Giuliano to escape but he refuses to leave. In the empty village, as in the beginning, the shadows of two men appear on the background: one shoots and the other falls. The village lights go out and the voice of a woman is heard calling: "Giuliano!"

GIULIO CESARE. Julius Caesar, Consul and Dictator of Rome. Francesco Cavalli: Pompeo Magno

Carl Heinrich Graun: Cesare e Cleopatra. George Frideric Handel: Giulio Cesare (in Egitto). Giselher Klebe: Die Ermordung Cäsars. Antonio Sartorio: Giulio Cesare in Egitto

GOFFREDO. Godfrey of Bouillon, Frankish knight, leader of the First Crusade. George Frideric Handel: Rinaldo (as Goffredo)

GORETTI. St Maria Goretti, 20th century Catholic martyr. Marcel Delannoy: Maria Goretti, radiophonic opera

GRAMSCI. Antonio Gramsci, Italian political theorist. Luigi Nono: Al gran sole carico d'amore

GUICCIOLI. Teresa, Contessa Guiccioli, Italian mistress of Lord Byron. Virgil Thomson: Lord Byron

---- H -----

HAMILTON. Emma, Lady. English mistress of Horatio, Lord Nelson. Sir William Hamilton, British diplomat, husband of Emma, Lady Hamilton. Lennox Berkeley: Nelson

GISCO. Hasdrubal Gisco, Carthaginian general. Francesco Cavalli: Scipione affricano

ISSICRATEA. Queen Hypsicratea of Pontus, consort of Mithradates VI. Francesco Cavalli: Pompeo Magno (as Issicratea). Alessandro Scarlatti: Mitridate Eupatore

--- L ---

LASCARIS. Beatrice di Tenda.

Caterina Beatrice Lascaris di Ventimiglia e Tenda, detta "Beatrice di Tenda" (nata a Tenda, 1372 – Binasco, 13 settembre 1418), figlia del conte di Tenda Pietro Lascaris e di donna Poligena, discendeva da un ramo della famiglia imperiale bizantina dei Lascaris tramite Eudossia Lascaris figlia di Teodoro II Lascaris, imperatore di Nicea, e moglie di Guglielmo Pietro I di Ventimiglia, capostipite del ramo ligure della famiglia Lascaris di Ventimiglia (XIII secolo). Caterina Beatrice sposò in prime nozze il condottiero Facino Cane che la rapì dal castello paterno, portandola con sé nelle sue imprese guerresche, nelle quali Beatrice si dimostrò piuttosto partecipe e battagliera.

Seppe anche rivestire il ruolo di pacata consigliera durante la lotta di Cane per la conquista del potere sul ducato di Milano. Dopo essere rimasta vedova, nel 1412, si risposò con il duca di Milano Filippo Maria VISCONTI, portando in dote quattromila ducati d'oro e alcuni importanti territori piemontesi. Il matrimonio era stato imposto da Cane, che, lasciando il proprio patrimonio al Visconti, aveva posto come condizione che questi ne sposasse la vedova. Figura: La targa posta nel 1869 sulle mura del Castello di Binasco per ricordare il delitto del 1418 Nel 1418, probabilmente allo scopo di sottrarle gli ingenti beni, fu accusata dal marito di adulterio con un domestico, tale Michele Orombelli. Dopo aver confessato sotto tortura venne condannata a morte e decapitata nel castello di Binasco, insieme al suo presunto amante, il 13 settembre 1418. Il piano fu ordito, secondo alcuni, con la complicità della nobildonna Agnese del Maino, dama di compagnia di Beatrice e amante del marito Filippo. Sembra inoltre che il marito non sopportasse Beatrice a causa del carattere forte ed invasivo della donna, che trattava il duca quasi alla stregua di un precettore. Secondo la tradizione popolare Beatrice non si era resa responsabile di alcun tradimento, ma questo non impedì a Filippo di essere salutato con grande cortesia dal papa Martino V - allora suo alleato nell'interesse reciproco di espandere i propri domini nell'Italia centrosettentrionale - quando il pontefice passò da Milano quell'anno stesso. Alla sua vita si ispira il melodramma di Vincenzo Bellini del 1833 Beatrice di Tenda, tratto a sua volta dal libro omonimo del 1825 di Carlo Tedaldi Fores. « Quando suo marito Facino Cane morì, Filippo Maria Visconti, che era 20 anni più giovane di lei, la sposò per impadronirsi delle ricchezze dei Cane. Ben presto però fu pretestuosamente accusata ingiustamente di adulterio e decapitata, assieme al presunto amante. Questa drammatica vicenda venne portata in musica da Vincenzo Bellini » (Piero Cocconi). Il 13 giugno 1869 il comune di Binasco ha dedicato questa lapide monumentale in memoria di Beatrice di Tenda nel proprio Castello: « CON TURPE SCONOSCENZA RICAMBIANDO LA ILLIBATA FEDE L'ASSECURATO TRONO FILIPPO MARIA VISCONTI

