History

Roman chronology

Founding myth

Main article: Founding of Rome

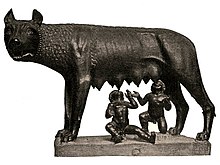

According to legend, Rome was founded in 753 BC by Romulus and Remus, who were raised by a she-wolf.

The new king feared Romulus and Remus would take back the throne, so he ordered them to be drowned.[10] A she-wolf (or a shepherd's wife in some accounts) saved and raised them, and when they were old enough, they returned the throne of Alba Longa to Numitor.[11][12]

The twins then founded their own city, but Romulus killed Remus in a quarrel over the location of the Roman Kingdom, though some sources state the quarrel was about who was going to rule or give his name to the city.[13] Romulus became the source of the city's name.[14] In order to attract people to the city, Rome became a sanctuary for the indigent, exiled, and unwanted. This caused a problem for Rome, which had a large workforce but was bereft of women. Romulus traveled to the neighboring towns and tribes and attempted to secure marriage rights but as Rome was so full of undesirables they all refused. Legend says that the Latins invited the Sabines to a festival and stole their unmarried maidens, leading to the integration of the Latins and the Sabines.[15]

Another legend, recorded by Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus, says that Prince Aeneas led a group of Trojans on a sea voyage to found a new Troy, since the original was destroyed in the outcome of the Trojan War. After a long time in rough seas, they landed at the banks of the Tiber River. Not long after they landed, the men wanted to take to the sea again, but the women who were traveling with them did not want to leave. One woman, named Roma, suggested that the women burn the ships out at sea to prevent them from leaving. At first, the men were angry with Roma, but they soon realized that they were in the ideal place to settle. They named the settlement after the woman who torched their ships.[16]

The Roman poet Vergil recounted this legend on his classical epic poem Aeneid. In the Aeneid, the Trojan prince Aeneas is destined by the gods in his enterprise of founding a new Troy. In the epic, the women also refused to go back to the sea, but they were not left on the Tiber. After reaching Italy, Aeneas, who wanted to marry Lavinia, was forced to wage war with her former suitor, Turnus. According to the poem, the Alban kings were descended from Aeneas, and thus, Romulus, the founder of Rome, was his descendant.

Kingdom

Main article: Roman Kingdom

The city of Rome grew from settlements around a ford on the river Tiber, a crossroads of traffic and trade.[17] According to archaeological evidence, the village of Rome was probably founded sometime in the 8th century BC, though it may go back as far as the 10th century BC, by members of the Latin tribe of Italy, on the top of the Palatine Hill.[18][19]The Etruscans, who had previously settled to the north in Etruria, seem to have established political control in the region by the late 7th century BC, forming the aristocratic and monarchical elite. The Etruscans apparently lost power in the area by the late 6th century BC, and at this point, the original Latin and Sabine tribes reinvented their government by creating a republic, with much greater restraints on the ability of rulers to exercise power.[20]

Roman tradition and archaeological evidence point to a complex within the Forum Romanum as the seat of power for the king and the beginnings of the religious center there as well. Numa Pompilius was the second king of Rome, succeeding Romulus. He began Rome's great building projects with his royal palace the Regia and the complex of the Vestal virgins.

Republic

Main article: Roman Republic

This bust from the Capitoline Museums is traditionally identified as a portrait of Lucius Junius Brutus.

Other magistracies in the Republic include tribunes, quaestors, aediles, praetors and censors.[25] The magistracies were originally restricted to patricians, but were later opened to common people, or plebeians.[26] Republican voting assemblies included the comitia centuriata (centuriate assembly), which voted on matters of war and peace and elected men to the most important offices, and the comitia tributa (tribal assembly), which elected less important offices.[27]

Italy in 400 BC.

The Romans gradually subdued the other peoples on the Italian peninsula, including the Etruscans.[29] The last threat to Roman hegemony in Italy came when Tarentum, a major Greek colony, enlisted the aid of Pyrrhus of Epirus in 281 BC, but this effort failed as well.[30][31] The Romans secured their conquests by founding Roman colonies in strategic areas, thereby establishing stable control over the region of Italy.[32]

Punic Wars

Main article: Punic Wars

In the 3rd century BC Rome had to face a new and formidable opponent: Carthage. Carthage was a rich, flourishing Phoenician city-state that intended to dominate the Mediterranean area. The two cities were allies in the times of Pyrrhus, who was a menace to both, but with Rome's hegemony in mainland Italy and the Carthaginian thalassocracy, these cities became the two major powers in the Western Mediterranean – a signal of the imminent war.The First Punic War war begun in 264 BC, when the city of Messana asked for Carthage's help in dealing with Hiero II of Syracuse. After the Carthaginian intercession, Messana asked Rome to expel the Carthaginians. Rome entered this war because Syracuse and Messana were too close of the newly conquered Greek cities of Southern Italy and Carthage was now able to make an offensive through Roman territory; along with this, Rome could extend its domain over Sicily.[33]

Although the Romans had experience in land battles, to defeat this new enemy, naval battles were necessary. Carthage was a maritime power, and the Roman lack of ships and naval experience would make the path to the victory harsh for the Roman Republic. Despite this, after more than 20 years of war, Rome finally defeated Carthage and a peace treaty was signed. Among the reasons for the Second Punic War[34] was the subsequent war reparations Carthage acquiesced to at the end of the First Punic War.[35]

The Second Punic War is famous for its brilliant generals: on the Punic side Hannibal and Hasdrubal, and the Romans Marcellus, Fabius Maximus and Scipio Africanus. Rome faced this war simultaneously with the First Macedonian War.

