Vanbrugh and Congreve received Queen Anne's authority to form a Company of Comedians on 14 December 1704, and the theatre opened as The Queen's Theatre on 9 April 1705 with imported Italian singers in "Gli amori d'Ergasto", an opera by Giacomo Greber, with an epilogue by Congreve.

"Gli amori d'Ergasto", by Greber, was the first Italian opera performed in London.

The opera failed, and the season struggled on through May, with revivals of plays and operas.

The first new play performed was The Conquest of Spain by Mary Pix.

The theatre proved too large for actors' voices to carry across the auditorium, and the first season was a failure. Congreve departed, Vanbrugh bought out his other partners, and the actors reopened the Lincoln's Inn Fields' theatre in the summer.

Although early productions combined spoken dialogue with incidental music, a taste was growing amongst the nobility for Italian opera, which was completely sung, and the theatre became devoted to opera. As he became progressively more involved in the construction of Blenheim Palace, Vanbrugh's management of the theatre became increasingly chaotic, showing "numerous signs of confusion, inefficiency, missed opportunities, and bad judgement".

On 7 May 1707, experiencing mounting losses and running costs, Vanbrugh was forced to sell a lease on the theatre for fourteen years to Owen Swiny at a considerable loss. In December of that year, the Lord Chamberlain's Office ordered that "all Operas and other Musicall presentments be performed for the future only at Her Majesty's Theatre in the Hay Market" and forbade the performance of further non-musical plays there.

After 1709, the theatre was devoted to Italian opera and was sometimes known informally as The Haymarket Opera House.

Young George Frederick Handel was produced his English début, Rinaldo (tratto dalla "Gerusalemme liberata" di Tasso, su libretto di G. Rossi) on 24 February 1711 at the theatre, featuring the two leading castrati of the era, Nicolo Grimaldi and Valentino Urbani.

This was the first Italian opera composed specifically for the London stage.

The work was well received, and Handel was appointed resident composer for the theatre, but losses continued, and Swiney fled abroad to escape his creditors.

John James Heidegger took over the management of the theatre and, from 1719, began to extend the stage through arches into the houses to the south of the theatre.

A "Royal Academy of Music" was formed by subscription from wealthy sponsors, including the Prince of Wales, to support Handel's productions at the theatre.

Under this sponsorship, Handel conducted a series of more than 25 of his original operas, continuing until 1739[15] Handel was also a partner in the management with Heidegger from 1729 to 1734, and he contributed to incidental music for theatre, including for a revival of Ben Jonson's The Alchemist, opening on 14 January 1710.

On the accession of George I in 1714, the theatre was renamed the King's Theatre and remained so named during a succession of male monarchs who occupied the throne. At this time only the two patent theatres were permitted to perform serious drama in London, and lacking Letters patent, the theatre remained associated with opera.[17] In 1762, Johann Christian Bach travelled to London to première three operas at the theatre, including Orione on 19 February 1763. This established his reputation in England, and he became music master to Queen Charlotte.[18]

In 1778, the lease for the theatre was transferred from James Brook to Thomas Harris, stage manager of the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, and to the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan for £22,000. They paid for the remodelling of the interior by Robert Adam in the same year. In November 1778, The Morning Chronicle reported that Harris and Sheridan had

... at a considerable expence, almost entirely new built the audience part of the house, and made a great variety of alterations, part of which are calculated for the rendering the theatre more light, elegant, and pleasant, and part for the ease and convenience of the company. The sides of the frontispiece are decorated with two figures painted by Gainsborough, which are remarkably picturesque and beautiful; the heavy columns which gave the house so gloomy an aspect that it rather resembled a large mausoleum or a place for funeral dirges, than a theatre, are removed.The expense of the improvements was not matched by the box office receipts, and the partnership dissolved, with Sheridan buying out his partner with a mortgage on the theatre of £12,000 obtained from the banker Henry Hoare.[5]

—November 1778, The Morning Chronicle[5]