SPEGNEVA NELLA NOTTE DEL 13 SETTEMBRE 1418 IN QUESTE MURA L'ONORANDA CONSORTE BEATRICE DI TENDA L'ORRORE DEL FATTO FECONDI E RITEMPRI NE' FIGLI D'ITALIA GLI AFFETTI PIÙ PURI I DOVERI PIÙ SACRI AUSPICE IL MUNICIPIO ALCUNI OBLATORI POSERO IL 13 GIUGNO 1869 Lo Storico del Comune Damiano Muoni scrisse » Inoltre le sono state dedicate alcune vie (una a Binasco) soprattutto in val Roia. Opere letterarie. Diodata Roero Saluzzo, Il Castello di Binasco, Firenze, della Tipografia e Calcografia Goldoniana, 1824. Carlo Tedaldi Fores, Beatrice di Tenda Tragedia Istorica, Milano, della Società Tipogr. de' Classici Italiani, 1825. Pietro Marocco, Il Castello di Binasco, Milano, Felice Rusconi, 1829. Giambattista Bazzoni, Racconti Storici : Macaruffo Venturiero o La Corte del Duca Filippo Maria Visconti, Milano, Presso Omobono Manini, 1832. Eugenio Mastrozzi, Il Pellegrino di Binasco Scene della Storia Milanese, Pavia, Tipografia Fusi e Comp., 1844. Felice Turotti, Beatrice di Tenda, Milano, Borroni e Scotti, 1845. Damiano Muoni, Binasco ed altri comuni dell'agro milanese, Milano, Già Boniotti, 1864. Inaugurazione a Binasco della lapide monumentale a Beatrice di Tenda, Milano, Tip. Letteraria, 1869. G. C., Beatrice di Tenda Racconto Storico del Professore G. C., Codogno, Tipografia Cairo, 1885. Note [modifica] ^ La Battaglia di Borgomanero sul sito del comune di Borgomanero (No) ^ A. Manzoni, Opere scelte vol.1, ed. Passigli, 1832, p. 344 ^ P. C. Decembrio, Vita di Filippo Maria Visconti, Milano 1983, p. 79 ^ N. Capponi, La battaglia di Anghiari, Milano 2011, pp. 33-34 Collegamenti esterni [modifica] (FR) Jean Galliani, Lascaris di Ventimiglia, in Généalogie des familles nobles Controllo di autorità VIAF: 50573713 Portale Biografie Portale Medioevo Portale Storia. Categorie: Nati nel 1372, Morti nel 1418, Morti il 13 settembre

Nati a Tenda (Francia), Morti a Binasco, Persone giustiziate per decapitazione, Ventimiglia (famiglia) | [altre]. Opera Bellini.

LASCARIS, Beatrice, di TENDA. Beatrice di Tenda, Italian noblewoman. Vincenzo Bellini: Beatrice di Tenda. Bellini's opera is the story of the woman who was the widow of the condottiere Facino Cane and later the wife of Duke Filippo Maria Visconti, in 15th century Milan. Visconti has grown tired of Beatrice. Beatrice regrets her impetuous marriage to him after her first husband's death, a marriage that has delivered her and her people into the Duke's tyrannical power. Time: 1418 Place: The Castle of Binasco, near Milan[1] Act 1. Filippo attends a ball at the Castle Binasco in Italy, shadowed as usual by the sinister Rizzardo. He is fed up with everyone paying obeisance to his wife. His sycophantic courtiers tell him how much they sympathize, and suggest that Beatrice's servants are all plotting against him. Beautiful harp music is heard. Agnese, the current object of Filippo's lust, sings from afar that life is empty without love. Filippo echoes her thoughts and states how much he loves her; she has no equal. His courtiers again sympathize with him and encourage him to seize the moment. Agnese disappears and all leave. Then Agnese reappears, this time singing for Orombello. Mysteriously, she wishes that her heart will guide him to her arms and, as in all good opera plots, the object of her lust makes his entrance. Orombello splutters that he does not know where he is or why he is there. Comforted by Agnese, he begins to relax and agrees that he is deeply in love and, when asked about a letter, shows her the one he is carrying. "Such misfortune!" The letter he is referring to is one of many he has written to Beatrice and not the one that Agnese had sent to him. Agnese's world falls apart, her tenderness turns to vitriol, and the two of them spit out a dramatic aria and leave.

Beatrice enters one of her secret places with her ladies. She is happy, but soon loses her poise and laments how misguided she has been to have married the evil Duke Filippo. As they all go to leave, Filippo sees them in the distance and, believing she is avoiding him, demands that she be brought back. The two of them accuse and rage at each other, with Filippo producing some secret papers stolen from Beatrice's apartment.

In another scene, slightly the worse for wear, Filippo's soldiers discuss his silence and temper. Beatrice enters carrying a portrait of her beloved, deceased husband, Facino. She is bemoaning the fact that everyone has abandoned her when Orombello enters protesting that he has not. Excitedly, he tells her his plans to rally the troops and help her free herself. She crushes him saying, in so many words, that she does not rate his expertise in security matters. Stunned, Orombello protests his love and, even when begged to do so, will not leave her presence; instead, he kneels down in front of her, at which moment Agnese and Filippo enter and accuse the two traitors of having an affair. Everyone now joins in with accusation, counter accusation, attack and defence. The upshot is that Filippo has the pair arrested — to be tried in Court for adultery.