The outbreak of the war was the audacious invasion of Italy led by Hannibal, son of Hamilcar Barca the Carthaginian general who was in charge of Sicily the First Punic War. Hannibal rapidly marched through Hispania and the Alps. This invasion caused panic in the cities and the only way to deflect Hannibal's intentions was to delay him in small battles. This strategy was led by Fabius Maximus, who would be nicknamed Cunctator ("delayer" in Latin), and until this day is called Fabian strategy. Due to this, Hannibal's goal was unachieved: he couldn't bring Italian cities to revolt against Rome and as his army diminished after every battle, he lacked machines and manpower to besiege Rome.

Hannibal's invasion lasted over 16 years, by ravaging the supplies of the Italian cities and fields. When the Romans perceived that his supplies were running out, they invaded the unprotected Carthage and forced Hannibal to go back to that city. On his return he faced Scipio, who had defeated his brother Hasdrubal. The result of this confrontation was the end of the Second Punic War in the famous Battle of Zama in October 202 BC, which gave to Scipio his agnomen Africanus. Rome's final debt was of many deaths, but also of resounding gains: the conquest of Hispania by Scipio and of Syracuse, the last Greek realm in Sicily, by Marcellus.

More than a half century after these events, Carthage was humiliated and Rome was no more concerned about the African menace. The Republic's focus now was only to the Hellenistic kingdoms of Greece and revolts in Hispania. However, Carthage after having paid the war indemnity, felt that its commitments and submission to Rome had ceased – a vision not shared by the Roman Senate. In 151 BC Numidia invaded Carthage, and after asking for Roman help, ambassadors were sent to Carthage, among them was Marcus Porcius Cato, who after seeing that Carthage could make a comeback and regain its importance, ended all his speeches, no matter what the subject was, by saying: "Ceterum censeo Carthaginem esse delendam" ("Furthermore, I think that Carthage must be destroyed").

As Carthage fought with Numidia without Roman consent, Rome declared war against Carthage in 149 BC. Carthage resisted well at the first strike, with the participation of all the inhabitants of the city. However, Carthage could not withstand the attack of Scipio Aemilianus, who entirely destroyed the city and its walls, enslaved and sold all the citizens and gained control of that region, which became the province of Africa and thus, ending the Punic War period.

All these wars resulted in Rome's first overseas conquests, of Sicily, Hispania and Africa and the rise of Rome as a significant imperial power.[36][37]

Late Republic

After defeating the Macedonian and Seleucid Empires in the 2nd century BC, the Romans became the dominant people of the Mediterranean Sea.[38][39] The conquest of the Hellenistic kingdoms provoked a fusion between Roman and Greek cultures and the Roman elite, once rural, became a luxurious and cosmopolitan one. By this time Rome was a consolidated empire – in the military view – and had no major enemies.Foreign dominance led to internal strife. Senators became rich at the provinces' expense, but soldiers, who were mostly small-scale farmers, were away from home longer and could not maintain their land, and the increased reliance on foreign slaves and the growth of latifundia reduced the availability of paid work.[40][41]

Income from war booty, mercantilism in the new provinces, and tax farming created new economic opportunities for the wealthy, forming a new class of merchants, the equestrians.[42] The lex Claudia forbade members of the Senate from engaging in commerce, so while the equestrians could theoretically join the Senate, they were severely restricted in political power.[17][43] The Senate squabbled perpetually, repeatedly blocking important land reforms and refusing to give the equestrian class a larger say in the government.

Violent gangs of the urban unemployed, controlled by rival Senators, intimidated the electorate through violence. The situation came to a head in the late 2nd century BC under the Gracchi brothers, a pair of tribunes who attempted to pass land reform legislation that would redistribute the major patrician landholdings among the plebeians. Both brothers were killed and the Senate passed reforms reversing the Gracchi brother's actions.[44] This led to the growing divide of the plebeian groups (populares) and equestrian classes (optimates).

Marius and Sulla

Gaius Marius, a novus homo, started his political career with the help of the powerful Metelli and soon become a leader of the Republic, holding the first of his seven consulships (a unprecedented experience) in 107 BC by arguing that his former patron Quintus Caecilius Metellus Numidicus was not able to defeat and capture the Numidian king Jugurtha. Marius then started his military reform: in his recruitment to fight Jugurtha, he levied very poor men (an innovation), and many landless men entered the army – this was the seed of securing loyalty of the army to the General in command.At this time, Marius began his quarrel with Lucius Cornelius Sulla: Marius, who wanted to capture Jugurtha, asked Bocchus, son-in-law of Jugurtha, to hand him over to the Romans. As Marius failed, Sulla – a legate of Marius at that time – went himself to Bocchus in a dangerous enterprise and convinced Bocchus to hand Jugurtha over to him. This was very provocative to Marius, since many of his enemies were encouraging Sulla to oppose Marius. Despite this, Marius was elected for five consecutive consulships from 104–100 BC, because Rome needed a military leader to defeat the Cimbri and the Teutones, who were threatening Rome.