One member of the company, Giovanni Gallini, had made his début at the theatre in 1753 and had risen to the position of dancing master, gaining an international reputation. Gallini had tried to buy Harris' share but had been rebuffed. He now purchased the mortgage. Sheridan quickly became bankrupt after placing the financial affairs of the theatre in the hands of William Taylor, a lawyer. The next few years saw a struggle for control of the theatre, and Taylor bought Sheridan's interest in 1781. In 1782 the theatre was remodelled by Michael Novosielski, formerly a scene painter at the theatre. In May 1783, Taylor was arrested by his creditors, and a forced sale ensued, with Harris purchasing the lease and much of the effects. Further legal action transferred the interests in the theatre to a board of trustees, including Novosielski. The trustees acted with a flagrant disregard for the needs of the theatre or other creditors, seeking only to enrich themselves, and in August 1785 the Lord Chamberlain took over the running of the enterprise, in the interests of the creditors. Gallini, meanwhile, had become manager. In 1788, the Lord Chancellor observed "that there appeared in all the proceedings respecting this business, a wish of distressing the property, and that it would probably be consumed in that very court to which ... [the interested parties] seemed to apply for relief".[5] Performances suffered, with the box receipts taken by Novosielski, rather than given to Gallini to run the house. Money continued to be squandered on endless litigation or was misappropriated.[5] Gallini tried to keep the theatre going, but he was forced to employ amateur performers. The World described a performance as follows: "... the dance, if such it can be called was like the movements of heavy cavalry. It was hissed very abundantly."[19] At other times, Gallini had to defend himself against a dissatisfied audience who charged the stage and destroyed the fittings, as the company ran for their lives.[19]

The theatre burnt down on 17 June 1789 during evening rehearsals, and the dancers fled the building as beams fell onto the stage. The fire had been deliberately set on the roof, and Gallini offered a reward of £300 for capture of the culprit.[5] With the theatre destroyed, each group laid their own plans for a replacement. Gallini obtained a licence from the Lord Chamberlain to perform opera at the nearby Little Theatre, and he entered into a partnership with R. B. O'Reilly to obtain land in Leicester Fields for a new building, which too would require a licence. The two quarrelled, and each then planned to wrest control of the venture from the other. The authorities refused to grant either of them a patent for Leicester Fields, but O'Reilly was granted a licence for four years to put on opera at the Oxford Street Pantheon. This too, would burn to the ground in 1792. Meanwhile, Taylor reached an agreement with the creditors of the King's Theatre and attempted to purchase the remainder of the lease from Edward Vanbrugh, but this was now promised to O'Reilly. A further complication arose as the theatre needed to expand onto adjacent land that now came into the possession of a Taylor supporter. The scene was set for a further war of attrition between the lessees, but at this point O'Reilly's first season at the Pantheon failed miserably, and he fled to Paris to avoid his creditors.[5]

By 1720, Vanbrugh's direct connection with the theatre had been terminated, but the leases and rents had been transferred to both his own family and that of his wife's through a series of trusts and benefices, with Vanbrugh himself building a new home in Greenwich. After the fire, the Vanbrugh family's long association with the theatre was terminated, and all their leases were surrendered by 1792.[5]

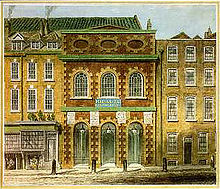

Taylor completed a new theatre on the site in 1791. Michael Novosielski had again been chosen as architect for the theatre on an enlarged site, but the building was described by Malcolm in 1807 as

...fronted by a stone basement in rustic work, with the commencement of a very superb building of the Doric order, consisting of three pillars, two windows, an entablature, pediment, and balustrade. This, if it had been continued, would have contributed considerably to the splendour of London; but the unlucky fragment is fated to stand as a foil to the vile and absurd edifice of brick pieced to it, which I have not patience to describe.The Lord Chamberlain, a supporter of O'Reilly, refused a performing licence to Taylor. The theatre opened on 26 March 1791 with a private performance of song and dance entertainment, but was not allowed to open to the public. The new theatre was heavily indebted and spanned separate plots of land that were leased to Taylor by four different owners on differing terms of revision. As a later manager of the theatre wrote, "In the history of property, there has probably been no parallel instance wherein the legal labyrinth has been so difficult to thread."[5] Meetings were held at Carlton House and Bedford House attempting to reconcile the parties. On 24 August 1792 a General Opera Trust Deed was signed by the parties. The general management of the theatre was to be entrusted to a committee of noblemen, appointed by the Prince of Wales, who would then appoint a general manager. Funds would be disbursed from the profits to compensate the creditors of both the King's Theatre and the Pantheon. The committee never met, and management devolved to Taylor.[

—The critic Malcolm, quoted in Old and New London (1878)[20]

No comments:

Post a Comment