[edit] Act 2

The courtiers learn of the terrible torture that has been applied to Orombello. Then, the Court is summoned and Filippo sets out the case for the prosecution. Beatrice is dragged in, and she protests that the Court has no jurisdiction. Next, Orombello is hauled in and, after desperately seeking forgiveness from Beatrice, proclaims her innocence. Beatrice regains her will to live and something in her speaking touches Filippo's heart. He announces that the sentence should be delayed. The Court overrules him stating that more torture should be applied until the truth is spoken. Again, Filippo changes his mind and, supporting the Court's decision, instructs that, indeed, more torture seems to be necessary to extract the truth. The Court rises.Filippo and Agnese, full of remorse, are left alone and Agnese, realizing that things have gone much further than she had expected, begs Filippo to drop all the charges; but Filippo, not wishing to look weak, dismisses the idea.

Filippo now goes through several stages of torment and is obviously still deeply in love with Beatrice. Just as he has made up his mind to drop all the charges, with cruel timing, men still loyal to the late condottiere Facino arrive, to invade the castle. As a result, Filippo signs the death warrant now handed to him by Anichino* and tries to justify his actions to the crowd, blaming Beatrice's behaviour.

There is a scene in which we see Beatrice's ladies outside Orombello's cell, while Beatrice prays. The action reaches its finale.

LEONE. Pope St Leo I "The Great". Giuseppe Verdi: Attila (as Leone)

LEONE. Brother Leo, friend and confidant of Francis of Assisi. Olivier Messiaen: Saint François d'Assise

LEPIDO (i) Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, Roman triumvir Samuel Barber: Antony and Cleopatra

(ii) Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, heir to Emperor Caligula of Rome. Reinhard Keiser: Octavia

LUCAN. Lucan, Roman poet. Claudio Monteverdi: L'incoronazione di Poppea

LUCREZIA. Roman noblewoman raped by Sextus Tarquinius (legendary). Benjamin Britten: The Rape of Lucretia. Ottorino Respighi: Lucrezia

---- M -----

MACEDONIO. Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus, Roman general, natural father of Scipio Aemilianus. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Il sogno di Scipione, K. 126

MECENA. Gaius Maecenas, political adviser to Octavian (Caesar Augustus). Samuel Barber: Antony and Cleopatra

MALATESTA, Giovanni Malatesta, husband and murderer of Francesca da Rimini. Sergei Rachmaninoff: Francesca da Rimini (as Lanciotto Malatesta). Riccardo Zandonai: Francesca da Rimini (as Giovanni lo Sciancato)

MALATESTA, Malatestino, Lord of Rimini. Riccardo Zandonai: Francesca da Rimini (as Malatestino dall'Occhio)

MALATESTA, Paolo. Brother-in-law and lover of Francesca da Rimini. Sergei Rachmaninoff: Francesca da Rimini. Riccardo Zandonai: Francesca da Rimini (as Paolo il Bello)

MARCELLO, Benedetto. Italian composer. Joachim Raff: Benedetto Marcello

MARIA CELESTE. Sister Maria Celeste, Italian nun, illegitimate daughter of Galileo Galilei. Philip Glass: Galileo Galilei

MARIA LUISA. Duchess of Parma, wife of Napoleon I

MARC'ANTONIO -- vide ANTONIO. Mark Antony, Roman politician and general

Samuel Barber: Antony and Cleopatra. Domenico Cimarosa: La Cleopatra. Louis Gruenberg: Antony and Cleopatra. Henry Kimball Hadley: Cleopatra's Night. Giselher Klebe: Die Ermordung Cäsars

Jules Massenet: Cléopâtre

Masinissa, first King of Numidia

Francesco Cavalli: Scipione affricano

Mata Hari, Dutch spy

Gavin Bryars, Philip Glass and others: The Civil Wars: A Tree Is Best Measured When It Is Down

Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor

Antonín Dvořák: King and Charcoal Burner

King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary

Ferenc Erkel: Hunyadi László (as Mátyás Hunyadi)

Maurice, Elector of Saxony

Ernst Krenek: Karl V

Maurice de Saxe

Francesco Cilea: Adriana Lecouvreur

Jacques Offenbach: Madame Favart

Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maximianus Herculius, aka Maximian, Roman ruler

Gaetano Donizetti: Fausta

Maximinian, co-Emperor of Rome

Henry Purcell: Dioclesian

Ivan Mazepa, Cossack hetman, military leader

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Mazeppa

Cosimo de' Medici, ruler of Florence

Fromental Halévy: Guido et Ginevra

MEDICI. Giuliano di Piero de' Medici (nato a Firenze, 28 ottobre 1453 – Firenze, 26 aprile 1478) è stato un politico italiano. Brother of Lorenzo il Magnifico. La Congiura dei Pazzi, conclusa il 26 aprile 1478, fu il tentativo eseguito da alcuni membri dalla ricca famiglia di banchieri della Firenze del Rinascimento, i Pazzi appunto, di stroncare l'egemonia dei Medici con alcuni aiuti esterni. La congiura si concluse con l'uccisione di Giuliano de' Medici e il ferimento di Lorenzo il Magnifico, che si salvò solo grazie alla sua destrezza. I componenti della famiglia Medici, da sempre al centro della politica cittadina, hanno subito almeno una congiura per generazione. Cosimo de' Medici venne esiliato per motivi politici per un anno, mentre suo figlio Piero de' Medici scampò per miracolo a un'imboscata tesagli da Luca Pitti sulla via per Careggi, e così anche le generazioni successive, Leone X avrebbe dovuto essere ucciso dal suo medico, istruito da un gruppo di cardinali a lui avversi, e Cosimo I de' Medici rischiò di essere impallinato al passaggio del suo corteo davanti a Palazzo Pucci. La congiura dei Pazzi fu però l'unica congiura che riuscì nell'intento di eliminare un componente della famiglia e portò conseguenze durevoli, in giornate concitate che rimasero indelebili nella memoria dei fiorentini che vi parteciparono. Bertoldo di Giovanni, medaglia della congiura dei Pazzi, in basso