After Marius's retirement, Rome had a brief peace, in which the Italian socii ("allies" in Latin) requested Roman citizenship and voting rights. The reformist Marcus Livius Drusus supported their legal process, but he was assassinated and the socii revolted against the Romans in the Social War. At one point both consuls were killed; Marius was appointed to command the army together with Lucius Julius Caesar and Sulla.[45]

By the ending of the Social War, Marius and Sulla were the premier military men in Rome and their partisans were in conflict, both sides jostling for power. In 88 BC, Sulla was elected for his first consulship and his first assignment was to defeat Mithridates of Pontus, whose intentions were to conquer the Eastern part of the Roman territories. However, Marius's partisans managed his installation to the military command, defying Sulla and the Senate, and this caused Sulla's wrath. To consolidate his own power, Sulla conducted a surprising and illegal action: he marched to Rome with his legions, killing all those who showed support to Marius's cause and impaling their heads in the Roman Forum. In the following year, 87 BC, Marius, who had fled at Sulla's march, came back to Rome while Sulla was campaigning in Greece. He seized power along with the consul Lucius Cornelius Cinna and killed the other consul, Gnaeus Octavius, achieving to his seventh consulship. In an attempt to raise Sulla's anger, Marius and Cinna revenged their partisans conducting a massacre[45] (Marian Massacre) and having impaled the heads of Sulla's supporters (as earlier Publius Sulpicius Rufus was impaled similarly by Sulla on the rostra).[46]

Marius died in 86 BC, due to his age and poor health, just a few months after seizing power. Cinna exercised absolute power until his death in 84 BC. Sulla after returning from his Eastern campaigns, had a free path to reestablish his own power. In 83 BC he made his second march in Rome and started a more sanguinary time of terror: thousands of nobles, knights and senators were executed. Sulla also held two dictatorships and one more consulship, which established the crisis and decline of Roman Republic.[45]

Caesar and the First Triumvirate

Bust of Caesar from the Naples National Archaeological Museum.

Onto this turbulent scene emerged Gaius Julius Caesar, from a very aristocratic family of limited wealth. His aunt Julia was Marius' wife,[47] and Caesar identified with the populares. To achieve power, Caesar reconciled the two most powerful men in Rome: Marcus Licinius Crassus, who had financed much of his earlier career, and Crassus' rival, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (anglicized as Pompey), to whom he married his daughter. He formed them into a new informal alliance including himself, the First Triumvirate ("three men"). This satisfied the interests of all three: Crassus, the richest man in Rome, became richer and ultimately achieved high military command; Pompey exerted more influence in the Senate; and Caesar obtained the consulship and military command in Gaul.[48] So long as they agreed, the three were in effect the rulers of Rome.

In 54 BC, Caesar's daughter, Pompey's wife, died in childbirth, unraveling one link in the alliance. In 53 BC, Crassus invaded Parthia and was killed in the Battle of Carrhae. The Triumvirate disintegrated at Crassus' death. Crassus had acted as mediator between Caesar and Pompey, and, without him, the two generals manoeuvred against each other for power. Caesar conquered Gaul, obtaining immense wealth, respect in Rome and the loyalty of battle-hardened legions. He also became a clear menace to Pompey and was loathed by many optimates. Confident that Caesar could be stopped by legal means, Pompey's party tried to strip Caesar of his legions, a prelude to Caesar's trial, impoverishment, and exile.

To avoid this fate, Caesar crossed the Rubicon River and invaded Rome in 49 BC. Pompey and his party fled from Italy, pursued by Caesar. The Battle of Pharsalus was a brilliant victory for Caesar and in this and other campaigns he destroyed all of the optimates' leaders: Metellus Scipio, Cato the Younger, and Pompey's son, Gnaeus Pompeius. Pompey was murdered in Egypt in 48 BC. Caesar was now pre-eminent over Rome, attracting the bitter enmity of many aristocrats. He was granted many offices and honours. In just five years, he held four consulships, two ordinary dictatorships, and two special dictatorships: one for ten years and another for perpetuity. He was murdered in 44 BC, in the Ides of March by the Liberatores.[49]

Octavian and the Second Triumvirate

The Battle of Actium, by Lorenzo Castro, painted 1672, National Maritime Museum, London

In 42 BC, the Senate deified Caesar as Divus Iulius, (note that Divus means "deified", and not "god". The Latin word for god is Deus; this word is used for real deities as Jupiter and Apollo. However, a Divus is not a deity, but a remarkable person who was as important to Rome as Romulus was.) Octavian thus became Divi filius,[52] the son of the deified. In the same year, Octavian and Antony defeated both Caesar's assassins and the leaders of the Liberatores, Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus, in the Battle of Philippi.

The Second Triumvirate was marked by the proscriptions of many senators and equites: after a revolt led by Antony's brother Lucius Antonius more than 300 senators and equites involved were executed on the anniversary of the Ides of March, although Lucius was spared.[53] The Triumvirate proscribed several important men, including Cicero, whom Antony hated;[54] Quintus Tullius Cicero, the younger brother of the orator; and, more shockingly, Lucius Julius Caesar, cousin and friend of the acclaimed general, for his support of Cicero. However, Lucius was pardoned, perhaps because his sister Julia had intervened for him.[55]

The Triumvirate divided the Empire among the triumvirs: Lepidus was left in charge of Africa, Antony, the eastern provinces, and Octavian remained in Italy and controlled Hispania and Gaul.

The Second Triumvirate expired in 38 BC but was renewed for five more years. However, the relationship between Octavian and Antony had deteriorated, and Lepidus was forced to retire in 36 BC after betraying Octavian in Sicily. By the end of the Triumvirate, Antony was living in Egypt, an independent and rich kingdom ruled by Antony's lover, Cleopatra VII. Antony's affair with Cleopatra was seen as an act of treason, since she was queen of another country and Antony was adopting an extravagant and Hellenistic lifestyle that was considered inappropriate for a Roman statesman.[56]

Following Antony's Donations of Alexandria, which gave to Cleopatra the title of "Queen of Kings", and to Antony's and Cleopatra's children the regal titles to the newly conquered Eastern territories, the war between Octavian and Antony broke out. Octavian annihilated Egyptian forces in the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide. Now Egypt was conquered by the Roman Empire, and for the Romans, a new era had begun.

Empire

Main article: Roman Empire

In 27 BC, Octavian was the sole Roman leader. His leadership brought the zenith of the Roman civilization, that lasted for two centuries. In that year, he took the name Augustus. That event is usually taken by historians as the beginning of Roman Empire – although Rome was an "imperial" state since 146 BC, when Carthage was razed by Scipio Aemilianus and Greece was conquered by Lucius Mummius. Officially, the government was republican, but Augustus assumed absolute powers.[57][58] Besides that, the Empire was safer, happier and more glorious than the Roman Republic.[58]Julio-Claudian dynasty

The Julio-Claudian dynasty was established by Augustus. The emperors of this dynasty were: Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and Nero. The dynasty is so-called due to the gens Julia, family of Augustus, and the gens Claudia, family of Tiberius. The Julio-Claudians started the destruction of republican values, but on the other hand, they boosted Rome's status as the central power in the world.[59]While Caligula and Nero are usually remembered as mad or mean emperors in popular culture, Augustus and Claudius were great emperors in politics and military. This dynasty instituted imperial tradition in Rome[60] and frustrated any attempt to reestablish Republic.[61]

Augustus

Augustus gathered almost all the republican powers under his official title, princeps: he had powers of consul, princeps senatus, aedile, censor and tribune – including tribunician sacrosanctity.[62] This was the base of an emperor's power. Augustus also styled himself as Imperator Gaius Julius Caesar divi filius, "Commander Gaius Julius Caesar, son of the deified one". With this title he not only boasted his familial link to deified Julius Caesar, but the use of Imperator signified a permanent link to the Roman tradition of victory.He also diminished the Senatorial class influence in politics by boosting the equestrian class. The senators lost their right to rule certain provinces, like Egypt; since the governor of that province was directly nominated by the emperor. The creation of the Praetorian Guard and his reforms in military, setting the number of legions in 28, ensured his total control over the army.[63]

Statue of Augustus, the first Roman emperor.

In military activity, Augustus was absent at battles. His generals were responsible for the field command; gaining much respect from the populace and the legions, such as Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, Nero Claudius Drusus and Germanicus. Augustus intended to extend the Roman Empire to the whole known world, and in his reign, Rome had conquered Cantabria Aquitania, Raetia, Dalmatia, Illyricum and Pannonia.[66]

Under Augustus's reign, Roman literature grew steadily in the Golden Age of Latin Literature. Poets like Vergil, Horace, Ovid and Rufus developed a rich literature, and were close friends of Augustus. Along with Maecenas, he stimulated patriotic poems, as Vergil's epic Aeneid and also historiographical works, like those of Livy. The works of this literary age lasted through Roman times, and are classics.

Augustus also continued the shifts on the calendar promoted by Caesar, and the month of August is named after him.[67] Augustus brought a peaceful and thriving era to Rome, that is known as Pax Augusta or Pax Romana. Augustus died in 14 AD, but the empire’s glory continued after his era.

From Tiberius to Nero

Extent of the Roman Empire under Augustus. The yellow legend represents the extent of the Republic in 31 BC, the shades of green represent gradually conquered territories under the reign of Augustus, and pink areas on the map represent client states; however, areas under Roman control shown here were subject to change even during Augustus' reign, especially in Germania.

The Senate agreed with the succession, and granted to Tiberius the same titles and honors once granted to Augustus: the title of princeps and Pater patriae, and the Civic Crown. However, Tiberius was not an enthusiast of political affairs: after agreement with the Senate, he retired to Capri in 26 AD,[70] and left control of the city of Rome in the hands of the praetorian prefect Sejanus (until 31 AD) and Macro (from 31 to 37 AD). Tiberius was regarded as an evil and melancholic man, who may have ordered the murder of his relatives, the popular general Germanicus in 19 AD,[71] and his own son Drusus Julius Caesar in 23 AD.[71]

Tiberius died (or was killed)[71] in 37 AD. The male line of the Julio-Claudians was limited to Tiberius' nephew Claudius, his grandson Tiberius Gemellus and his grand-nephew Caligula. As Gemellus was still a child, Caligula was chosen to rule the Empire. Being a popular leader in the first half of his reign, Caligula became a crude and insane tyrant in his years controlling government.[72][73] Suetonius states that he committed incest with his sisters, killed some men just for amusement and nominated a horse for a consulship.[74]

The Praetorian Guard murdered Caligula four years after the death of Tiberius,[75] and, with belated support from the senators, proclaimed his uncle Claudius as the new emperor.[76] Claudius was not as authoritarian as Tiberius and Caligula. Claudius conquered Lycia and Thrace; his most important deed was the beginning of the conquest of Britain.[77]