mostra Lorenzo che si salva dai congiurati, scena ambientata attorno al vecchio

coro di Santa Maria del Fiore, con in alto il profilo di Lorenzo. Dal 1469

Firenze era di fatto retta dai figli di Piero de' Medici, scomparso quell'anno, Lorenzo de' Medici,e

Giuliano de' Medici, che allora avevano rispettivamente venti e sedici anni. Lorenzo

de' Medici seguiva attivamente la vita politica con lo stesso metodo di suo nonno Cosimo de' Medici,

cioè senza ricevere incarichi diretti ma controllando tutte le magistrature e i

punti chiave attraverso uomini di fiducia. Non è chiaro se l'idea di una

congiura nacque a Firenze dalla famiglia Pazzi o piuttosto a Roma, nella mente

del loro più importante alleato, Francesco della Rovere (Papa Sisto IV). In ogni caso l'idea di eliminare

fisicamente i signori di fatto di Firenze catalizzò tutta una serie di figure a

loro avverse, che si organizzarono nella congiura vera e propria. Con

l'elezione al soglio pontificio di Sisto IV Della Rovere (1471), il nuovo papa,

sfrenato nepotista, aveva manifestato infatti l'interesse ad impadronirsi dei

ricchi territori fiorentini per i suoi nipoti, tra i quali il nobile Girolamo

Riario, e per le sue costose opere a Roma (come l'abbellimento e

riorganizzazione della Biblioteca Vaticana da lui promosso). Egli inoltre vedeva

con occhio sfavorevole le mire espansionistiche dei Medici verso la

Romagna.

Francesco della Rovere aveva anche già manifestato la sua opposizione ai Medici, esautorandoli dall'amministrazione delle finanze pontificie in favore della famiglia dei Pazzi, appunto. Essi sostenevano davanti a Lorenzo de' Medici che questo cambio di preferenza era dovuto solo ai loro meriti commerciali, non a scorrettezze, ma Il Magnifico probabilmente aspettò il momento giusto per vendicarsi di questo smacco commerciale. Tenere le finanze pontificie infatti portava enorme prestigio e ricchezza, sia dalle commissioni sui movimenti, sia dallo sfruttamento delle miniere di allume dei Monti della Tolfa, in territorio pontificio presso Civitavecchia, le uniche allora conosciute in Italia, garantendo il monopolio di questo insostituibile fissante per la tintura dei panni e per i colori delle miniature. Quindi i Pazzi e il papa erano in stretta alleanza a Roma, ma ancora l'idea di una congiura non doveva essersi manifestata, anzi le due famiglie fiorentine, sebbene rivali, erano anche imparentate dopo il matrimonio tra Guglielmo de' Pazzi e Bianca de' Medici, sorella di Lorenzo, nel 1469. La scintilla che accese gli animi viene di solito individuata nella questione dell'eredità di Beatrice Borromei, moglie di Giovanni de' Pazzi. Nel 1477, dopo la morte del suo ricchissimo padre Giovanni Borromei, Lorenzo fece promulgare una legge retroattiva che privava le figlie femmine dell'eredità in assenza di fratelli, facendola passare direttamente ad eventuali cugini maschi. Così Lorenzo evitò una notevole crescita del patrimonio dei Pazzi. La frattura tra le due famiglie si manifestò rapidamente, anche quando Lorenzo rinfacciò ai Pazzi di aver prestato trentamila ducati al papa affinché suo nipote si impossessasse della Contea di Imola, così pericolosamente a ridosso dei territori fiorentini, prestito che il Banco Medici aveva già rifiutato e che egli aveva chiesto di non fare a nessun banco fiorentino. Fu probabilmente in quel periodo (1477 circa) che la congiura prese piede, soprattutto ad opera di Jacopo e Francesco de' Pazzi. Ad essi si aggiunse Francesco Salviati, arcivescovo di Pisa, in attrito coi Medici che avevano tramato per non dargli la cattedra fiorentina favorendo invece un loro congiunto, (Rinaldo Orsini). La guida di Firenze liberata sarebbe dovuta spettare a Girolamo Riario. Il papa si premurò di trovare altri appoggi esterni: la Repubblica di Siena, il Re di Napoli, oltre alle truppe inviate dalle città di Todi, di Città di Castello, di Perugia e Imola (tutti territori pontifici). Il pontefice raccomandò di evitare spargimenti di sangue, ma questo suggerimento venne ignorato dai congiurati: i due Medici infatti dovevano essere eliminati fisicamente. Il braccio dell'azione, inteso come responsabile dell'omicidio o con stratagemmi o di suo pugno, era rappresentato da Giovan Battista Montesecco, sicario di professione. Recentemente è stata scoperta, dal professor Marcello Simonetta, una lettera cifrata che prova con certezza il fondamentale coinvolgimento di Federico da Montefeltro, Duca d'Urbino, nella congiura, e Lorenzo non sospettò mai di lui. Sabato 25 aprile 1478 . Originariamente, il piano prevedeva di uccidere i due rampolli della famiglia Medici, Lorenzo de' Medici e Giuliano de' Medici, durante un banchetto che essi avevano organizzato alla Villa Medici, Fiesole il 25 aprile, tramite l'uso di veleno che Jacopo de' Pazzi e il Riario avrebbero nascosto in una delle libagioni destinate ai due fratelli. L'occasione del banchetto era data dall'elezione a cardinale del diciottenne Raffaele Riario, forse ignaro delle trame dei congiurati -- in realtà forse avvisato dallo zio Sisto IV. I Pazzi si erano di recente imparentati con i Medici, tramite il matrimonio della sorella di Lorenzo e Giuliano, Bianca de' Medici con Guglielmo de' Pazzi. Quel giorno però un'indisposizione improvvisa di Giuliano rese vana l'impresa che fu rimandata al giorno successivo, durante la Messa in Santa Maria del Fiore. Domenica 26 aprile 1478.