Claudius was poisoned by his wife, Agrippina the Younger in 54 AD.[78] His heir was Nero, son of Agrippina and her former husband, since Claudius' son, Britannicus, had not reached manhood upon his father's death. Nero is widely known as the first persecutor of Christians and for the Great Fire of Rome, rumoured to have been started by the emperor himself.[79][80] Nero faced many revolts during his reign, like the Pisonian conspiracy and the First Jewish-Roman War. Although Nero defeated these rebels, he could not overthrow the revolt led by Servius Sulpicius Galba. The Senate soon declared Nero a public enemy, and he committed suicide.[81]

Flavian dynasty

The Flavians were the second dynasty to rule Rome.[82] In 68 AD, year of Nero's death, there was no chance of return to the old and traditional Roman Republic, thus a new emperor had to rise. After the turmoil in the Year of the Four Emperors, Titus Flavius Vespasianus (anglicized as Vespasian) took control of the Empire and established a new dynasty. Under the Flavians, Rome continued its expansion, and the state remained secure.[83][84]Vespasian

Vespasian was a great general under Claudius and Nero. He fought as a commander in the First Jewish-Roman War along with his son Titus. Following the turmoil of the Year of the Four Emperors – In 69 AD, four emperors were enthroned: Galba, Otho, Vitellius and finally, Vespasian -, he crushed Vitellius' forces and became emperor.[85]He reconstructed many buildings which were uncompleted, like a statue of Apollo and the temple of Divus Claudius ("the deified Claudius"), both initiated by Nero. Buildings once destroyed by the Great Fire of Rome were rebuilt, and he revitalized the Capitol. Vespasian also started the construction of the Flavian Amphitheater, more commonly known as the Colosseum.[86]

The historians Josephus and Pliny the Elder wrote their works during Vespasian's reign. Vespasian was Josephus' sponsor and Pliny dedicated his Naturalis Historia to Titus, son of Vespasian.

Vespasian sent legions to defend the eastern frontier in Cappadocia, extended the occupation in Britain and renewed the tax system. He died in 79 AD.

Titus and Domitian

Titus had a short-lived rule; he was emperor from 79–81 AD. He finished the Flavian Amphitheater, which was constructed with war spoils from the First Jewish-Roman War, and promoted games that lasted for a hundred days. These games were for celebrating the victory over the Jews and included gladiatorial combats, chariot races and a sensational mock naval battle that flooded the grounds of the Colosseum.[87][88]Titus constructed a line of roads and fortifications on the borders of modern-day Germany; and his general Gnaeus Julius Agricola conquered much of Britain, leading the Roman world so far as Scotland. On the other hand, his failed war against Dacia was a humiliating defeat.[89]

Titus died of fever in 81 AD, being succeeded by his brother Domitian. As emperor, Domitian assumed totalitarian characteristics[90] and thought he could be a new Augustus, and tried to make a personal cult of himself.

Domitian ruled for fifteen years, and his reign was marked by his attempts to compare himself to the gods. He constructed at least two temples in honour of Jupiter, the greatest deity in Roman religion. He also liked to be called "Dominus et Deus" ("Master and God").[91] The nobles disliked his rule, and he was murdered by a conspiracy in 96 AD.

Nerva–Antonine dynasty

During the rule of the Nerva–Antonine, Rome reached its territorial and economical apogee.[92] This time was a peaceful one for Rome: the criteria for choosing an emperor were the qualities of the candidate and no longer ties of kinship; additionally there were no civil wars or military defeats in that time.Following Domitian's murder, the Senate rapidly appointed Nerva to hold imperial dignity – this was the first time that senators chose the emperor since Octavian was honored with the titles of princeps and Augustus. Nerva had a noble ancestry, and he served as an advisor to Nero and the Flavians. His rule restored many of the liberties once taken by Domitian[93] and started the last golden era of Rome.

Trajan

Eugène Delacroix. The Justice of Trajan (fragment).

Trajan was greeted by the people of Rome with great enthusiasm, which he justified by governing well and without the bloodiness that had marked Domitian's reign. He freed many people who had been unjustly imprisoned by Domitian and returned a great deal of private property that Domitian had confiscated; a process begun by Nerva before his death.[94]

Trajan conquered Dacia, and defeated the king Decebalus, who had defeated Domitian's forces. In the First Dacian War (101–102), the defeated Dacia became a client kingdom; in the Second Dacian War (105–106), Trajan completely devastated the enemy's resistance and annexed Dacia to the Empire. Trajan also annexed the client state of Nabatea to form the province of Arabia Petraea, which included the lands of southern Syria and northwestern Arabia.[95]

He erected many buildings that still survive to this day, such as Trajan's Forum, Trajan's Market and Trajan's Column. His main architect was Apollodorus of Damascus; Apollodorus made the project of the Forum and of the Column, and also reformed the Pantheon. Trajan's triumphal arches in Ancona and Beneventum are other constructions projected by him. In Dacian War, Apollodorus made a great bridge over the Danube for Trajan.[96]

Trajan's final war was against Parthia. When Parthia appointed a king for Armenia who was unacceptable (Parthia and Rome shared dominance over Armenia) to Rome, he declared war. He probably wanted to be the first Roman leader to conquer Parthia, and repeat the glory of Alexander the Great, conqueror of Asia, whom Trajan next followed in the clash of Greek-Romans and the Persian cultures.[97] In 113 he marched to Armenia and deposed the local king. In 115 Trajan turned south into the core of Parthian hegemony, taking the Northern Mesopotamian cities of Nisibis and Batnae and organizing a province of Mesopotamia in the beginning of 116, when coins were issued announcing that Armenia and Mesopotamia had been put under the authority of the Roman people.[98]

In that same year, he captured Seleucia and the Parthian capital Ctesiphon. After defeating a Parthian revolt and a Jewish revolt, he withdrew due to health issues. In 117, his illness grew and he died of edema. He nominated Hadrian as his heir. Under Trajan's leadership the Roman Empire reached the peak of its territorial expansion; Rome's dominion now spanned 2.5 million square miles (6.5 million km²).[99]

From Hadrian to Commodus

The prosperity brought by Nerva and Trajan continued in the reigns of subsequent emperors, from Hadrian to Marcus Aurelius. Hadrian withdrew all the troops stationed in Parthia and Mesopotamia, abandoning Trajan's conquests. Hadrian's government was very peaceful, since he avoided wars: he constructed fortifications and walls, like the famous Hadrian's Wall between Roman Britain and the barbarians of modern-day Scotland.A famous philhellenist, he promoted culture, specially the Greek culture. He also forbade torture and humanized the laws. Hadrian built many aqueducts, baths, libraries and theaters; additionally, he traveled nearly every single province in the Empire to check the military and infrastructural conditions.[100]

After Hadrian's death at 138, his successor Antoninus Pius built temples, theaters, and mausoleums, promoted the arts and sciences, and bestowed honours and financial rewards upon the teachers of rhetoric and philosophy. Antoninus made few initial changes when he became emperor, leaving intact as far as possible the arrangements instituted by Hadrian. Antoninus expanded the Roman Britain by invading southern Scotland and building the Antonine Wall.[101] He also continued Hadrian's policy of humanizing the laws. He died in 161 AD.

Marcus Aurelius, known as the Philosopher, was the last of the Five Good Emperors. He was a stoic philosopher and wrote a book called Meditations. He defeated barbarian tribes in the Marcomannic Wars as well as the Parthian Empire.[102] His co-emperor, Lucius Verus died in 169 AD, probably victim of the Antonine Plague, a pandemic that swept nearly five million people through the Empire in 165–180 AD.[103]

From Nerva to Marcus Aurelius, the empire achieved an unprecedented happy and glorious status. The powerful influence of laws and manners had gradually cemented the union of the provinces. All the citizens enjoyed and abused the advantages of wealth. The image of a free constitution was preserved with decent reverence. The Roman senate appeared to possess the sovereign authority, and devolved on the emperors all the executive powers of government. The Five Good Emperors’ rule is considered the greatest era of the Empire.[104]

Commodus, son of Marcus Aurelius, became emperor after his father's death. He is not counted in the Five Good Emperors group. Firstly, because he had direct kinship with the latter emperor; in addition, he was not like his predecessors in personality and acts. Commodus usually took part on gladiatorial combats – a symbol of brutality and roughness , since a gladiator was always a slave -, and was a cruel, lewd and narcissistic man. He killed many citizens and his reign is the beginning of Roman decadence, as stated Cassius Dio: "(Rome has transformed) from a kingdom of gold to one of iron and rust".[105]

Severan dynasty

Commodus was killed by a conspiracy involving Quintus Aemilius Laetus and his wife Marcia in late 192 AD. The following year is known as the Year of the Five Emperors. Pertinax, Didius Julianus, Pescennius Niger, Clodius Albinus and Septimius Severus fought for the imperial dignity. After many battles against the other generals, Severus established himself as the new emperor. He and his successors governed with the legions' support – and they paid money for this support. The changes on coinage and military expenditures were the root of the financial crisis that marked the Crisis of the 3rd century.Septimius Severus

Septimius Severus at Glyptothek, Munich

Severus attempted to revive totalitarianism and in an address to people and the Senate, he praised the severity and cruelty of Marius and Sulla, which worried the senators.[108] When Parthia invaded Roman territory, Severus waged war against that country. He seized the cities of Nisibis, Babylon and Seleucia. Reaching Ctesiphon, the Parthian capital, he ordered a great plunder and his army slew and captured many people. Albeit this military success, he failed in invading Hatra, a rich Arabian city. Severus killed his legate, for the latter was gaining respect from the legions; and his soldiers were hit by famine. After this disastrous campaign, he withdrew.[109]

Severus also intended to vanquish the whole of Britain. In order to achieve this, he waged war against the Caledonians. After many casualties in the army due to the terrain and the barbarians' ambushes, Severus went himself to the field. However, he became ill and died in 211 AD.

From Caracalla to Alexander Severus

Upon the death of Severus, his sons Caracalla and Geta were made emperors. Caracalla got rid of his brother in that same year. Like his father, Caracalla was a warlike man. He continued Severus' policy, and gained respect from the legions. Caracalla was a cruel man, and ordered several slayings during his reign. He ordered the death of people of his own circle, like his tutor, Cilo, and a friend of his father, Papinian.Knowing that the citizens of Alexandria disliked him and were speaking ill of his character, he slew almost the entire population of the city. Arriving there, he served a banquet for the notable citizens. After that, his soldiers killed all the guests, and he marched into the city with the army, slaying most of Alexandria's people.[110][111] In 212, he issued the Edict of Caracalla, giving full Roman citizenship to all free men living in the Empire. Caracalla was murdered by one of his soldiers during a campaign in Parthia, in 217 AD.