La domenica l'ignaro cardinale Riario Sansoni invitò tutti alla messa in Duomo da lui officiata, come ringraziamento della festa organizzata il giorno prima in suo onore. Alla messa si recarono Lorenzo de' Medici, Giuliano de' Medici e i congiurati, i Pazzi, con l'eccezione però del Montesecco, che si rifiutò di colpire a tradimento dentro un luogo consacrato. Vennero allora ingaggiati in fretta e furia due preti in sostituzione: Stefano da Bagnone e il vicario apostolico Antonio Maffei da Volterra.

Essendo però Giuliano de' Medici ancora indisposto, Bernardo Bandini (il sicario destinato a Giuliano de' Medici) e Francesco de' Pazzi decisero di andare a prenderlo personalmente. Nel percorso dal Palazzo Medici a Santa Maria del Fiore, i cronisti ricordano come i congiurati abbracciassero a tradimento Giuliano de' Medici per vedere se indossasse una cotta di maglia sotto le vesti, ma egli a causa di un'infezione ad una gamba era uscito senza indossare il solito giaco sotto le vesti, che lo proteggeva, e senza il suo "gentile", nome scherzoso con il quale usava chiamare il suo coltello da guerra, che gli sbatteva contro la gamba ferita. Quando arrivarono in chiesa la messa era già iniziata. Al momento solenne dell'elevazione, mentre tutti erano inginocchiati, si scatenò il vero e proprio agguato. Mentre Giuliano cadeva in un lago di sangue sotto i colpi del Bandini, Lorenzo, accompagnato dall'inseparabile Angelo Poliziano e dai suoi scudieri Andrea e Lorenzo Cavalcanti, veniva ferito di striscio sulla spalla dagli inesperti preti e riusciva a entrare in sacrestia, dove chiuse le pesanti porte e si barricò. Il Bandini si avventò, ormai in ritardo, e sfogò la sua foga su Francesco Nori, che interpose il suo corpo tra l'omicida e Lorenzo, sacrificando la sua vita e dando la possibilità a Lorenzo di fuggire. Giuliano de' Medici venne sepolto in San Lorenzo, in quella che sarà la Sagrestia Nuova di Michelangelo. A un sopralluogo nella sua tomba condotto nel 2004 fu ritrovato il suo teschio con i segni di un profondo taglio nella testa. Un frammento di camicia insanguinata è stato a lungo ritenuto un brandello della camicia indossata da Giuliano de’ Medici al momento dell’uccisione in duomo. Come tale fu inserito in una teca ed esposto nel Museo Mediceo allestito in Palazzo Medici Riccardi: solo recentemente è stato dimostrato trattarsi di un brandello dell’abito del duca Alessandro, assassinato nel 1537. Attesta però, quasi reliquia laica, il perdurare del potere evocativo della Congiura che si era proposta di cambiare la storia fiorentina. Jacopo de' Pazzi aveva completamente sbagliato la valutazione della risposta della popolazione fiorentina. Quando si presentò in Piazza della Signoria con un gruppo di compagni a cavallo gridando "Libertà!" invece di essere acclamato venne assalito dalla folla in un incontenibile movimento popolare che dal Duomo a tutta la città si accaniva contro i congiurati. Le truppe del papa e delle altre città che attendevano appostate attorno a Firenze, al suono delle campane sciolte si insospettirono e lo stesso Jacopo de' Pazzi uscì dalla città portando la notizia del fallimento, per cui non fu sferrato nessun attacco. L'epilogo fu molto doloroso per i Pazzi e per i loro alleati tanto che entro poche ore dall'agguato Francesco, ferito nell'agguato e rifugiatosi nella sua casa, e l'arcivescovo di Pisa Francesco Salviati penzolavano impiccati dalle finestre del Palazzo della Signoria. Al grido di "Palle, palle!", ispirato al blasone dei Medici, i Palleschi scatenarono infatti una vera e propria caccia all'uomo in città, che fu feroce e fulminea. Pochi giorni dopo anche Jacopo de' Pazzi veniva impiccato, e anche il suo congiunto, non responsabile della congiura, Renato de' Pazzi, e i loro corpi gettati nell'Arno. Bernardo Bandini riuscì a fuggire dalla città, arrivando a rifugiarsi a Costantinopoli, ma venne scovato e consegnato a Firenze per essere giustiziato il 29 dicembre 1479. Il suo cadavere impiccato venne ritratto da Leonardo da Vinci. Giovan Battista da Montesecco, sebbene non avesse partecipato all'esecuzione della congiura, venne arrestato e, dopo essere stato sottoposto alla tortura, rivelò i particolari della macchinazione, compreso il coinvolgimento del papa, che egli additò come il principale responsabile. Fu decapitato. I due preti assassini vennero catturati pochi giorni dopo e linciati dalla folla: ormai tumefatti e senza orecchie, giunsero al patibolo in Piazza della Signoria e vennero impiccati. Lorenzo non fece niente per mitigare la furia popolare, così fu vendicato senza che le sue mani si macchiassero di colpe. I Pazzi vennero tutti arrestati o esiliati e i loro beni confiscati. Fu proibito che il loro nome comparisse su alcun documento ufficiale e vennero cancellati tutti gli stemmi di famiglia dalla città, compresi quelli che erano presenti su alcuni fiorini coniati dal loro banco, che furono riconiati. In un primo momento il papa scomunicò la città di Firenze, ma successivamente si trovò isolato quando Ferrante d'Aragona appoggiò Lorenzo, che si era recato personalmente a Napoli. Lorenzo colse così l'occasione per serrare il potere nelle sue mani: subordinò infatti le assemblee comunali e la struttura della Repubblica a un consiglio di 70 membri, in larga parte persone di sua fiducia, che doveva rispondere solo a lui. Uno dei più antichi e famosi resoconti della vicenda fu scritto in latino da Angelo Poliziano stesso, che aveva assistito direttamente ai fatti.

In seguito Lorenzo riuscì a pacificarsi sia con Alfonso che con papa Sisto: in entrambi i casi usò la cultura e l'arte come ambasciatori di Firenze e della sua necessaria libertà e indipendenza: partirono così per Napoli Giuliano, Benedetto da Maiano e Antonio Rossellino, mentre un gruppo di artisti fiorentini affrescò a Roma la nuova Cappella Sistina tra il 1481 e il 1482. Note: vedi catalogo della mostra "Denaro e Bellezza. I banchieri, Botticelli e il rogo delle vanità" Firenze, Palazzo Strozzi, 17 settembre 2011-22 gennaio 2012. Voci correlate [modifica] Medaglia della Congiura dei Pazzi

La congiura de' Pazzi (tragedia di Vittorio Alfieri) Assedio di Colle Val d'Elsa. Bibliografia: Medici, Associazioni alberghi del libro d'oro, Nike edizioni, 2001.Le grandi famiglia di Firenze, Marcello Vannucci, Newton Compton Editori, 2006. Vedi anche la bibliografia su Firenze. Collegamenti esterni [modifica] Una cronologia dei giorni della Congiura Uno studio sulla congiura (DOC) Un articolo sulle responsabilità di Federico da Montefeltro nella congiura. Portale Firenze Portale Storia.

Categorie: Storia di Firenze Rinascimento. The Pazzi conspiracy was a plot by members of the Pazzi family and others to displace the de' Medici family as rulers of Renaissance Florence. On 26 Apr. 1478 there was an attempt to assassinate Lorenzo de' Medici and his brother Giuliano de' Medici. Lorenzo was wounded but survived. Giuliano was killed. The partial failure of the plot served to strengthen the position of the de' Medici.