The Praetorian prefect Macrinus, who ordered Caracalla's murder, assumed power. His brief reign ended in 218, when the youngster Elagabalus, a relative of the Severi, gained support from the legionaries and fought against Macrinus. Elagabalus was an incompetent and lascivious ruler,[112] who was well known for extreme extravagance. Cassius Dio, Herodian and the Historia Augusta have many accounts about his extravagance.

Elagabalus was succeeded by his cousin Alexander Severus. Alexander waged war against many foes, like the revitalized Persia and German peoples who invaded Gaul. His losses made the soldiers dissatisfied with the emperor, and some of them killed him during his German campaign, in 235 AD.[113]

Crisis of the 3rd century

A disastrous scenario emerged after the death of Alexander Severus: the Roman state was plagued by civil wars, external invasions, political chaos, pandemics and economic depression.[114][115] The old Roman values had fallen, and Mithraism and Christianity had begun to spread through the populace. Emperors were no longer men linked with nobility; they usually were born in lower-classes of distant parts of the Empire. These men rose to prominence through military ranks, and became emperors through civil wars.There were 26 emperors in a 49-year period, a signal of political instability. Maximinus Thrax was the first ruler of that time, governing for just three years. Others ruled just for a few months, like Gordian I, Gordian II, Balbinus and Hostilian. The population and the frontiers were abandoned, since the emperors were mostly concerned with defeating rivals and establishing their power.

The economy also suffered during that epoch. The massive military expenditures from the Severi caused a devaluation of Roman coins. Hyperinflation came at this time as well. The Plague of Cyprian broke out in 250 and killed a huge portion of the population.[116]

In 260 AD, the provinces of Syria Palaestina, Asia Minor and Egypt separated from the rest of the Roman state to form the Palmyrene Empire, ruled by Queen Zenobia and centered on Palmyra. In that same year the Gallic Empire was created by Postumus, retaining Britain and Gaul.[117] These countries separated from Rome after the capture of emperor Valerian, who was the first Roman ruler to be captured by enemies; Valerian was captured and executed by the Sassanids of Persia – a humiliating fact for the Romans.[116]

The crisis began to recede during the reigns of Claudius Gothicus (268–270), who defeated the Goths invaders, and Aurelian (271–275), who reconquered both Gallic and Palmyrene Empire[118][119] During the reign of Diocletian, a more competent ruler, the crisis was overcome.

Dominate

Diocletian

In 284 AD, Diocletian was hailed as Imperator by the eastern legions. Diocletian healed the empire from the crisis, by political and economic shifts. A new form of government was established: the Tetrarchy. The Empire was divided among four emperors, two in the West and two in the East. The first tetrarchs were Diocletian (in the East), Maximian (in the West), and two junior emperors, Galerius (in the East) and Flavius Constantius (in the West). To adjust the economy, Diocletian made several tax reforms.[120]Diocletian expelled the Persians who plundered Syria and conquered some barbarian tribes with Maximian. He adopted many behaviors of Eastern monarchs, like wearing pearls and golden sandals and robes. Anyone in presence of the emperor had now to prostrate himself[121] – a common act in the East, but never practiced in Rome before. Diocletian did not use a disguised form of Republic, as the other emperors since Augustus had done.[122]

Diocletian was also responsible for a significant Christian persecution. In 303 he and Galerius started the persecution and ordered the destruction of all the Christian churches and scripts and forbade Christian worship.[123]

Diocletian abdicated in 305 AD together with Maximian, thus, he was the first Roman emperor to resign. His reign ended the traditional form of imperial rule, the Principate (from princeps) and started the Dominate (from Dominus, “Master”)

Constantine and the Christianity

Constantine assumed the empire as a tetrarch in 306. He conducted many wars against the other tetrarchs. Firstly he defeated Maxentius in 312. In 313, he issued the Edict of Milan, which granted liberty for Christians to profess their religion.[124] Constantine was converted to Christianity, enforcing the Christian faith. Therefore, he began the Christianization of the Empire and of Europe – a process concluded by the Catholic Church in the Middle Ages.The Franks and the Alamanni were defeated by him during 306–308. In 324 he defeated another tetrarch, Licinius, and controlled all the empire, as it was before Diocletian. To celebrate his victories and Christianity’s relevance, he rebuilt Byzantium and renamed it Nova Roma (“New Rome”); but the city soon gained the informal name of Constantinople (“City of Constantine”).[125][126] The city served as a new capital for the Empire. In fact, Rome had lost its central importance since the Crisis of the 3rd century – Mediolanum was the capital from 286 to 330, and continued to hold the imperial court of West until the reign of Honorius, when Ravenna was made capital, in the 5th century.[127]

Constantine’s administrative and monetary reforms, reuniting the Empire under one emperor, and rebuilding the city of Byzantium changed the high period of the ancient world.

Fall of the Western Roman Empire

After Constantine’s rule, the empire entered a critical stage which terminated with the fall of the Western Roman Empire.[128] Christianity, corruption, and many other factors have been blamed for its decline.[129]Under the last of the Constantinians and the Valentinian dynasty, Rome lost decisive battles against the Persians and Germanic barbarians: in 363, emperor Julian the Apostate was killed in the Battle of Samarra, against the Persians and the Battle of Adrianople cost the life of emperor Valens (364–378); the victorious Goths were never expelled from the Empire nor assimilated.[130] Theodosius (379–395) gave even more force to the Christian faith; after his death, the Empire was divided into the Eastern Roman Empire, ruled by Arcadius and the Western Roman Empire, commanded by Honorius; both were Theodosius’ sons.