Francesco della Rovere aveva anche già manifestato la sua opposizione ai Medici, esautorandoli dall'amministrazione delle finanze pontificie in favore della famiglia dei Pazzi, appunto. Essi sostenevano davanti a Lorenzo de' Medici che questo cambio di preferenza era dovuto solo ai loro meriti commerciali, non a scorrettezze, ma Il Magnifico probabilmente aspettò il momento giusto per vendicarsi di questo smacco commerciale. Tenere le finanze pontificie infatti portava enorme prestigio e ricchezza, sia dalle commissioni sui movimenti, sia dallo sfruttamento delle miniere di allume dei Monti della Tolfa, in territorio pontificio presso Civitavecchia, le uniche allora conosciute in Italia, garantendo il monopolio di questo insostituibile fissante per la tintura dei panni e per i colori delle miniature. Quindi i Pazzi e il papa erano in stretta alleanza a Roma, ma ancora l'idea di una congiura non doveva essersi manifestata, anzi le due famiglie fiorentine, sebbene rivali, erano anche imparentate dopo il matrimonio tra Guglielmo de' Pazzi e Bianca de' Medici, sorella di Lorenzo, nel 1469. La scintilla che accese gli animi viene di solito individuata nella questione dell'eredità di Beatrice Borromei, moglie di Giovanni de' Pazzi. Nel 1477, dopo la morte del suo ricchissimo padre Giovanni Borromei, Lorenzo fece promulgare una legge retroattiva che privava le figlie femmine dell'eredità in assenza di fratelli, facendola passare direttamente ad eventuali cugini maschi. Così Lorenzo evitò una notevole crescita del patrimonio dei Pazzi. La frattura tra le due famiglie si manifestò rapidamente, anche quando Lorenzo rinfacciò ai Pazzi di aver prestato trentamila ducati al papa affinché suo nipote si impossessasse della Contea di Imola, così pericolosamente a ridosso dei territori fiorentini, prestito che il Banco Medici aveva già rifiutato e che egli aveva chiesto di non fare a nessun banco fiorentino. Fu probabilmente in quel periodo (1477 circa) che la congiura prese piede, soprattutto ad opera di Jacopo e Francesco de' Pazzi. Ad essi si aggiunse Francesco Salviati, arcivescovo di Pisa, in attrito coi Medici che avevano tramato per non dargli la cattedra fiorentina favorendo invece un loro congiunto, (Rinaldo Orsini). La guida di Firenze liberata sarebbe dovuta spettare a Girolamo Riario. Il papa si premurò di trovare altri appoggi esterni: la Repubblica di Siena, il Re di Napoli, oltre alle truppe inviate dalle città di Todi, di Città di Castello, di Perugia e Imola (tutti territori pontifici). Il pontefice raccomandò di evitare spargimenti di sangue, ma questo suggerimento venne ignorato dai congiurati: i due Medici infatti dovevano essere eliminati fisicamente. Il braccio dell'azione, inteso come responsabile dell'omicidio o con stratagemmi o di suo pugno, era rappresentato da Giovan Battista Montesecco, sicario di professione. Recentemente è stata scoperta, dal professor Marcello Simonetta, una lettera cifrata che prova con certezza il fondamentale coinvolgimento di Federico da Montefeltro, Duca d'Urbino, nella congiura, e Lorenzo non sospettò mai di lui. Sabato 25 aprile 1478 . Originariamente, il piano prevedeva di uccidere i due rampolli della famiglia Medici, Lorenzo de' Medici e Giuliano de' Medici, durante un banchetto che essi avevano organizzato alla Villa Medici, Fiesole il 25 aprile, tramite l'uso di veleno che Jacopo de' Pazzi e il Riario avrebbero nascosto in una delle libagioni destinate ai due fratelli. L'occasione del banchetto era data dall'elezione a cardinale del diciottenne Raffaele Riario, forse ignaro delle trame dei congiurati -- in realtà forse avvisato dallo zio Sisto IV. I Pazzi si erano di recente imparentati con i Medici, tramite il matrimonio della sorella di Lorenzo e Giuliano, Bianca de' Medici con Guglielmo de' Pazzi. Quel giorno però un'indisposizione improvvisa di Giuliano rese vana l'impresa che fu rimandata al giorno successivo, durante la Messa in Santa Maria del Fiore. Domenica 26 aprile 1478.

La domenica l'ignaro cardinale Riario Sansoni invitò tutti alla messa in Duomo da lui officiata, come ringraziamento della festa organizzata il giorno prima in suo onore. Alla messa si recarono Lorenzo de' Medici, Giuliano de' Medici e i congiurati, i Pazzi, con l'eccezione però del Montesecco, che si rifiutò di colpire a tradimento dentro un luogo consacrato. Vennero allora ingaggiati in fretta e furia due preti in sostituzione: Stefano da Bagnone e il vicario apostolico Antonio Maffei da Volterra.

Essendo però Giuliano de' Medici ancora indisposto, Bernardo Bandini (il sicario destinato a Giuliano de' Medici) e Francesco de' Pazzi decisero di andare a prenderlo personalmente. Nel percorso dal Palazzo Medici a Santa Maria del Fiore, i cronisti ricordano come i congiurati abbracciassero a tradimento Giuliano de' Medici per vedere se indossasse una cotta di maglia sotto le vesti, ma egli a causa di un'infezione ad una gamba era uscito senza indossare il solito giaco sotto le vesti, che lo proteggeva, e senza il suo "gentile", nome scherzoso con il quale usava chiamare il suo coltello da guerra, che gli sbatteva contro la gamba ferita. Quando arrivarono in chiesa la messa era già iniziata. Al momento solenne dell'elevazione, mentre tutti erano inginocchiati, si scatenò il vero e proprio agguato. Mentre Giuliano cadeva in un lago di sangue sotto i colpi del Bandini, Lorenzo, accompagnato dall'inseparabile Angelo Poliziano e dai suoi scudieri Andrea e Lorenzo Cavalcanti, veniva ferito di striscio sulla spalla dagli inesperti preti e riusciva a entrare in sacrestia, dove chiuse le pesanti porte e si barricò. Il Bandini si avventò, ormai in ritardo, e sfogò la sua foga su Francesco Nori, che interpose il suo corpo tra l'omicida e Lorenzo, sacrificando la sua vita e dando la possibilità a Lorenzo di fuggire. Giuliano de' Medici venne sepolto in San Lorenzo, in quella che sarà la Sagrestia Nuova di Michelangelo. A un sopralluogo nella sua tomba condotto nel 2004 fu ritrovato il suo teschio con i segni di un profondo taglio nella testa. Un frammento di camicia insanguinata è stato a lungo ritenuto un brandello della camicia indossata da Giuliano de’ Medici al momento dell’uccisione in duomo. Come tale fu inserito in una teca ed esposto nel Museo Mediceo allestito in Palazzo Medici Riccardi: solo recentemente è stato dimostrato trattarsi di un brandello dell’abito del duca Alessandro, assassinato nel 1537. Attesta però, quasi reliquia laica, il perdurare del potere evocativo della Congiura che si era proposta di cambiare la storia fiorentina. Jacopo de' Pazzi aveva completamente sbagliato la valutazione della risposta della popolazione fiorentina. Quando si presentò in Piazza della Signoria con un gruppo di compagni a cavallo gridando "Libertà!" invece di essere acclamato venne assalito dalla folla in un incontenibile movimento popolare che dal Duomo a tutta la città si accaniva contro i congiurati. Le truppe del papa e delle altre città che attendevano appostate attorno a Firenze, al suono delle campane sciolte si insospettirono e lo stesso Jacopo de' Pazzi uscì dalla città portando la notizia del fallimento, per cui non fu sferrato nessun attacco. L'epilogo fu molto doloroso per i Pazzi e per i loro alleati tanto che entro poche ore dall'agguato Francesco, ferito nell'agguato e rifugiatosi nella sua casa, e l'arcivescovo di Pisa Francesco Salviati penzolavano impiccati dalle finestre del Palazzo della Signoria. Al grido di "Palle, palle!", ispirato al blasone dei Medici, i Palleschi scatenarono infatti una vera e propria caccia all'uomo in città, che fu feroce e fulminea. Pochi giorni dopo anche Jacopo de' Pazzi veniva impiccato, e anche il suo congiunto, non responsabile della congiura, Renato de' Pazzi, e i loro corpi gettati nell'Arno. Bernardo Bandini riuscì a fuggire dalla città, arrivando a rifugiarsi a Costantinopoli, ma venne scovato e consegnato a Firenze per essere giustiziato il 29 dicembre 1479. Il suo cadavere impiccato venne ritratto da Leonardo da Vinci. Giovan Battista da Montesecco, sebbene non avesse partecipato all'esecuzione della congiura, venne arrestato e, dopo essere stato sottoposto alla tortura, rivelò i particolari della macchinazione, compreso il coinvolgimento del papa, che egli additò come il principale responsabile. Fu decapitato. I due preti assassini vennero catturati pochi giorni dopo e linciati dalla folla: ormai tumefatti e senza orecchie, giunsero al patibolo in Piazza della Signoria e vennero impiccati. Lorenzo non fece niente per mitigare la furia popolare, così fu vendicato senza che le sue mani si macchiassero di colpe. I Pazzi vennero tutti arrestati o esiliati e i loro beni confiscati. Fu proibito che il loro nome comparisse su alcun documento ufficiale e vennero cancellati tutti gli stemmi di famiglia dalla città, compresi quelli che erano presenti su alcuni fiorini coniati dal loro banco, che furono riconiati. In un primo momento il papa scomunicò la città di Firenze, ma successivamente si trovò isolato quando Ferrante d'Aragona appoggiò Lorenzo, che si era recato personalmente a Napoli. Lorenzo colse così l'occasione per serrare il potere nelle sue mani: subordinò infatti le assemblee comunali e la struttura della Repubblica a un consiglio di 70 membri, in larga parte persone di sua fiducia, che doveva rispondere solo a lui. Uno dei più antichi e famosi resoconti della vicenda fu scritto in latino da Angelo Poliziano stesso, che aveva assistito direttamente ai fatti.

In seguito Lorenzo riuscì a pacificarsi sia con Alfonso che con papa Sisto: in entrambi i casi usò la cultura e l'arte come ambasciatori di Firenze e della sua necessaria libertà e indipendenza: partirono così per Napoli Giuliano, Benedetto da Maiano e Antonio Rossellino, mentre un gruppo di artisti fiorentini affrescò a Roma la nuova Cappella Sistina tra il 1481 e il 1482. Note: vedi catalogo della mostra "Denaro e Bellezza. I banchieri, Botticelli e il rogo delle vanità" Firenze, Palazzo Strozzi, 17 settembre 2011-22 gennaio 2012. Voci correlate [modifica] Medaglia della Congiura dei Pazzi

La congiura de' Pazzi (tragedia di Vittorio Alfieri) Assedio di Colle Val d'Elsa. Bibliografia: Medici, Associazioni alberghi del libro d'oro, Nike edizioni, 2001.Le grandi famiglia di Firenze, Marcello Vannucci, Newton Compton Editori, 2006. Vedi anche la bibliografia su Firenze. Collegamenti esterni [modifica] Una cronologia dei giorni della Congiura Uno studio sulla congiura (DOC) Un articolo sulle responsabilità di Federico da Montefeltro nella congiura. Portale Firenze Portale Storia.

Categorie: Storia di Firenze Rinascimento. The Pazzi conspiracy was a plot by members of the Pazzi family and others to displace the de' Medici family as rulers of Renaissance Florence. On 26 Apr. 1478 there was an attempt to assassinate Lorenzo de' Medici and his brother Giuliano de' Medici. Lorenzo was wounded but survived. Giuliano was killed. The partial failure of the plot served to strengthen the position of the de' Medici.

The Pazzi were banished from Florence. Ruggero Leoncavallo, "I Medici" (1893), with a libretto by the

composer. "I Medici" premièred at the Teatro Dal Verme in Milan on 9 November 1893.

It was not successful in its day and has never become part of the standard

repertoire. Conductor: Rodolfo Ferrari. Come riusci' Lorenzo de' Medici a sfuggire ai pugnali dei cospiratori? E perchè il complotto dei Pazzi falli' cosi' miseramente?