The situation became more critical in 408, after the death of Stilicho, a general who tried to reunite the Empire and repel barbarian invasion in the early years of the 5th century. The professional field army collapsed. In 410, the Theodosian dynasty saw the Visigoths sack Rome.[131] During the 5th century, the Western Empire saw a significant reduction of its territory. The Vandals conquered North Africa, the Visigoths claimed Gaul, Hispania was taken by the Suebi, Britain was abandoned by the central government, and the Empire suffered further from the invasions of Attila, chief of the Huns.[132][133][134][135][136][137]

Finally, general Orestes refused to meet the demands of the barbarian “allies” who now formed the army, and tried to expel them from Italy. Unhappy with this, their chieftain Odoacer defeated and killed Orestes, invaded Ravenna and dethroned Romulus Augustus, son of Orestes. This event happened in 476, and historians usually take it as the mark of the end of Classical Antiquity and beginning of the Middle Ages.[138][139]

After some 1200 years of independence and nearly 700 years as a great power, the rule of Rome in the West ended.[140] The Eastern Empire had a different fate. It survived for almost 1000 years after the fall of its Western counterpart and became the most stable Christian realm during the Middle Ages. During the 6th century, Justinian briefly reconquered Northern Africa and Italy, but Byzantine possessions in the West were reduced to southern Italy and Sicily within a few years after Justinian's death.[141] In the east, partially resulting from the destructive Plague of Justinian, the Byzantines were threatened by the rise of Islam, whose followers rapidly conquered the territories of Syria, Armenia and Egypt during the Byzantine-Arab Wars, and soon presented a direct threat to Constantinople.[142][143] In the following century, the Arabs also captured southern Italy and Sicily.[144] Slavic populations were also able to penetrate deep into the Balkans.

The Byzantines, however, managed to stop further Islamic expansion into their lands during the 8th century and, beginning in the 9th century, reclaimed parts of the conquered lands.[17][145] In 1000 AD, the Eastern Empire was at its height: Basileios II reconquered Bulgaria and Armenia, culture and trade flourished.[146] However, soon after the expansion was abruptly stopped in 1071 with their defeat in the Battle of Manzikert. The aftermath of this important battle sent the empire into a protracted period of decline. Two decades of internal strife and Turkic invasions ultimately paved the way for Emperor Alexius I Comnenus to send a call for help to the Western Europe kingdoms in 1095.[142]

The West responded with the Crusades, eventually resulting in the Sack of Constantinople by participants in the Fourth Crusade. The conquest of Constantinople in 1204 fragmented what remained of the Empire into successor states, the ultimate victor being that of Nicaea.[147] After the recapture of Constantinople by Imperial forces, the Empire was little more than a Greek state confined to the Aegean coast. The Eastern Empire collapsed when Mehmed II conquered Constantinople on 29 May, 1453.[148]

Historians

Main article: Roman historiography

Rome has a very rich history, which was explored by many authors, both ancient and modern. The first history works were written after the First Punic War. Many of these works were made for propaganda of the Roman culture and customs, and also as moral essays. Although the diversity of works, many of them are lost and due to this, there are large gaps in Roman history, which are filled by unreliable works, as the Historia Augusta and books from obscure authors. However, there remain a number of accounts of Roman History.In Roman times

There is a huge variety of historians who lived in Roman times and wrote on Rome. The first historians used their works for lauding of Roman culture and customs. By the end of Republic, some historians distorted their histories to flatter their patrons – this happened on the time of Marius' and Sulla's clash.[149] Caesar wrote his own histories to make a complete account of his military campaigns in Gaul and in the Civil War.In the Empire, the biographies of famous men and early emperors flourished, examples being The Twelve Caesars of Suetonius, and Plutarch's Parallel Lives. Other major works of Imperial times were that of Livy and Tacitus.

- Polybius – The Histories

- Sallust – Bellum Catilinae and Bellum Jugurthinum

- Julius Caesar – De Bello Gallico and De Bello Civili

- Livy – Ab Urbe Condita

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus – Roman Antiquities

- Pliny the Elder – Naturalis Historia

- Josephus – The Jewish War

- Suetonius – The Twelve Caesars (De Vita Caesarum)

- Tacitus – Annales and Histories

- Plutarch – Parallel Lives (a series of biographies of famous Roman and Greek men)

- Cassius Dio – Historia Romana

- Herodian – History of the Roman Empire since Marcus Aurelius

In Modern times

After the Renaissance, Roman history occupied a prominent place in Western culture. A new generation of historians, some with views very different from those of their predecessors, revisited the subject, analyzing life in ancient Rome and discussing what it meant to be a Roman.- Edward Gibbon (1737–1794) — The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

- John Bagnall Bury (1861–1927) – History of the Later Roman Empire

- Michael Grant (1914–2004) — The Roman World[150]

- Barbara Levick (1932– )— Claudius[151]

- Barthold Georg Niebuhr (1776–1831)

- Michael Rostovtzeff (1870–1952)

- Howard Hayes Scullard (1903–1983)— The History of the Roman World[152]

- Ronald Syme (1903–1989)— The Roman Revolution[153]

- Adrian Goldsworhty (1969– ) – Caesar: The Life of a Colossus and How Rome fell[154]

No comments:

Post a Comment